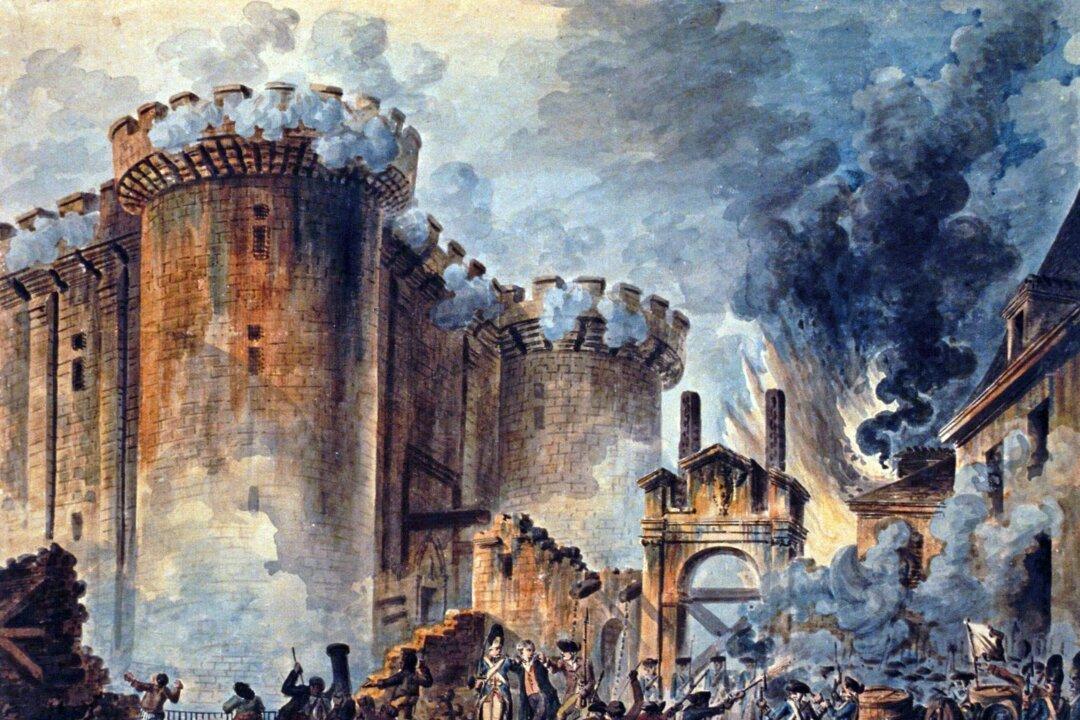

If you were to ask most people about the origins of communism, they‘d likely point to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, authors of “The Communist Manifesto.” If you asked a Marxist, however, they’d likely point to François-Noël “Gracchus” Babeuf, who is regarded as the first revolutionary communist.

And if Babeuf could still speak today and was asked about the origins of his belief, he'd likely reply that, well, it’s complicated.