Commentary

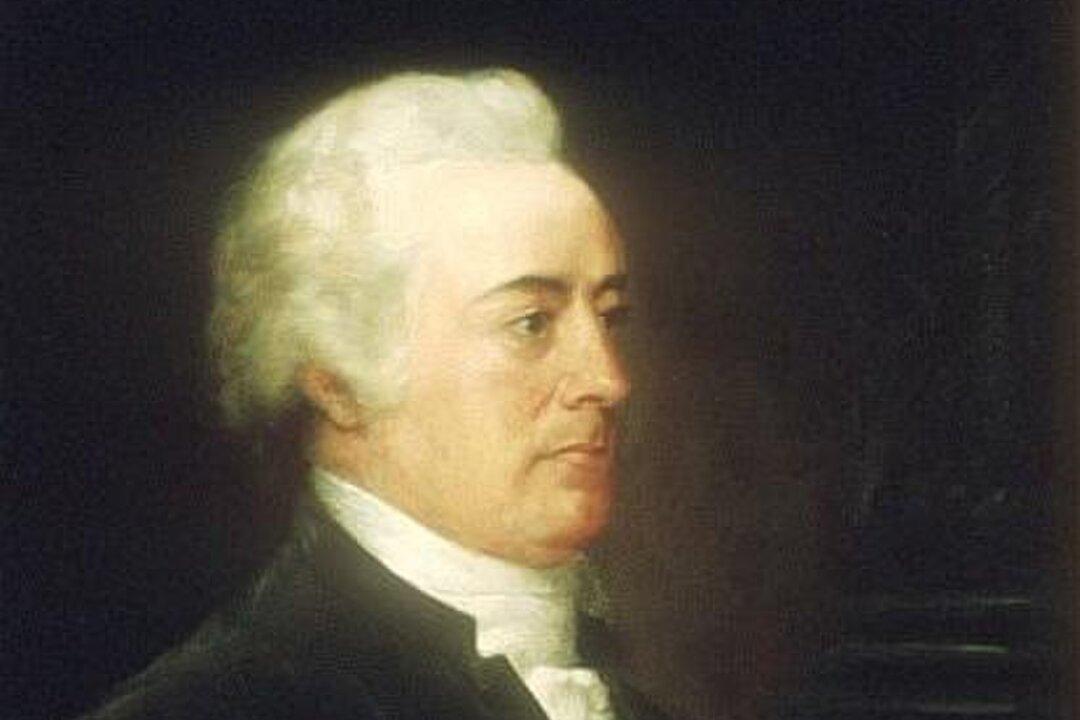

Let’s get the bad news out of the way first: John Rutledge owned slaves. Moreover, during the Constitutional Convention, he informed his fellow delegates that the three southernmost states would not join the Union if the Constitution immediately abolished the slave trade.