Classical ballet has a familiar place in our minds. We know who invented it, the major stars and the eras they pioneered, and the classics of the repertoire—Christmas comes, and so does “The Nutcracker.” We know the five positions of ballet, which from inception to the present day have not changed. Classical Chinese dance, the equally complex system of the East, has a much more complicated provenance. So much so, that even one school in China that claims to have invented it is unclear about where the movements originated.

That school, the Beijing Dance Academy (BDA), officially supported by the Chinese regime, makes the claim to have invented “classical Chinese dance” because it is simply commonly believed. Due to the Academy’s extensive dance curriculum, younger generations of dancers and scholars have mistakenly made that assumption.

But of course, it wasn’t. “What BDA has is a program, a pedagogy, and system of movement that reorganizes classical Chinese dance, and brought it into the academy system. That’s it,” says Guo Hua Ping, a classical Chinese dance instructor in New York.

“How can a modern teaching system suddenly become ‘classical’ with a history of 5,000 years?” Guo says.

To better understand the formation of this art, rooted in a tradition going back 5,000 years, we spoke to experts who have dedicated their lives to preserving the art form.

Training in Opera

Guo Hua Ping, now in her 80s, was born in China in 1935 and grew up in Beijing. Throughout her career, she saw the art form develop, grow in popularity, and morph into something entirely different.

Guo Hua Ping. Copyright Shen Yun Performing Arts

“I must have started [dance] when I was about 13, and I have never done anything else since. What else can you call it but fate?” Guo said.

This was very early communist China, before the Cultural Revolution. Guo remembers, as some of her earliest memories, New Year events at temples, with dances and martial arts performances.

“There were two temples near where I grew up,” Guo said. These were places of reverence for the heavens, great halls established by emperors to pay respects to the divine. During major holidays, they were sites of celebration, where people flocked to pray and burn incense to the gods and watch performances.

“There were Peking Opera performance groups, and they would put on shows—the costumes, acting, dancing, props, the various movements of Peking opera. It was all there,” Guo said. “I was very young, and I loved it. I’d go home and copy what I’d seen, just for play.”

She would later understand that these glimpses of Peking Opera she’d seen were the real deal, a long-standing traditional performing art that had been passed down and developed through the ages.

“This was actually Chinese dance,” she said; it became an important reference point for her later. Chinese dance came from the dances of more than 300 kinds of traditional Chinese operas, such as Kunqu Opera and Peking Opera. These are the main sources of classical Chinese dance.

Guo ended up joining a performing arts military institute, which at one point was named the Zhongnan Theater Company when the state started recruiting little troopers and they saw that she showed talent in the little skits and plays at school.

There, the students learned from Peking Opera experts, like those who’d studied with Mei Lanfang, the famous artist who was the first to spread Chinese opera outside of China. Students might go on to specialize in various things or various roles, but Chinese opera was the fundamental basis for all of it, and everyone took these classes.

As Guo explained, you didn’t start with a separate theory or a technique course on vocal training or footwork; these were entire stories passed via demonstration from teachers to students. The teachers would take scenes from well-known operas and teach them in their entirety—the steps, the staging, the gestures, the songs, even how to warm up—to every class. The experts themselves came from theatrical troupes that typically had a sort of apprenticeship system, with one principal dancer leading a number of students.

“Like the art troupe I was in at the time, many dance professional groups all over the country were learning and arranging dance styles and techniques from traditional operas such as Peking Opera and Kunqu Opera, which were generally referred to as ‘classical Chinese dance,'” Guo said.

Guo took a short moment to demonstrate—a distinct turn of the head, the way the fingers were placed and hands moved, the inflection in tone. “Everybody knew this,” she said, describing several fundamental steps with their names. Guo recalled in the same breath how different types of new characters took to the stage with an introduction, and how different props like twin swords were used. She described an opera scene in particular, which was taught to early classes, depicting a young lady consoling an emperor with a song. This was a systematic art form with a developed vocabulary of movement and an established repertoire.

A few years after Guo started studying at the institute, the Beijing Dance School, later renamed the Beijing Dance Academy (BDA), was formed by the state in 1954. This school began one of the biggest changes to Chinese dance itself.

