You have been pleased to send unto us a certain prohibition or command that we should not receive or entertain any of those people called Quakers because they are supposed to be, by some, seducers of the people. For our part we cannot condemn them in this case, neither can we stretch out our hands against them…We desire therefore in this case not to judge lest we be judged, neither to condemn lest we be condemned, but rather let every man stand or fall to his own Master. We are bound by the law to do good unto all men, especially to those of the household of faith.”

With those words, Edward Hart, the town clerk of what is now the Queens neighborhood of Flushing, New York, began a powerful 650-word document known as the Flushing Remonstrance. It was December 27, 1657. Hart wrote on behalf of the 30 inhabitants of the village who also boldly signed their name below his.

The Flushing Remonstrance: The Religious Magna Carta of the New World

A governor demanded religious persecution of the Quakers. The citizens of Flushing refused.

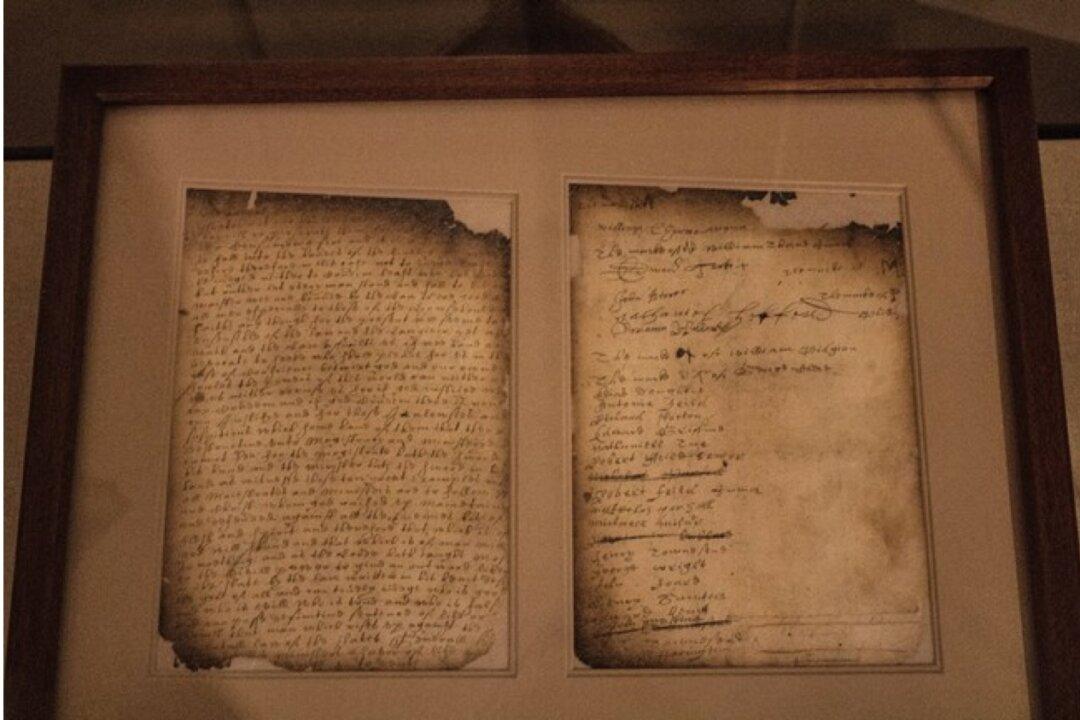

The original Flushing Remonstrance. It sustained damage from a fire at the New York State Capitol in Albany in 1911. NPS

|Updated: