My friend struggled into his wetsuit. It was a warm, sunny Mediterranean day. I was driving a small motorboat across the bay from the biology research station to Calvi.

“I cannot believe people do this for pleasure,” Daniel grumbled. Sweat was running down his forehead. His beard was wet, and he wore a grumpy but very funny expression on his face. He had put on weight, and his wetsuit was difficult to get on.

Daniel Bay and I had been doing research on the effects of pollution in the Bay of Calvi. Calvi is a walled citadel city in the north of the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea, about 100 miles southeast of Nice.

Corsica is French, but its history and people trace their ancestry to many civilizations. French, Italian, and a Corsican dialect are spoken on the island. Tourism, agriculture, and fishing are the main occupations of the people. The Corsicans welcomed me with warmth, friendship, and hospitality.

Dan, who is from Belgium, was director of the biology station on Corsica operated by the University of Liege for many years. Scientists who specialize in marine biology and oceanography stay at the research station to study and conduct experiments.

“I want to show you something. An American will appreciate this,” Dan told me one morning after breakfast.

We got our scuba diving gear together and loaded the boat at the dock. I slipped into my wetsuit as Dan navigated the boat, then I took the helm and he got ready. He continued to grumble in his funny way that made everybody who knew his good nature laugh.

It only took Dan a moment to position the boat using onshore landmarks. I dropped the anchor overboard. The motorboat was almost in the shadow of a tall cliff that formed a precipice upon which the city’s walls were built, on a peninsula of land commanding a view of the bay.

The colors of the mountains around Calvi, red terracotta roofs of houses on the shore, and the massive walls of the fortified city lent an aura of mystery to our dive.

Over we went with a splash as we rolled backward off the boat, both at the same time to keep the motorboat stable. I took my underwater camera.

I could see it almost at once as I swam down through clear water. It was awesome. The wings of a B-17 Flying Fortress spread out below. The sunken bomber was upright on the bottom, its nose facing the citadel of Calvi.

On this first dive, I swam around the outside of the big airplane. I took pictures of its motors. Some of the propeller blades were bent from impact when the airplane hit the water. One of the four huge motors had broken away from the wing and hung down into the sand.

I swam to the cockpit and shined my dive light inside. The windshield was shattered. The nose cone and tail section were gone; otherwise, the plane was fairly intact.

Just as I was wondering how I could get into the cockpit, Dan directed me toward a gun turret in the roof. The machine gun was gone, but a hole was left where the swivel mount had been.

I wanted to take photographs of a diver in the cockpit. I signaled Dan to slip inside through the hole. He tried. He was too fat and got stuck.

He had an odd expression on his face when he pushed himself out of the machine gun turret. I gave Dan my camera and slipped down through the hole.

A parachute floated behind the pilots’ seat. The nylon was torn in places from the action of the sea after 50 years, but the fabric seemed like it could be used again.

I moved into the cockpit and studied the instrument board and controls. The pilots’ seats remained as they were when the bomber went down. I looked at Dan, who was outside the cockpit. He took my photo through the plane’s shattered windshield.

Many thoughts crossed my mind as I swam back through the intact fuselage of the plane. Wires hung precariously from its aluminum frame. I had to push them aside to avoid becoming tangled inside the wreckage.

Once air bubbles from my regulator struck the roof, accumulated silt fell down and limited my visibility. I was careful not to stir up silt on the floor of the fuselage. The passageway was very narrow and fraught with supports and cables that had broken away and were hanging loose.

My dive light revealed many beautiful colors inside the fuselage. Red, orange, and yellow sponges were growing on the structure.

I swam out a hole at the rear of the B-17, where the tail section was missing. Dan was waiting for me with my camera.

He smiled. I could see the expression in his eyes. I was happy to have shared this adventure and signaled the OK that divers use before we swam up to the surface.

“Eh, l’American,” Dan said when we got back aboard the boat. I nodded my head. It was awesome. Dan was pleased to have been the first person to show me the sunken U.S. B-17 bomber.

We didn’t talk much on the trip back to the biology station. We were both deep in thought about the history and events of World War II that brought this bomber to its underwater grave off Calvi.

During my stay at the research station, I returned to the sunken plane as often as I could. I photographed it and filmed it. I searched the area behind the bomber in deeper water looking for the tail section. I found landing gear that was sheared off when the plane struck the water.

Little by little, I learned some of the history of the B-17. People on the island remembered the war. Some saw the plane go down.

One day while I was filming inside the fuselage, I stirred up some silt with my fins. I had to wait until it settled to resume filming. I swam outside and began looking over the controls. I moved ailerons on the wing.

Since they were made of aluminum, they were not corroded by saltwater. I could work them up and down with my hand. The control cables remained intact.

When I thought the silt had settled, I swam back inside carefully. In the spot where I had stirred up the silt, I saw what appeared to be a piece of wood.