The formation of the school included first interviewing many Peking Opera experts to decide how to best teach Chinese dance systematically. Then dance teachers from the Soviet Union were invited to lead the classes, which introduced another layer of changes to what was known as Chinese dance.

“Dancers from the Soviet Union … created a Chinese-Ballet hybrid sort of form,” Guo said.

The Ballet Hybrid

The communist states of China and the Soviet Union had good relations at the time, and so even though China had not yet begun to “open up” to the world, the state invited many Soviet Union dance experts to serve as instructors.Guo explained how BDA used ballet pedagogy from the beginning. With the help of Soviet ballet experts and ballet teaching systems, they sought to reorganize classical Chinese dance, drawing from Chinese opera dance with a corresponding teaching system.

It was impossible for the instructors to pick up, much less be able to teach, something developed over thousands of years in full. As the language of ballet was introduced, certain elements automatically disappeared from the vocabulary—most obviously, tumbling techniques like midair somersaults or flying backward flips.

Shen Yun dancer Kaidi Wu performs an aerial, during New Tang Dynasty Television’s 2016 International Classical Chinese Dance Competition. Tumbling elements such as this disappeared when ballet became incorporated into classical Chinese dance training. Larry Dai

There were more fundamental things lost in this use of foreign pedagogy because the character of each dance form is different, to begin with.

“There are many differences … Traditional Chinese dance has explosive starts and a sort of circular way of moving, rounded movements,” said Vina Lee, a classical Chinese dance instructor who grew up training in this period of the Chinese-Ballet hybrid form. At the time, it was so mixed that she would not have known which parts were drawn from ballet and which were from traditional Chinese dance.

Vina Lee. Copyright Shen Yun Performing Arts

Lee, now president of Fei Tian College in upstate New York, said upfront that it was probably not until she came to the States that she started to understand classical Chinese dance, even though she was a ballet instructor for many years before that.

Though this Chinese-Ballet hybrid dominated the scene for a few decades before it gave way to other forms, its introduction played a significant role in the loss of classical Chinese dance.

“Because Beijing [Dance Academy] was using this Chinese-Ballet hybrid, the whole country fell in line and replicated it as well. They put dancers on pointe,” she said.

“But, to use ballet to express Chinese things, it actually doesn’t work. You’re using a Western language to convey the content of another culture,” Lee said. Think about how difficult it is to properly translate an idiom and retain its meaning, for instance, and multiply that many times over.

Translation between languages for everyday things might be a simple task, but this is art and art with deep cultural roots. The East has no concept of the “Pietà,” for instance, and the West is not immediately familiar with the idea of spiritual cultivation.

There are fundamental divides between the East and West. The East has no concept of a "Pietà," for example, and the West no clear model for self-cultivation. Michelangelo's "Pietà" housed in St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. CC-BY-SA 3.0

“Each gesture, every turn of the head, every look—they’re distinctly cultural.” She demonstrates, just in little things like the angle of the head, or how to hold your arms or the placement of the fingers. The difference is stark and immediate. Tiny changes made to every step along the way can add up to quite a lot. “Or, if your upper body is Chinese dance but your feet are on pointe, what does that convey?”

“It’s not that ballet isn’t beautiful or complete, but it’s an entirely different form,” Lee said. “Ballet is about beautiful, long lines and clean leaps and landings. How do you mix that? And the [Chinese Communist Party-approved] Revolutionary Ballets had a very strong propagandistic message, not quite compatible with classical ballet either.”

But the biggest detriment to the development of Chinese dance was not that it mixed in a few ballet moves. It was that it removed tradition from the equation and opened the doors for further hybridization writ large. Traditional Chinese dance, which largely came from Chinese opera, with roots in the imperial courts of ancient dynasties, had never been passed along and taught on a massive, national scale. Not like the Chinese-Ballet hybrid was. In just a few years, people forgot or were forced to forget the significance of the movements and stories passed down via Chinese opera, and things that are not meaningful are later easily removed.

