New UK legislation that aims to stop British people from participating in forced organ harvesting in China has been approved unopposed in Parliament.

The amendment to the UK’s new Health and Care Bill—if it becomes law—will criminalise any UK resident who pays for the supply of an organ, seeks to find someone willing to supply an organ for payment, or initiates or negotiates any such commercial arrangement outside of the UK, according to Health Minister Edward Argar.

The proposed legislation applies to residents in Britain and UK nationals that aren’t residents of Northern Ireland.

The amendment states that UK nationals include British citizens, British overseas territories citizens, British Nationals (Overseas) or British Overseas citizens, British subjects under the British Nationality Act 1981, or British protected people within the meaning of that act.

Moving the amendment in the House of Commons, Argar said the measure, coupled with the Conservative government’s “commitment to work with NHS [National Health Service] Blood and Transplant to make more patients aware of the legal, health, and ethical ramifications of purchasing an organ” would “send an unambiguous signal that complicity in the abuses associated with the overseas organ trade will not be tolerated.”

Commercial dealings in organs for transplantation have already been illegal within the UK.

Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting told MPs that the Labour Party welcomes the change in the legislation.

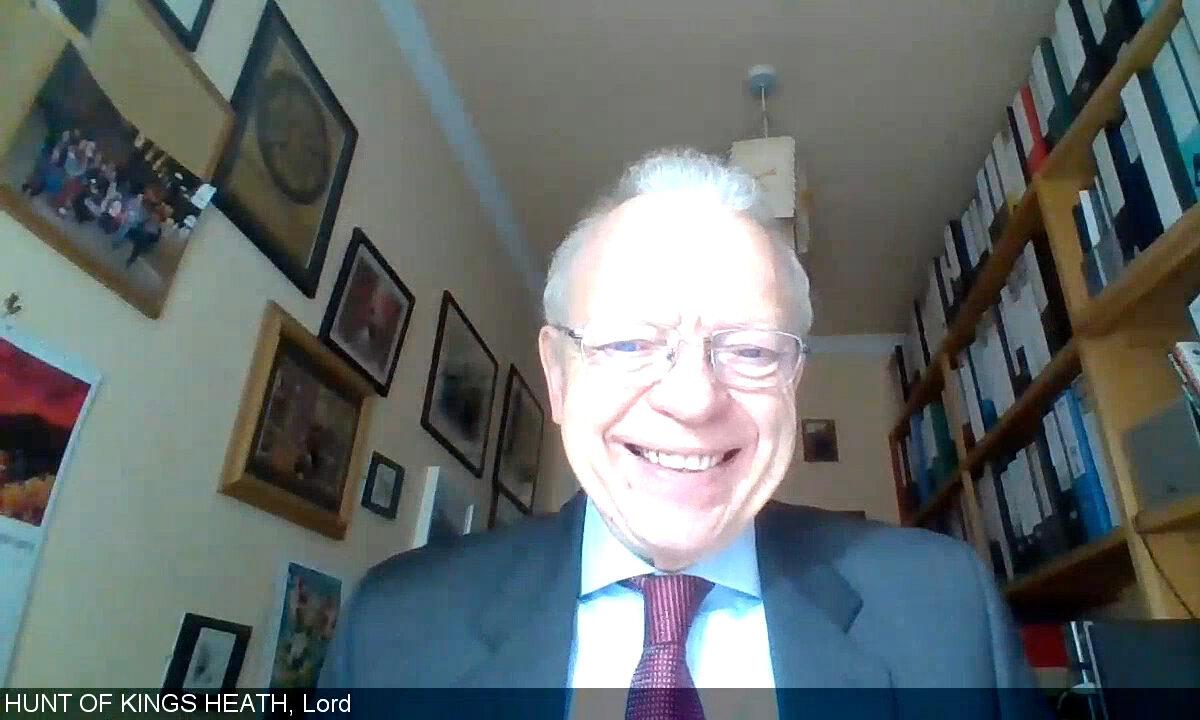

“Forced organ harvesting in China is the crime of forcibly extracting organs from prisoners of conscience, killing the victim in the process. The harvested organs are sold to Chinese officials, Chinese nationals, or foreigners for transplantation,” the Labour peer said.

Stemming from his desire to encourage an increase in organ donations in the UK, Hunt has long campaigned to end forced organ harvesting in China.

Hunt’s amendment, which enjoyed cross-party support in the House of Lords, would also have criminalised receiving organs abroad without “the free, informed, and specific consent” from a living donor or the donor’s next of kin in cases that the donor is unable to provide consent.

It would also have required the health secretary to publish annual assessments of countries that don’t require explicit consent for the legal donation of controlled materials such as human organs.

The proposed assessment report would have determined whether each of those countries provides a formal, publicly funded plan for opting out of deemed consent for donation of controlled materials and effective public education on the system.

The countries would also have been assessed on whether they’re committing genocide by resolution of the House of Commons.

Argar said the government has “significant concerns about the adverse impact this approach—as in that amendment—could have on transport patients and NHS staff.”

The health minister previously told the House of Lords that he believes that by putting the burden on transplant recipients to ensure proper consent is given, Hunt’s amendment would have deterred individuals who “legitimately receive organs overseas” from “seeking follow-up treatment for fear of being treated like a criminal suspect.”

He also said the Hunt amendment would have placed “considerable burdens ”on the NHS by mandating an annual report.

Argar said he believes that his amendment would “achieve a similar effect” to Hunt’s version, “but without creating disproportionate impact on vulnerable recipients and NHS staff.”

In an email to The Epoch Times, Hunt said that he was “absolutely delighted” that the government had accepted the principle of his amendment in outlawing the participation of British people in the “abhorrent practice” of organ tourism.

The Health and Care Bill is currently in the final stage before becoming law—known as the “ping pong,” when the measure goes back and forth between the two Houses of Parliament, each of which considers amendments from the other house.