I fanned the spot gently with the side of my hand. I could see writing on the wood and knew it was part of the B-17’s equipment. I fanned some more and exposed a small ampule of iodine. I recognized it at once. I had discovered the bomber’s first aid kit.

I continued to fan the little area. I saw something else in the silt. I knew immediately what it was. I fanned again. The small object popped up, then fell down out of sight in the clouds of silt. I fanned once more with the side of my hand to clear away the silt, and I picked up the object.

It was an aviator’s dog tag. I could read the identification stamped into the metal. I put the ampule of iodine and dog tag into a pocket of my diving vest, got my camera, and swam to the surface.

Aboard the motorboat, I showed my finds to P’tit Lu, a friend who worked at the biology station and often dove with me.

He studied the objects then handed them back to me. We didn’t speak. We knew the consequences of finding the first aid kit and aviator’s dog tag: It was evidence that someone had been injured or killed inside the bomber.

Looking for Survivors

I wanted to know if there had been survivors of the crash landing and whether any of those World War II aviators were still alive.My quest hit many dead ends. I was able to find information about the plane itself. Boeing Aircraft Co., the developer of the Flying Fortress, was very helpful. They took an interest in my work and sent me photographs of B-17s in production and action during World War II.

I also searched telephone books at the library, and wrote to R.H. Householder at the address listed on the dog tag; my letters were returned unopened. I wrote the police chief in the town, the post office, the military, too.

The B-17’s crew was part of the U.S. Army Air Forces; the U.S. Air Force didn’t come into existence until after World War II. Many military records were destroyed in a massive fire at a storage facility.

The Department of Veterans Affairs would only say that nobody by the name of R.H. Householder, the name on the dog tag, ever applied for benefits. I persisted and wrote many letters.

Dan and I had discussed one day holding a memorial service on the island of Corsica to commemorate the war dead. Our hope was to locate survivors of the crashed B-17 and bring them to Calvi for the ceremony.

It was the year of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II. Corsica had been a rallying point in the war. Fiercely independent, islanders became secret resistance fighters against German occupation.

The very word Maquis or Maquisards, used in the war to describe resistance fighters, comes from the name of tangled bushes in the Corsican Mountains where they hid during the war.

I was asked to preside at an international film festival to be held in Corsica. With visitors from all over the world converging on the island, I thought it would be a wonderful time to hold the memorial ceremony. I worked harder to locate surviving crew members of the B-17.

But other than the name on the dog tag, I had no one else.

About two weeks before I was to leave for Corsica, I received a phone call from a U.S. Air Force major in the Pentagon. I remember his exact words: “I’m shredding documents in the secretary of the Air Force’s office. I was about to shred your letter to the secretary when I read it. I studied history and was fascinated by what you wrote. Has anyone helped you on this?”

I answered no. This call was my only hope. I explained that I was planning to travel to Corsica to preside over the film festival and wanted to conduct a fitting tribute to honor those who served in World War II.

He promised to try to help. We hung up. I was excited at the possibility of finding survivors of the sunken bomber. I had almost given up.

Within an hour, the Air Force officer from the Pentagon called me again.

“I have a list of crew members for you. I’ve found three survivors,” he said. My heart soared. I took the names and began trying to contact the surviving crewmembers of Calvi’s sunken B-17.

Of the three names, I located two. I spoke to the pilot, former 2nd Lt. Frank Chaplick, and to the bombardier, former 2nd Lt. Armand C. Sedgeley. The crewman whose dog tag I found, Tech Sgt. Robert H. Householder, was killed in action along with two others. Seven survived the crash landing.

I called the pilot. Chaplick was living in Maine. I told him what I had discovered and that I planned to organize a memorial service in Calvi. He was willing to attend. I also called Sedgeley, who was living just outside Denver; he was enthusiastic and also wanted to attend. His concern was his need to travel with a companion.

An Idea

The willingness of these crewmen to participate was all I needed. I called Corsica and spoke to my friends. Dan, who was surprised by the news, promised accommodations at the biology station for the survivors. I spoke to the organizer of the film festival in Ajaccio, the capital of Corsica. He was enthusiastic about the idea, but thought the time was too short to organize anything.I spoke to people at Boeing, who said they wholeheartedly supported the project. My idea was to have a bronze plaque made that could be placed underwater at the site of the sunken bomber, marking it as a war grave and memorial to World War II.

I reached out again to the officer in the secretary of the Air Force’s office. He was very helpful and got the project on the secretary’s desk, along with articles I had written about the sunken bomber.

The Air Force Museum told me about a plaque maker who made their bronze castings. However, they thought the endeavor was impossible since it required months to make a plaque of the size I wanted. A call to the foundry revealed that was owned by a former German citizen who came to America and made his home in Ohio after the war.

