Auntie May arrived at Sydney International Airport in 2012, her life was packed neatly into a single suitcase. With clothes borrowed from a cousin and a poor grasp of English, she crossed the threshold and began a new life in Australia.

Deep down, May knew her journey “Down Under” was not for a quiet retirement. Instead, she was preparing for a new lease on life, and a chance to help Chinese people understand the true nature of the Communist Party she suffered under for 60 years.

Born Yuelan Tao in 1956, May’s life began just seven years after China fell under the tyrannical rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Her father was a small business owner and the family lived in Beijing.

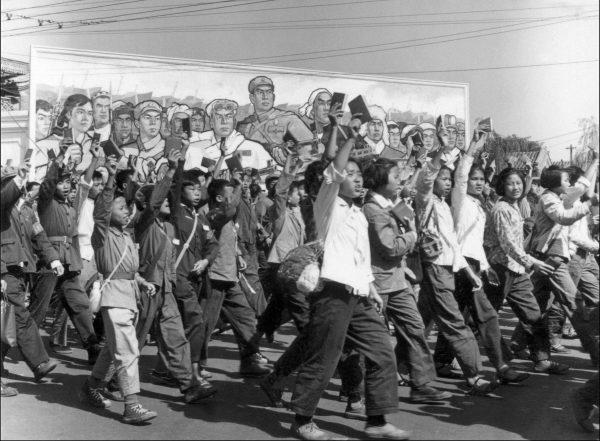

In 1966, her family was swept up in the regime’s Cultural Revolution—a destructive ten-year-long political movement aimed at purging China of its 5,000-year cultural roots.

12 Years as a Slave

Despite owning no land, May’s father was branded a “landlord.” As a result, her family were disenfranchised and expelled to the countryside for 12 years. Her two sisters were spared this fate as they had married into other families.Members of these classes were labelled enemies of the revolution and were disenfranchised, humiliated, and sometimes tortured and killed.

May’s family spent the next decade in a rural commune, earning points within the commune system to exchange for basic food and provisions.

“During those 12 years, I worked so hard that I never dared complain about being tired,” May recalls. “There was nothing in the family that I didn’t take care of.”

“We had nothing. We had no home, money or land, it all belonged to the state,” she added.

Public communes were experiments by the regime to organise families into large collective societal units—working together on farms and growing crops for the nation.

In the communes, livestock, utensils, kitchenware, and ingredients were all shared. Meals were provided and shared amongst everyone.

However, it was barely enough to survive. In some communes, the rationing of food became a “weapon” to force people to follow the Party’s direction.

For May’s family, earning points was initially difficult as they had arrived at the tail-end of the farming season when work was scarce.

“We had no points, so we were not given food for the next year. We had to ask the vegetable seller to lend us food. They recorded our family’s details and would deduct points from us later.”

“There were some kind-hearted people who helped us. They were afraid of speaking to us directly (because her father was labelled a ‘landlord’) so they would throw vegetables through our window.”

In those years, hunger was a constant companion. May says: “At the time I developed a habit of drinking a lot of water. Because there was not enough food and I had to drink, so I was not as hungry.”

“I would often go to harvested farmlands to find leftover corn and wheatears. After bringing it home, my mum would crush and boil it with vegetables. We lived an entire year eating like this,” she says.

Dikotter wrote that as food became scarce, the Red Guards would resort to “coercion and violence” to force workers to keep labouring on agricultural projects.

“The communist leaders and the Red Guard were thugs. My family’s life was destroyed this way,” May says.

Despite the atrocities she endured, something about May strikes me. She seems calm and measured, recalling her experience without breaking down. I ask her why. Many Chinese people took their own lives during the revolution.

Finding Solace in China’s Renaissance

Public communes failed spectacularly, resulting in millions of deaths from starvation caused by a lack of food due to inefficient farming practices.As the Cultural Revolution wound down, May’s family were finally allowed to return to the city in 1978.

May eventually married and worked in a textile factory. However, years of malnutrition had taken its toll. Her body was in poor condition; she had gallbladder issues, chronic fatigue, and suffered regular back pain.

“I was uncomfortable every day and night,” she recalls.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the communist regime started to promote in society a health and wellness practice known as qigong (chi-gong) in an attempt to cope with the rising health care needs of the burgeoning population.

Akin to Tai Chi, qigong practices had once flourished around China with regions and families often handing down their traditions for centuries.

During this period of her life, one practice caught May’s attention: Falun Gong.

