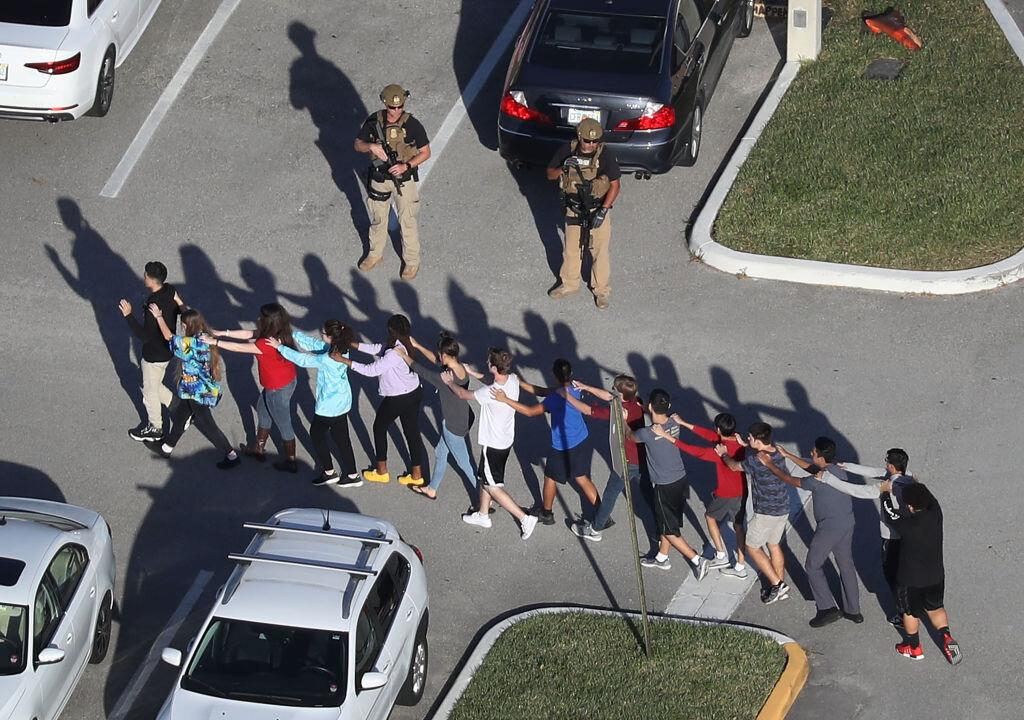

Although not the most costly mass shooting in terms of lives lost, the killing of 17 students in Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on Feb. 13 has unleashed an unprecedented “I’m mad as hell and not going to take this anymore” reaction.

Poignant scenes and finger pointing have dominated the national media, coupled with commitments on various political and social levels to “do something.”