The Revolution

China and the Soviet Union eventually parted ways; the experts left, and the Cultural Revolution took place shortly thereafter.“You either followed the [Chinese Communist] Party or you were sent off to work in the camps,” Lee said, understating the bloody violence of the period. “So there was a break in artistic development for a period of time.”

This poster, displayed in late 1966 in Beijing, shows Red Guards how to deal with a so-called enemy of the people during the Cultural Revolution. During this bloody time, art was used to re-educate people. Jean Vincent/AFP/Getty Images

During this period, there was just what was called the “Eight Model Plays.” This set of operas and ballets was engineered by communist leader Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, and they were meant to glorify the communist revolution and usher in Mao’s cult of personality.

Guo, who had been dancing all of her life, said no one dared to perform any other operas during that time. Mao wanted to replace the old with his own new; even Confucius was thrown out. Who would dare try to develop content in that direction?

“What could we perform?” She demonstrated a few abrupt movements, the kind a child might come up with in jest to mock Hitler or Stalin in a march, and then made a face. If you look up “Red Detachment of Women,” the best-known ballet of the bunch today, it does actually look like that. Violent Marxist themes communicated through the elegant, etiquette-driven classical ballet is more or less a Frankenstein creature of dance.

After the Cultural Revolution, institutes across the nation were replaced by various performing arts troupes, many of which changed names several times as district lines were redrawn. There were still ballet schools, Guo said, but there was nothing called “traditional Chinese dance” or “classical Chinese dance.” Various elements of traditional Chinese dance, like the tumbling techniques or impressive kicks, were used by anyone and every one however they wished, notably in gymnastics and acrobatics competitions. Dance was a mixed bag with little philosophy behind it, except perhaps to dazzle and impress and draw in any audience one could. There was no other way for an artist to make a living in a society that had done away with culture.

“It was a very messy period,” Guo said. “The worst of it was probably that Chinese people could no longer recognize in the arts what aspects were Chinese. We couldn’t recognize our own tradition.”

Rediscovering Chinese Culture

Lee remembers that she had never been particularly proud to be Chinese until she started learning classical Chinese dance and, by extension, traditional Chinese culture.I had to realize what the culture was all about.

“I’d previously not understood, and frankly wasn’t interested in, Chinese arts. I didn’t know how to appreciate them,” Lee said. “I had to realize what the culture was all about.”

She described it as a learning process going back to the fundamentals, of both mind and body.

Just as ballet has, over the centuries, been an expression of various Western cultures, classical Chinese dance can be well understood as the expression of traditional Chinese culture through aesthetic movement.

We need to take into account the timeline: This is civilization stretching back 5,000 years, with formative cultural figures like Confucius and Laotzu being near-contemporaries of Socrates, considered the father of philosophy in the West—two civilizations ago. And it has only been less than a century since the communist takeover of China swung a cleaver down to break the long line of continuous tradition.

“Laotzu Riding an Ox,” Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), by Zhang Lu. National Palace Museum. Public Domain

So what is traditional Chinese culture about? At its very foundation is the idea of harmony between heaven and earth, and reverence for the divine. It is said to be “divinely inspired,” because ancient Chinese people believed that life itself was given by the divine, along with most aspects of Chinese culture.

Before the first dynasty was established, there were the Three Sovereigns or demigods: Suiren, who invented fire; Fuxi, who invented hunting and fishing; and Shennong, the inventor of agriculture. Then there were the early emperors, who were believed to either have divine capabilities or could communicate with divine beings. Everything from the written language to the clothing and the way emperors ruled had some connection, an explicit connection, to the divine.

In writings by scholars and historians spanning millennia, there are constant mentions of the divine and of living virtuously, in accordance with heaven, so that people might receive blessings from the gods. The lessons of history across the numerous dynasties are understood to be distilled into the five cardinal virtues of benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and faithfulness. Inextricable from the culture are also the three religions of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism.

Lee goes on to explain that this value system is one important component of understanding what classical Chinese dance is, in part, because knowing this, one begins to see the reason one moves this way or that way to convey an idea or feeling. Classical Chinese dance is typically a storytelling art form, and in order to portray or understand great historical figures like Emperor Kangxi, General Yue Fei, or the poet Li Bai, you must understand the cultural context of their stories. If you take the culture out of Chinese dance, it really isn’t Chinese dance.