When I explained why I needed the plaque urgently, I was promised that it would be ready in time. I had to supply the names of the crewmen who survived and use stars for those who had been killed inside the B-17. I sent them an outline of the Flying Fortress and the numbers of the aircraft, which they would use to make a relief of the memorial plaque.

French and U.S. military authorities were cooperating. I left the organization of Corsican authorities to Jacques-Donat Casanova, the film festival’s director, who wasn’t convinced that I would get the project organized.

It was funny. Military authorities have their own way of organizing things. Ranks for protocol must be equivalent. French authorities asked me what rank the Americans were sending, so they could send an officer of equivalent rank but not higher. I kept raising the ranks higher and told the Americans that the French were sending a general.

Then, the pilot, Chaplick, called at the last minute, saying that he couldn’t travel. His brother was critically ill and he had to stay with him. In addition, the bombardier, Sedgeley, was retired and didn’t have funds to pay for the airfare to Corsica.

There were no funds available; I had never thought about that part of the plan. Of course, I would have to find help for the survivor and his companion to travel to Corsica.

I had contacts at the Denver Post, so I called the editor and explained what I was doing. I told him that a survivor, Sedgeley, was living in his city. He wanted the story. This was the 50th anniversary of World War II and it had all the hallmarks of a good article. I faxed the editor copies of my articles about the sunken B-17 bomber.

The story about the ceremony ran as front-page news in the paper. The Denver Post interviewed Sedgeley, who told them he wanted to attend the ceremony. He received a telephone call from the chief pilot of United Airlines, which has its pilot training facility in Denver.

“Do you want to go?” United’s chief pilot asked.

“I don’t have the money,” Sedgeley replied.

“I didn’t ask you that. Do you want to go?”

When Sedgeley replied that he did but required a companion to fly with him, United’s chief pilot said he would get two free tickets from Denver to Milan, then to Corsica.

I was relieved at this news. My own flight was scheduled to depart and I hadn’t received the plaque. When I called the plaque maker, I was told it was in transit with Federal Express. I told them I was leaving that night for France, then traveling to Corsica.

I got in my car and drove around to look for the FexEx truck. I knew they usually delivered early packages to neighborhood stores at a shopping center in my town. There he was, driving away from his first delivery. I swung the car around and drove after the truck. I beeped my horn and the driver stopped.

The FedEx driver smiled when he saw me.

“It’s a heavy one,” he said when I signed for the large package. It was heavy, and left me wondering how I was going to pack it to take it to Corsica.

I already had packed my underwater photography gear and had only a two-suitcase allowance. I unpacked one suitcase and put the large plaque in it. It barely fit and was so heavy I could only toss some clothing in to protect it.

I called the White House. President Bill Clinton had been made aware of the project and, while he couldn’t attend, the president sent a special message for me to bring to Corsica. It arrived the morning of my departure.

That night, I flew to Paris. By morning when we landed, I planned the phone calls I would make from the airport. I called my dear friend Philippe Tailliez and his wife Josie in Toulon.

Tailliez was the French Navy commander who brought Jacques-Yves Cousteau into diving and was Cousteau’s commanding officer on ship and also when Tailliez organized the French Navy’s Underwater Research Group.

Josie was glad to hear my sleepy voice from the airport. We talked not about the ceremony but only personal news. When she put Tailliez on the line, he was thrilled. He spent his entire career in the French Navy and, like his father before him, attended the naval academy and rose to command after his service in World War II.

Tailliez, who was 87 years old, would come to Corsica and dive with me to put the memorial plaque underwater on the B-17 bomber.

I then called my friends in Corsica to tell them I had landed and would arrive on the afternoon plane to Ajaccio.

“What did you do?” Dan said from the other end of the phone. “You told me four people were going to stay with us. I have 25 so far. Who will feed them? I have to get more beds set up.”

Normally, Dan was unflappable and cool. His voice was excited.

“The mayor wants to talk to you. He has been calling every hour,” Dan said, and we hung up.

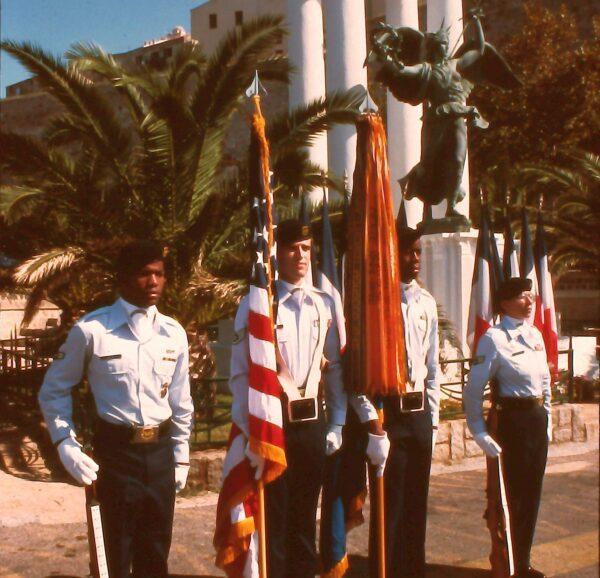

I wasn’t sure what happened. I only knew that the U.S. Air Force promised to send a color guard from the airbase in Ramstein, Germany.