Falun Gong was a qigong practice steeped in the Buddhist tradition and growing in popularity around the country. During the early 1990s, Falun Gong garnered millions of followers.

For May, it was like “a renaissance for the Chinese people,” she says.

Within a month of doing Falun Gong’s meditation exercises, strength returned to May’s body and her health improved.

‘Eight Years in Prison Because I Wanted To Meditate’

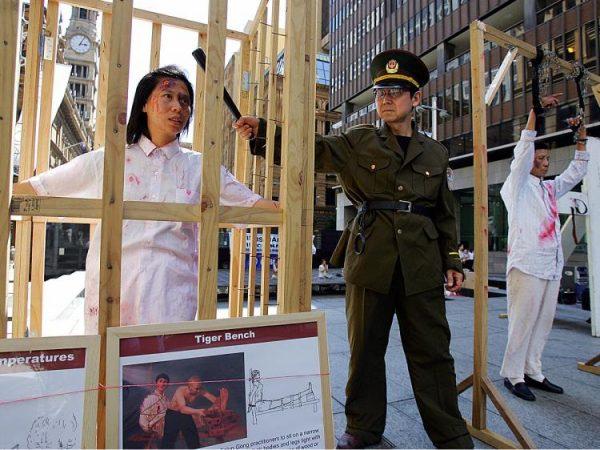

In July 1999, the peace May had found in life was demolished as the CCP started to arrest millions of Falun Gong practitioners. Many were detained without trial in secretive black jails, prisons, and laogai (re-education through labour camps).“Everyone knows that when Falun Gong [practitioners] enter a prison, they get treated the worst,” May says solemnly.

Prison authorities would reward the other inmates for monitoring, torturing, and brainwashing Falun Gong practitioners.

“In the first year and a half I was only allowed to sleep about three hours a day. They would not allow me to sleep until 2 a.m. and wake me up at 5 a.m,” says May.

Every three or five days, a prison officer would check the “progress” of May’s re-education, trying “to intimidate and reason with you [at the same time],” she explains.

The first officer was like the bad cop, he would test her resolve—yelling and threatening her. The second officer was like the good cop, he would come a few hours later and try to reason with May, saying things like: “Look, your children and your family are waiting and want to reunite with you,” she says.

“Imagine being tortured like this every day. That is why you often hear of practitioners going to mental asylums. It drives you insane,” she says. “I would honestly feel better if they tried to kill or shoot me.”

However, the prison officers were tasked with “reforming” Falun Gong adherents and forcing them to renounce the practice. Killing a practitioner was not the goal.

“They will try to break you with what you care about, and insult what you hold sacred,” she says. May knew Falun Gong was good, and tells me the mental duress she was under was absolute “torture.”

Over her eight-year loss of freedom, she was moved to various facilities, enduring horrendous conditions.

In the Fengtai District’s facility in Beijing, May shared a jail cell with 60 other inmates.

The cell contained two large wooden “beds” on which the inmates would rest at night, packed tightly like sardines. The quilt on the bed was “filthy.” Some inmates were ill and had skin conditions. If you got up to use the bathroom, she says, your “spot” on the bed would immediately be taken by another inmate.

A Chance to Live a Life of Purpose

After eight years in jail, May was released, and she made plans to leave China.“In 2012, I escaped to Australia, but I knew I wasn’t here for an early retirement. I had to use my freedom to help those still imprisoned,” she tells me.

She joined a public Falun Gong parade in Sydney for the first time, May says she was overjoyed with happiness. Tears streamed down her face as she soaked up the freedom of Australia.

Started in 2004, the Tuidang movement aims to tell people about the actions of the CCP and assist Chinese people with renouncing their ties to the regime.

To date, Tuidang has registered 350 million withdrawals from the CCP and its affiliated organisations.

May visits popular tourist hotspots like the Sydney Opera House and Mrs Marquarie’s Chair, telling those who listen about the horrors of life in China under the Communist Party.

These sites often receive hundreds of Chinese tourists every day, and Tuidang volunteers speak to them one by one.

“It’s not an easy process to get people to quit, decades of brainwashing have distorted our perception of the truth,” May says. “Many will refuse to believe it. That is the tragedy we are dealing with.”

Despite the challenges, May says she will not give up: “Of course, we don’t match the People’s Liberation Army, nor do we have guns or tanks, but we have our hearts and mouths.”

“We believe that’s powerful enough to free the Chinese people from the biggest dictatorship in the world.”