A collaboration from scientists from Australia and the Netherlands has resulted in a fascinating new study showing immune-boosting benefits of a tuberculosis vaccine.

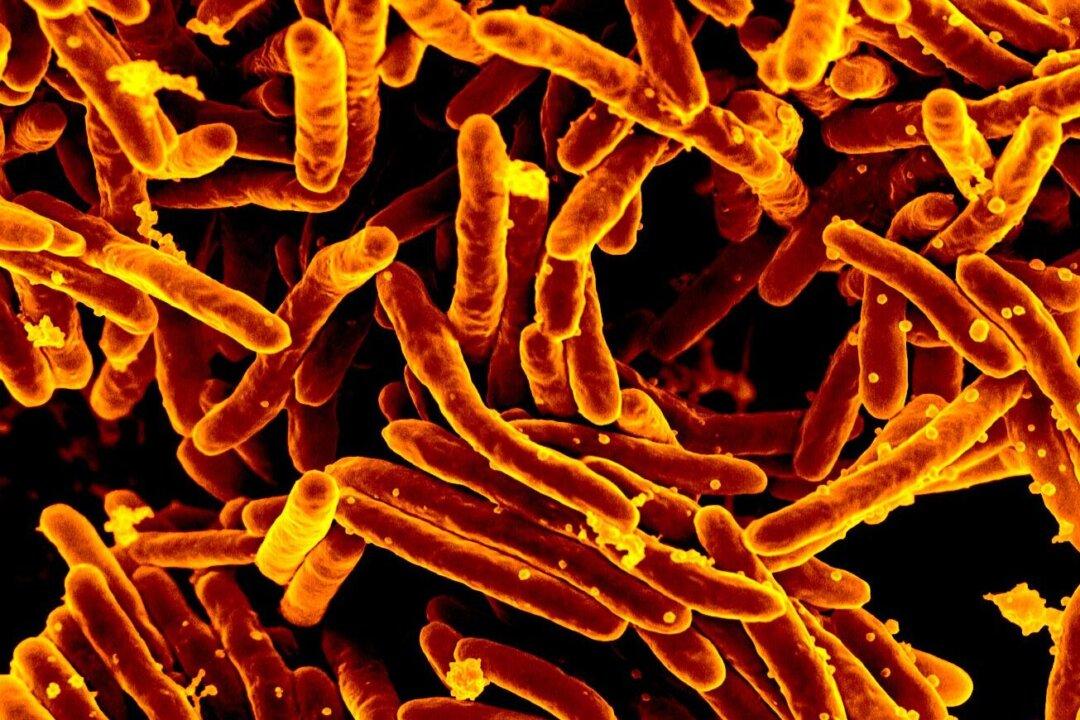

Tuberculosis (TB), or consumption as it was known in 19th century America, is an infectious disease that invades the lungs. Caused by a bacterium, “tubercule baccilum,” TB is spread through droplets in the air via coughing and sneezing.

Once a widespread and deadly disease in America, TB now infects fewer than 8,000 people a year in the United States. In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded 526 deaths from TB.

At the same time, however, TB plagues people in other countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 10 million people contracted it in 2020: 5.6 million men, 3.3 million women, and 1.1 million children.

Some 1.5 million people died. “TB is present in all countries and age groups,” the WHO explains on their site. “But TB is curable and preventable.”

New Vaccine Research

The new study, conducted by scientists from Australia’s Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the Radboud Center for Infectious Diseases in the Netherlands, involved a randomized sample of 130 infants.

Sixty-three of the infants were vaccinated with the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine. BCG, named after its inventors, is made from an attenuated, or weakened, strain of the bacteria that cause TB. It is thought to protect against the most severe forms of TB, including TB meningitis.

The infants given the BCG vaccine were matched with 67 controls who did not receive it.

The researchers found something unexpected: administering the BCG vaccine appeared to provide protection against more than just TB.