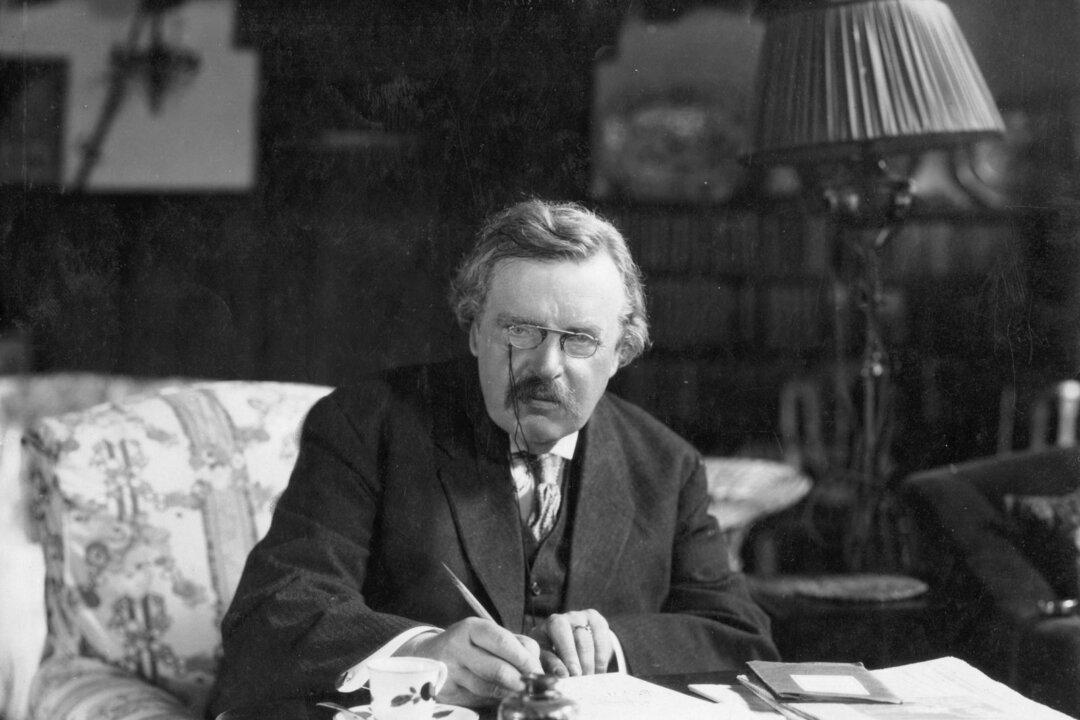

A “bard,” goes the standard definition, is a “declaimer of heroic or epic verse.” Once a tradition in every culture (think Homer), the bard has all but disappeared. The last to write in English was a rotund, bespectacled Londoner, widely known in his time and deserving of greater recognition today.

G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) enjoyed a fabled career in journalism. It was for witty and incisive columns in the Illustrated London News that he was primarily known, along with some fiction, in particular the Father Brown detective stories. Along the way, Chesterton also managed to pen several volumes of Catholic apologetics, including an urgent plea for religious conservatism in his book-length essay, “Orthodoxy,” and perhaps the finest lay consideration of Saint Thomas Aquinas ever written in English.