Commentary

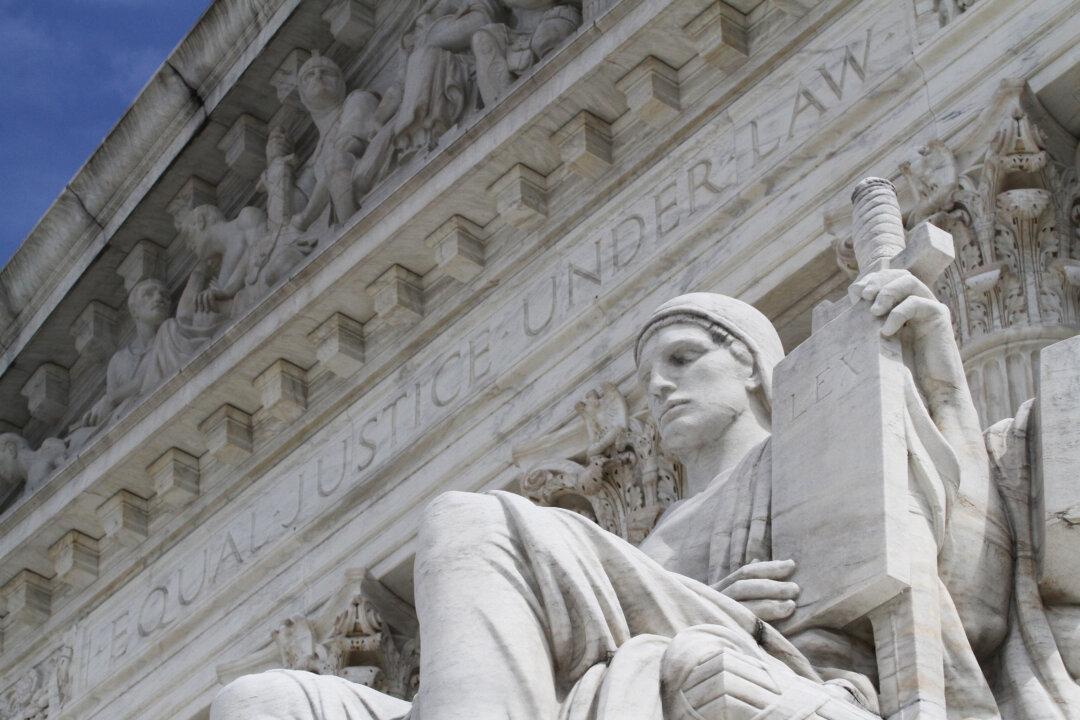

The United States Supreme Court has rendered an important decision on race-based admissions to colleges and universities which, at least indirectly, is relevant to Australia’s debate on the proposed entrenchment of The Voice in the Constitution and necessitates a reflection on Australia’s university admission policies.