Commentary

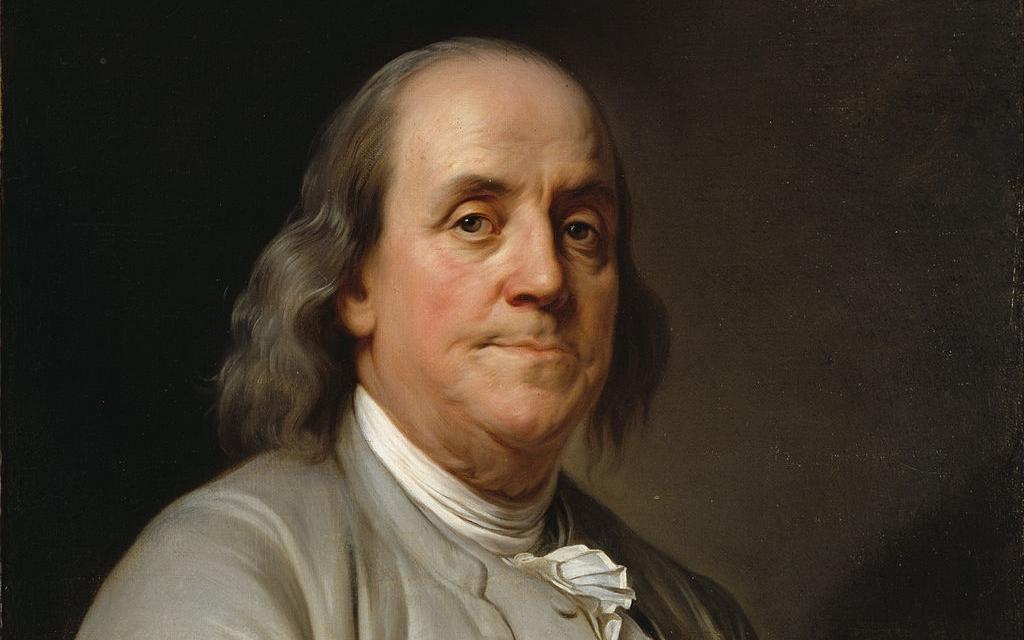

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston on Jan. 6, 1706, the youngest son among a tradesman’s 15 children by two successive wives. He had two years of formal education. At the age of 12, he was apprenticed to his older brother James, a printer. Five years later, he ran away to New York. He couldn’t find a job there. He was forced to travel on to Philadelphia, arriving with one Dutch dollar and about 20 pence in copper.