I arrived at the Ajaccio airport late that afternoon. Casanova met me at the airport and we drove to his house. It overlooked the Gulf of Ajaccio from a mountainside.

Casanova was more excited than Dan. He was very enthusiastic but told me that because he didn’t believe that I could pull the project off, he had informed the authorities but didn’t organize anything. He said Corsican government offices were getting calls from high-ranking French and U.S. officials, asking questions they couldn’t answer.

“Is the survivor coming?” Casanova asked. I replied that the last I heard, United was giving him a ticket.

Starting an Avalanche

The French commanding general of land forces on Corsica, and French Navy officials with the mayor and city council of Ajaccio hosted a celebration in the city, with drum and fife musicians marching in Napoleonic-era military dress.I unveiled the bronze plaque, which was the centerpiece of the celebrations. There were toasts and speeches. The unveiling of the plaque was very moving.

Tailliez was there, as were many of my Corsican friends from diving. Dan arrived, but could only shake my hand quickly since the ceremony was about to begin and I was whisked away. Throughout the event, he gave me the most tormented look from across the room.

“There are even more coming,” he managed to say. “What am I going to do with them? You have to come to Calvi and straighten this out.”

We closed the film festival the next day. Tailliez and I flew in a small plane to Calvi. We were picked up by Dan and traveled to the biology station to unpack. Meanwhile, the telephone never stopped ringing.

“It is the mayor. You have to go,” Dan insisted. I was in my shorts and T-shirt hoping to be able to dive in the little bay in front of the research station.

“Take the boat. Hurry up. The mayor wants to see you immediately,” Dan ordered, making believe that he was grouchy. This time, however, I think he was. I got in the motorboat and went across the bay to the city. There were large cruise ships and fishing boats tied up as I navigated into port and pulled up at the quay.

When I got to city hall, the office was a beehive of activity. I introduced myself to the receptionist. “Oh it’s you,” she said and called the mayor’s secretary. I didn’t realize that all of this activity was because of the ceremony.

The mayor came out of his office and down the hall to greet me. We had just sat down in his office when his phone rang.

“The governor wants to see you. You must go. I wasn’t told about this. I had no preparation. All of these officials are arriving. How am I going to handle this?” The mayor seemed quite nervous. He was very willing to get me going to the governor’s office.

“The governor is sending his car and driver,” the mayor said. The car was waiting for me when I got outside. I was whisked to the governor’s stately offices.

When the governor saw me in my sandals, T-shirt, and shorts, he laughed.

“It’s you, Fine, who has started this avalanche?’

I smiled. Until then, I didn’t know exactly what kind of avalanche I started but I could see I was about to find out. The governor ordered coffee and cake and we sat in his spacious formal office and drank the coffee.

While we were drinking coffee, unhurried to get down to business, the governor’s phone rang. He spoke to his secretary in French. He ordered his chauffer to the airport and designated other drivers to take vehicles.

“The U.S. Air Force jet is arriving now,” the governor said calmly. I just nodded and dipped a delicious Corsican cake into my coffee.

“I have been called by the director of France’s Veterans Affairs. They are organizing veteran’s organizations,” the governor said. He resumed his seat at a little table across from me.

The governor of Corsica had been a French military pilot, who trained at Ramstein Air Base. He had the cool of a combat aviator and a youthful sense of humor.

“The mayor seems a very nervous sort,” I told him. The governor laughed.

“You have made everybody on Corsica and many on mainland France very nervous. They don’t know what to do about all this,” the governor said. His eyes twinkled with laughter. He was quite enjoying the whole project. I could tell immediately that he was wholeheartedly for it.

His phone rang again. It was the mayor.

“Yes. I will organize it. He is with me now. The American Air Force jet arrived. I know. I sent my cars to pick them up. Yes. Their public relations colonel will be driven to my office. Don’t worry, I’ll handle it. Now what about the costs? I see. Your office will pay. The reception? Yes. It will be billed to your office? Yes. I’ll handle it,” the governor said into the telephone.

When the governor got off the phone and hung up he had a big smile on his face.

“The mayor is paying,” he said.

The governor’s secretary rang the intercom. The U.S. Air Force colonel was outside. He had the officer shown in. They saluted and we shook hands.

The public relations officer seemed a little nervous himself. It was his job to see that everything worked smoothly. It wouldn’t do for the U.S. contingent to be received in a less than appropriate fashion.

The governor spoke to the officer. We both assured him that we were handling all of the details and that everything was set for the ceremony to be held the next afternoon. The U.S. colonel was not so sure, but the governor and I were quite confident. The governor’s secretary brought him coffee. The colonel didn’t speak French.

We had work to do, the governor and I, and it wouldn’t do for the colonel to see that all the preparations had not been made. In fact, as we sat there in the governor’s office, nothing had been done.

I told the governor in French that it would be better to send the colonel to the biology station where he could join the officers and personnel of the U.S. color guard and relax, since we had some details to work out.

The colonel was still unsure that he should leave, but we convinced him to go rest after his flight. We said that we would join him that night for a late dinner at the biology station. The colonel left to be driven by the governor’s chauffer to the biology station.

“How are you going to get the spectators to the site of the bomber in the bay without a ship?” The governor asked me. “The television media and newspapers are sending reporters.”

I hadn’t thought of that. I assumed we would have a ceremony onshore, then Commandant Tailliez and I would go out in a small boat and lay the plaque underwater.

With international news media coming to cover the event and dignitaries arriving, it was important to have a ship to accommodate them.

I asked about the Gendarmerie; the French National Police had boats.

“Too small,” the governor said.

“Colombo Line,” I said. It just came to me. The Colombo Line offered tours around Calvi and Corsica. They had large ships designed for great numbers of tourists.

“Who will pay for it?” The governor asked.

“They should do it for free,” I replied innocently. The governor laughed.

“You call them and introduce me. I’ll ask,” I said.

The governor was very doubtful that Colombo Line would donate the use of one of their large ships and crew, but he had his secretary call them and get the director on the phone. The governor spoke briefly to the director, then handed me the phone.

The director was friendly. He heard what we were doing from newspaper and radio reports. He said he would be proud to participate and that we could have the boat the next afternoon.

The governor rubbed his chin. He was surprised that we were able to get the boat, although I wasn’t surprised at all. This was to be a patriotic event and we were in Corsica, the place where resistance to Nazi occupation of Europe began, where forces rallied against the oppression of fascism.

The governor used his intercom to call in his assistants. Issuing rapid-fire orders, he got the wheels in motion for a formal reception in the gardens of the governor’s palace the next afternoon before luncheon.

“Who is going to pay for the luncheon?” the governor asked me.

“Why do we have to feed them?” I asked.

“We must feed them. They have to eat. That’s how these things are done,” he said in French. “We will have the ceremony in the morning then the reception here in my gardens, then luncheon, then they will board Colombo Line and you will dive with the plaque.”

It was simple enough, but there was still the question of who would pay for the formal luncheon for the guests, veterans, military officers, and the survivor and his companion.

“When is the survivor arriving?” The governor asked me. I answered that he should be flying in that afternoon. I didn’t know exactly, since the last I had spoken to him was before I left the United States.

A Wonderful Evening

I arrived at the biology station late, docked the boat, and joined the gathered guests on the large patio outside the kitchen, facing the little bay.It was a late sunset on the other side of the peninsula. I saw it from the water. As I greeted everybody assembled with drinks and snacks, wisps of clouds and the outline of Calvi across the water radiated velvet shades of pink.

Sedgeley and his son arrived, and the B-17 bombardier was the center of attention on the patio. We shook hands warmly.

My friend Tailliez embraced me. Dan, his wife, and the cook were very busy in the kitchen with students from the biology station trying to get dinner prepared for so many people.

After greeting everyone, I went into the kitchen and told Dan that the governor and his adjutants were coming for dinner. I hoped it was alright that I invited them.

“If you invited them, it has to be alright,” Dan grumbled. “How am I going to accommodate all these people? I have no more rooms if the governor is going to stay the night.”

“No,” I said, “The governor won’t stay over.” Dan didn’t answer, he only grumbled. I thought it best that I get out of the kitchen.

Dan had converted the lighthouse on a hill above the biology station into accommodations; Tailliez and I would sleep there. The U.S. military officers and color guard, the survivor and his son, and the other guests would stay in dormitory rooms at the biology station.

When I returned to the patio, Tailliez was talking with the B-17’s bombardier. He arrived with his son without a hitch. United Airlines had provided the free tickets and he had been treated royally on his flights.

It was a wonderful evening. The governor was late arriving. Dan had begun serving dinner by the time he arrived with his adjutants. The unpaved road along the narrow peninsula from Calvi to the biology station was strewn with rocks. It took them a long time to get there in their touring car.

“You must stop by the Gendarmerie,” the governor told me. We sat at tables on the veranda in the warm Corsican night.

“The chief of the French National Police here wants to meet all of you and welcome you. He will have a little event at headquarters tomorrow,” the governor said.

Casanova, the organizer of the film festival, was there. He agreed to pay for the luncheon out of his budget. Everything seemed ready for the ceremony, which was to be held the next day at 11 o’clock in Calvi’s main plaza, in front of the war memorial.

Tailliez reminisced about his days commanding the French Navy’s Undersea Research Group with his legendary friends Cousteau and Frederic Dumas. By the time dessert and coffee were finished, all the guests were ready for bed, since most had traveled long distances to Calvi.

The governor and his adjutants bid us goodnight, and reminded me again of the schedule. The governor reminded me again to be sure to stop by the Gendarmerie headquarters before coming to the plaza for the ceremony.

The Day of the Ceremony

We awoke early and had breakfast on the patio terrace as sunrise came up over the citadel of Calvi. After breakfast, I got the diving equipment ready in the motorboat with Dan. I couldn’t return to the biology station to change my clothes, so I had to gather my gear aboard the dive boat. I would wear a suit and tie for the ceremonies.We went in a small group to the headquarters of the French Gendarmerie. We were greeted warmly by the commanders of the post in their dress uniforms. Beverages and snacks were set up for us. Sedgeley was welcomed with open arms as the war hero that he was.

For the Corsicans, the bombardier who had survived the crash of the B-17 symbolized heroism that liberated their homeland from German occupation.

A .50 caliber machine gun was bolted to the wall inside the Gendarmerie headquarters. The French commander told us how the police seized the machine gun from German divers who had removed it from the B-17 and were getting ready to loot it.

I asked if the machine gun could be unbolted and brought to the formal ceremony at Place de Mort—the memorial plaza, where the war dead were honored and where we would hold the open-air ceremony.

“Mais bien sur,” of course, the French Gendarmerie commander said and gave orders for his men to remove the machine gun. Tailliez and the survivor were enjoying the good company at Gendarmerie headquarters, but Dan prudently suggested we had many things yet to do.

We would meet them all later at the plaza for the ceremony. We returned to the biology station, finished loading the dive boat, and got aboard. Everybody else would go by vehicle. Tailliez and I would take the dive boat. It was as it should be.

Tailliez and I had shared many wonderful dives together. We worked on books and articles and enjoyed discovery of the undersea. Tailliez was a diving pioneer. Now, we would share my discovery together in a special way with an underwater ceremony that was to follow the formal ceremonies on land.

I tied up the boat and we walked to the Place de Mort. The streets were crowded. It was the busiest time of day in Calvi. A warm sun greeted us as we approached the wide plaza.

A large crowd of people that had gathered for the ceremony lined the plaza. The police had closed the area off to traffic, and a podium was set up in front of the memorial arch that honored war dead.

The U.S. Air Force color guard was assembling, as were contingents of French war veterans and uniformed services from every branch of France’s military and civil services.

The crowd made way for us to pass. We walked over to where the mayor and governor were talking with the bombardier. It was a heartfelt greeting as Tailliez embraced a fellow World War II veteran.

I went to the podium to meet the Archdeacon of Corsica. He had prepared an invocation, and I was to give the translation in English. It was a very moving prayer. I read it in French then nodded to the priest that I would do the translation when he finished in French.

Then, I was completely alone, behind the podium at the Place de Mort. The memorial was white marble, with bronze plaques that commemorated the dead from many wars. The B-17’s machine gun was placed against the memorial as I had asked.

I brought an American flag with me to Corsica, which I draped over the bronze plaque that had been placed on the memorial, so that it would be visible to all.

I said a silent prayer for those who lost their lives aboard the sunken bomber. When I stepped away, I was surprised to see the plaza completely filled with people, including contingents of dignitaries from France and the United States.

French war veterans lined up closest to the memorial arch. There was still time as final preparations were made, so I went down the long double lines and shook hands with them. Some shook with their left hands; some had lost legs; many were gravely wounded in the war. They wore their military decorations proudly; great pride showed in their eyes.

The mayor and governor approached and told me that it was time to begin. I was to make the introductions from the podium. As I spoke in French into the microphone, the crowd in the plaza fell silent. Shops closed and cafes were quiet.

The Archdeacon of Corsica intoned his prayer. I translated it without reading from his paper and saw the priest’s eyes glistening. He understood English and was hearing his prayer for the veterans on this occasion spoken by another.

Many speeches followed, including from the mayor and the governor, resplendent in his formal uniform, its gold braid reflecting rays of sun. They spoke with emotion.

When the B-17 survivor approached the podium, a new hush fell over the crowd. It wasn’t what he said, it was that he was there. For all those assembled, Sedgeley, who was a 24-year-old second lieutenant when the plane went downed, symbolized the battle for freedom.

The colors were presented and the music stirred us. With the formal ceremony over, we marched in procession to the governor’s offices. I walked with Tailliez, while friends from the biology station took the bronze plaque down to our dive boat.

When I saw the garden in the governor’s offices, I smiled. I recalled the admonition to his aides when he ordered preparations.

“No chips. No peanuts. Order the very best. Champagne,” he said, then added, “The mayor is paying.”

It was the very best. Waiters in starched white linen coats and black bow ties served delicious Corsican entrees. Champagne was passed around on trays in crystal fluted glasses. I translated for Sedgeley, who was surrounded by well-wishers.

Corsicans came up to him on the street on the walk to the governor’s office and pressed flowers into his hands. Women kissed him on the cheeks. “Ancien combattants,” French war veterans, came up to him tearfully; they held me by the arm so I would translate.

“I was stationed with a rifle in the lighthouse that day. I saw you fly over and crash into the sea,” one man said emotionally.

A woman approached. She was shy and waited patiently for her turn. She handed the bombardier a rose and kissed him on both cheeks.

“This is for my father who died in the war,” the woman said. Tears welled up in her eyes and streamed down her cheeks. The woman quickly disappeared into the crowd again even before the bombardier could reply.

The appetizers were truly delicious, made in the tradition of finest Corsican cuisine. I reached for a fluted glass of champagne and proposed a formal toast. Everyone paused their conversations and raised their glasses.

Before I could take a sip of the champagne, a friend from the biology station took the glass out of my hand.

“You have to dive later,” Pierre Lejeune reminded.

Until then, I didn’t realize that all my friends from the biology research station were there. They were all lending a hand, helping with the guests to be sure they got to the governor’s offices and that things ran smoothly.

“But it is the best champagne,” I protested with a laugh.

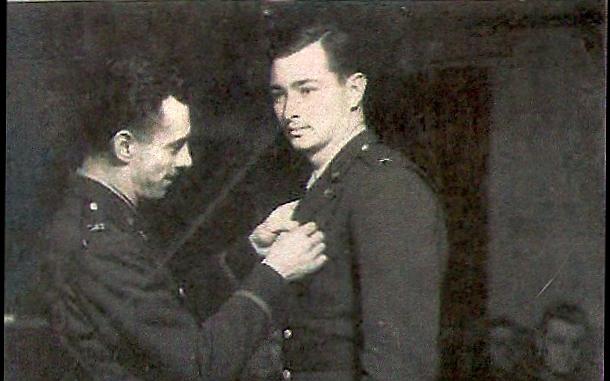

The governor then called for silence. Here in the resplendent garden, the festivities stopped. French officials presented medals and decorations to this ancien combattant who survived the crash of his B-17 Flying Fortress.

The commandant of Corsica’s veterans organization, displaying a great cross of the Legion of Honor and medals on his chest, presented a book he wrote about the liberation of Corsica.

There were many medals and many honors bestowed upon the bombardier for what he had done when he was a very young man in wartime. Many, too many for him to carry, so his son took them in a large sack.

I introduced Tailliez, and described his naval service and the dive we were to undertake with the plaque after the luncheon.

Slowly, the gathering at the governor’s offices dissolved and attendees made their way down to the port where tables had been set for the luncheon.

Long tables with white linen tablecloths were set under awnings outside a restaurant in the port. I arrived a little late, walking slowly with Tailliez. We took seats. I sat next to the commander of the veterans, Tailliez across from me.

The governor made more toasts to the veterans and to French–American friendship and for their sacrifice to preserve freedom and liberate France.

My luncheon companion ate with one hand and had a patch over one eye. One of his legs was gone. He fought in the war, was captured by the Germans, and had been sent to a prisoner of war camp.

The veteran escaped from the German prison and was able to make his way to Switzerland. From Switzerland, he rejoined Free French forces. He received his terrible wounds in combat helping to liberate his country.

The Dive

The luncheon was served in several courses, and took a long time. A friend from the biology station came up behind my chair and whispered that I had better get ready for the dive.I wouldn’t have time to savor my favorite part of the meal, so I excused myself before dessert. I told Tailliez that I would return for him when the dive boat was ready.

I stepped aboard the dive boat that had been tied up to the nearby quay. I had to take off my suit and tie, put on my bathing suit and get into my wetsuit in preparation for the dives. I put a towel around myself until I got my bathing suit on, then slipped into my wetsuit.

We were behind schedule, and my friends were concerned about the time. I was now in my bare feet, wearing the wetsuit. I was told that the Colombo Line ship was waiting and that we had better start getting the dignitaries and veterans on board since the press was already set up.

I walked along the stone quay to the restaurant in my wetsuit and bare feet. The governor was sitting at the head of the table nearest to the water. I bent down and whispered into his ear that we should get the people started to the Colombo Line ship. He nodded, but it seemed that everyone was still savoring the wonderful luncheon and good fellowship.

I returned to the boat and shrugged to my friends, who were very practical in their observations. The press and the ship were waiting. After a while, they persuaded me to return once again to the restaurant and start the dignitaries, the color guard, the veterans, the survivor, and guests toward the ship.

