The United Kingdom has resorted to restarting a coal-fired power plant to meet demand for air conditioning after the nation was hit by a major heatwave.

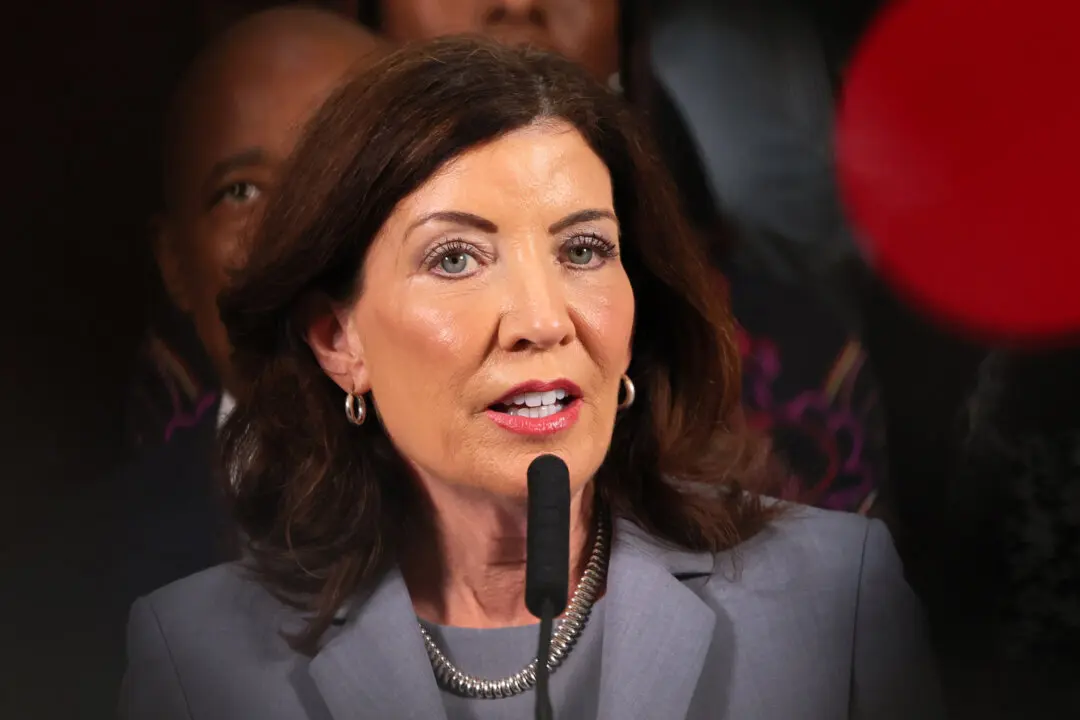

A view of the cooling towers of the Drax coal-fired power station near Selby, northern England, on Sept. 25, 2015. Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images

|Updated: