Commentary

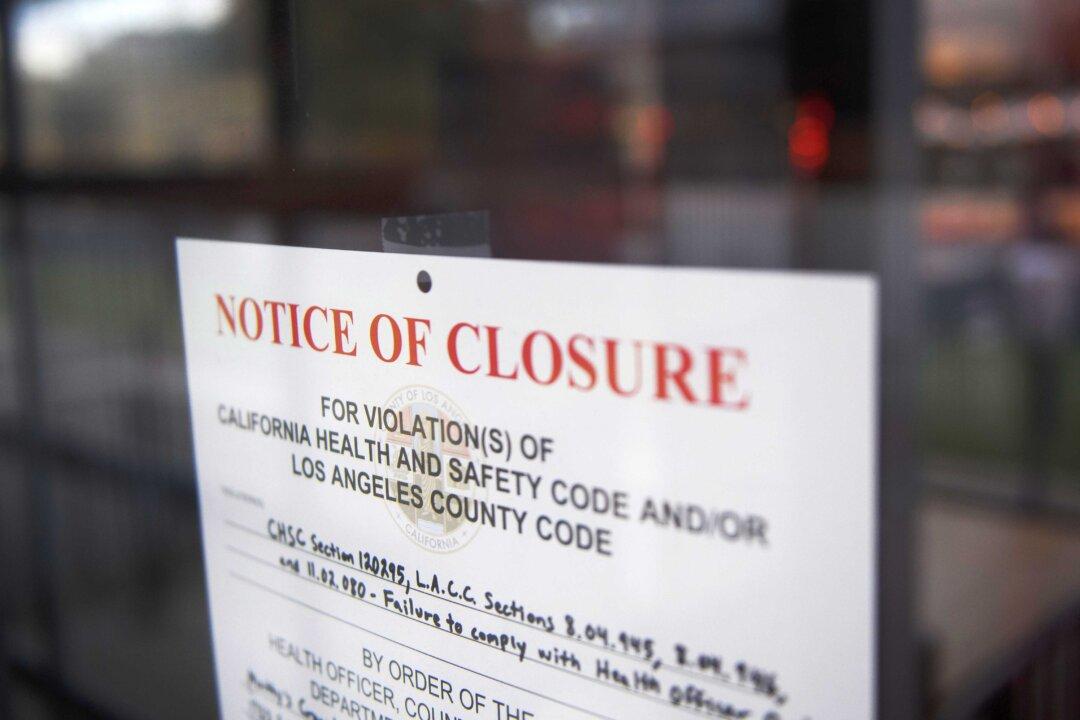

A County of Los Angeles Department of Public Health "Notice of Closure" sign hangs on the door of a restaurant closed due to violations including "failure to comply with health officer order" amid increased Covid-19 restrictions on businesses, in Redondo Beach, Calif., on Jan. 22, 2021. Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

|Updated:

Jeffrey A. Tucker is the founder and president of the Brownstone Institute and the author of many thousands of articles in the scholarly and popular press, as well as 10 books in five languages, most recently “Liberty or Lockdown.” He is also the editor of “The Best of Ludwig von Mises.” He writes a daily column on economics for The Epoch Times and speaks widely on the topics of economics, technology, social philosophy, and culture. He can be reached at [email protected]

Author’s Selected Articles