Tony Xue's dance performance "Junior Han Xin," an homage to the great historical Chinese general, earned him a share of first prize in the Junior Male division of New Tang Dynasty Television’s 2009 International Classical Chinese Dance Competition. Edward Dai/ The Epoch Times

Finding the Movements

With the communist campaigns having left China’s traditional culture in ruins, there has been little for artists to rely on, even if they wish to piece together something authentic.But if you understand the traditional culture, according to these dancers, you already have a great many of the pieces with which to build something original yet traditional.

There are clear ideals of femininity and masculinity, for example, Lee said, and it’s not hard to tell whether your dance expresses that. You also start to understand what traditional Chinese art is about and can see when there is a piece that doesn’t quite fit; a previously foreign language becomes easier to decipher.

“With traditional Chinese culture, in the art, a lot of it comes from a clear and calm place of mind. A sort of peace that is precisely an oasis in our busy, modern-day lives,” Lee said.

Having the foundational understanding of traditional Chinese culture becomes useful in recognizing the technique and system of movements inherent in the dance form as well.

Many of the movements look similar to martial arts, for instance, which developed in parallel to the aesthetic art of dance over the 5,000 years. Lee points out that in Chinese, the two words share a homophone. Martial arts is “wushu,” and dance is “wudao,” though the “wu” character is written differently for each.

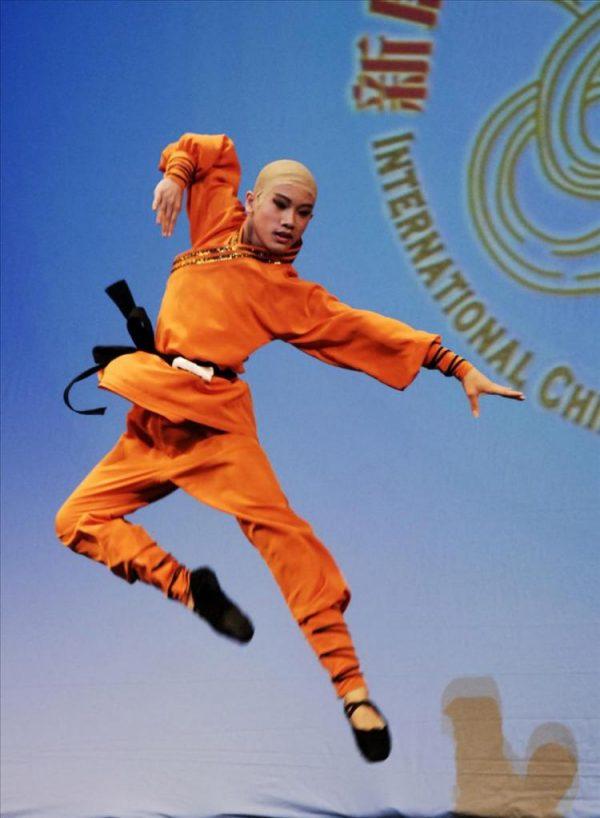

One of the contestants in NTDTV's International Classical Chinese Dance Competition. Dai Bing/The Epoch Times

These forms, in fact, share many movements. Lee demonstrates a punch, and then again with a quicker start and softer ending and turn of her hand to finish. “You beautify the movements when using them in dance,” she said.

Classical Chinese dance movements had been passed down through imperial courts and regional opera productions over thousands of years before they were whittled away piece by piece after the end of the last dynasty. But martial arts movements were not affected in the same way.

Even when martial arts fell in popularity, or when they lost their spiritual component, the movements and sets of movements did not change, and those old martial arts practitioners in the mountains still passed them down.

“You can’t change the movements because they’re functional,” Lee said. “If you change it, it’s not effective anymore.” If someone strikes at you, you still have to dodge. There is obviously a better or worse way to use a spear or a sword. There is no making it up as you go on the battlefield.

Thus, a lot of the movements and also how they combine has been retained, and many see it as a blessing.

These movements retained in martial arts, along with the way of moving drawn from Chinese opera, create a very vivid language.

The movements themselves, along with a systematic approach of how these movements should be linked together—drawn from the long legacy of dance and opera—create a very vivid language.

As the experts explain it, classical Chinese dance is so expressive because it’s the meaning behind a movement that drives the body into movement.

This is referred to as “yun,” or the bearing of the dancer, who may be embodying a specific emperor or hero from a legend, or a character less specific, like a scholar from the Tang Dynasty, or a princess in the Manchurian court.

Culture’s Impact

This is why technique is not enough. You can be a dancer with the highest kicks and most impressive leaps, but if you don’t have the vocabulary—the method of movement, the cultural understanding—when you get on stage, you can’t convincingly portray anyone.

Dress rehearsal at Fei Tian College Middletown, the only college in the nation that offers classical Chinese dance BFA and MFA degrees alongside degrees in classical ballet. Fei Tian College Middletown

“When you fully understand classical Chinese dance, it’s like, ‘Oh! It is a rich and complex language of its own,'” Lee said.

If you speak to classical Chinese dancers today, Lee included, many explain the creative process of learning classical Chinese dance to that of learning what it means to be human. This is partly because as a performing artist, one often serves as a translator of the depth and brilliance of human experience. Just as classical musicians are interpreting for listeners the scores of long gone but genius composers, classical Chinese dancers are actually interpreting the divinely inspired culture and history of ancient China.

“These stories all have cultural context,” Lee said. “If you don’t understand purity and calmness, you can’t express it.”

“To learn classical Chinese dance, you need to have that moral and cultural foundation—that’s why people feel it’s beautiful,” Lee said. She often hears from audiences that it’s so beautiful, but they’re grasping for the how, or why they feel that almost ethereal calm.

It’s because these artists pursue the beauty of a transcendent nature, as in beauty, truth, and goodness. It only takes a twist of the gaze or slight turn of the body to turn that beauty into that of the mere sensory sort—from something sincere into something ironic, or worse, vulgar.

“It stems from your mindset,” Lee reiterates. Your intention drives your movement, and through such a rich and expressive language, the audience is sure to understand what you have conveyed. Though the form itself is not boundless, it can convey boundless things, Lee said.

This is the type of expression where your soul is on display.

Turning Toward Tradition

Guo, who is the principal of the Fei Tian Academy of the Arts, and Lee have both been company managers for Shen Yun Performing Arts, the New York-based company that put classical Chinese dance on the map.Some schools in China, lacking the understanding of traditional culture, have tried to cobble together movements and styles much less successfully. Those who have worked with Shen Yun recognize that it’s become the top classical Chinese dance company internationally, but they say it’s not because that has been the goal.

These traditions of 5,000 years, they’re very precious, meant to be treasured.

“These traditions of 5,000 years, they’re very precious, meant to be treasured,” Guo said. “Tradition cannot be separated from our responsibility. Every one of us [artists] has a responsibility.”

“We’re returning toward tradition and traditional values—this isn’t easy. Even the value system here is different, so everything we express [compared to other schools] looks different. Whether it’s Han Xin, or Yue Fei, or Wu Song, how can you express these figures with modern sensibilities? They’d be unrecognizable,” she said. “And what are you trying to give the audience? Something of meaning, of value … We’re not here to sell tickets, but to give the audience the best things, the best of human culture, wisdom, and relationships.”

Although there is no “classical repertoire” as pertains to classical Chinese dance, and perhaps the pedagogy has been reinvented by various schools in the last few decades, the gestures, system of movements, technique, stories, and expressive soul of the art form are things borne of 5,000 years of divinely inspired civilization.

Those who pursue classical Chinese dance today aren’t in search of “historically informed performances,” but seek to reconnect deeply with a culture that was violently stripped away from the Chinese people less than a hundred years ago. The developments in Chinese dance that Guo has seen over her life are, in reality, developments dictated by the state or a result of the state’s Marxist ideology push, and not at all organic changes driven by artists. Until today, that is.