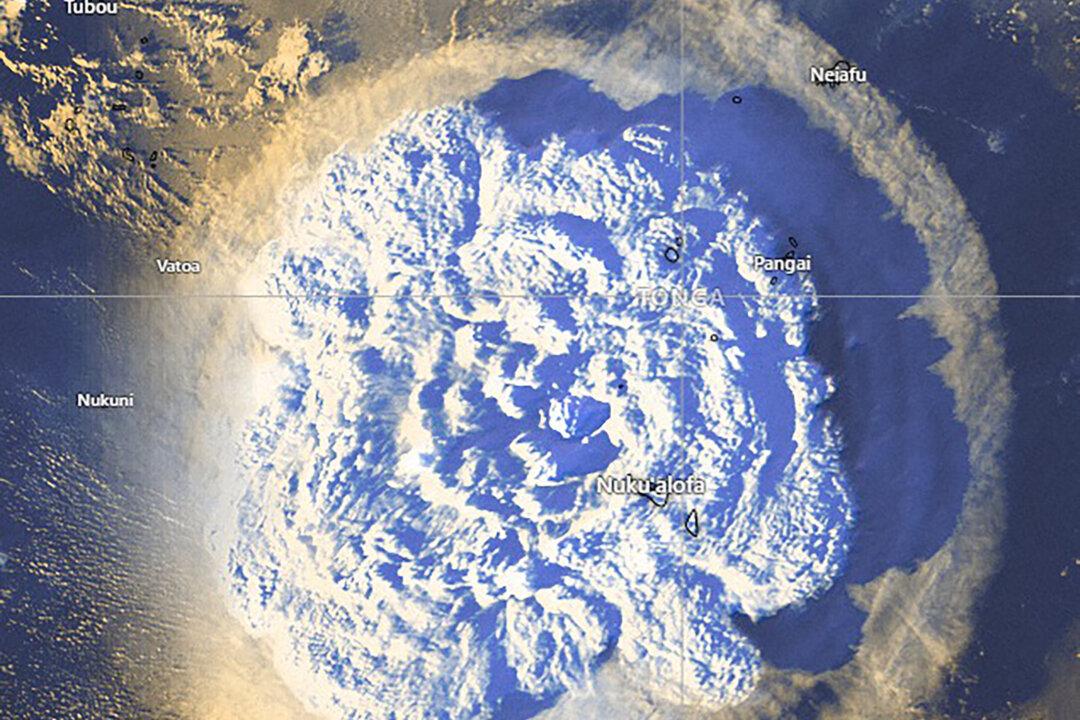

The Tonga volcanic eruption in January was the largest atmospheric explosion documented since the 1883 Krakatoa eruption in Indonesia, according to scientists.

Tonga was hit by an underwater eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano and subsequent tsunami on Jan. 15, which wiped out an entire village on one of Tonga’s small outer islands and killed at least three people.