The luncheon was still buzzing with conversation. It was a warm atmosphere of friendship among the Americans and French. I saw it would be useless to interrupt the governor again. He was deep in conversation with the officer from the U.S. Air Force. They shared a pilot’s kinship.

I went inside the restaurant, past waiters in starched white jackets and French “tabliers” or formal white aprons, to the hat rack.

“Where is the governor’s hat?” I asked the maitre. He looked at me in my bare feet and wetsuit and smiled.

“I need his hat,” I said in French and smiled. The maitre wasn’t so sure, but he pointed to the hat rack. I took the kepis, a peaked hat that French officers wear, with its thick gold braided leaflike clusters, pulled up my wetsuit hood, and popped it on my head.

I went outside the restaurant, walked behind the governor, and blew my dive whistle. Conversation stopped, silence, then laughter as I invited the attendees to begin walking to the Colombo Line ship down the pier. It did the trick. Slowly but surely the celebrants left the table and walked down the dock to their ship.

Tailliez, the governor, and I paused to talk and take pictures together. The governor, a youthful and good-natured man, laughed then took back his hat for the ceremony that was to follow aboard the Colombo Liner.

Tailliez and I headed for the small motorboat. It was a magnificent day and the sea was calm. Pierre Lejeune, my friend from the biology station would pilot the boat around to the dive site.

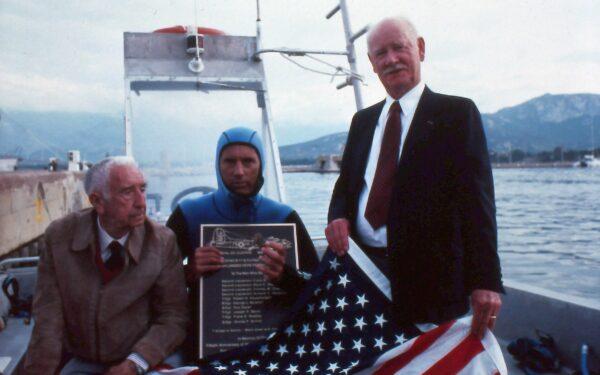

We arrived long before the Colombo Liner and anchored over the sunken wreckage of the B-17. In the calm, Tailliez and I sat quietly. I got into my dive tank as Lejeune readied the bronze plaque. I placed the folded American flag into my wetsuit.

The large ship came up and the captain skillfully turned his stern toward the citadel of Calvi. The poop was very high; the liner dwarfed our little dive boat. Tailliez and I stood in the motorboat and waited. We looked up at the people aboard the Colombo Line ship.

The Archdeacon was saying a prayer. A wreath was thrown overboard as news media filmed the events. Tailliez put his arm around my shoulder as the prayer was spoken and the formal memorial ceremony aboard the liner conducted. We could barely hear what was said.

“He wants you,” Lejeune said in my ear as the celebrants now ringed around the stern of the big ship. I looked up. The Archdeacon was motioning to me with his hand. Lejeune skillfully backed our boat under the stern and the priest handed me down a little vial containing holy water. He did not have to tell me what it was or what to do. I put it carefully inside my wetsuit with the American flag.

Lejeune repositioned the dive boat on its anchor line and asked me if I was ready. I was and slipped overside. I inflated my dive vest with air to receive the heavy bronze plaque.

Lejeune passed it down to me.

“Are you ready,” he asked. I grunted through my regulator and took the plaque in my hands. It was so heavy that even with the air in my dive vest I sank like a stone to the bottom.

I couldn’t swim with the heavy bronze plaque, so I struggled to walk it along the bottom toward the sunken B-17. With great effort, I swam the plaque up to the cockpit and placed it there. I then unzipped my wetsuit and removed the vial of holy water and the American flag.

I unfurled the flag so that it fluttered in the sea around the memorial plaque, then released the holy water in a church ritual for the souls who had perished in the sunken aircraft 50 years before.

I was in no hurry to return to the surface. My part of the ceremony was done. I swam underwater eventually joined by divers from the biology station who took photographs. I heard the engines of the Colombo Liner churning; the sound was loud underwater then it faded away as the ship left to return to port.

For me, this was the most important moment of the ceremony. It was where honor was returned to the sea. Those who made the ultimate sacrifice in wartime were themselves finally liberated by prayers of remembrance bestowed by two grateful nations.

That night, I asked Sedgeley if he wanted me to give him a dive mask and take him to the sunken B-17 so he could lie on the surface and look down at his plane.

“No. I will leave it as I remember it,” he said. There were tears in his eyes.

The underwater ceremony at the site of the sunken B-17 bomber was the last official ceremony commemorating the 50th anniversary of World War II—a war fought with great sacrifice to preserve freedom.

Facts About B-17

The B-17 heavy bomber was a formidable fighting machine. It was designed by Boeing Aircraft Co. of Seattle. The plane was called a Flying Fortress. Later models, called B-17G, were able to carry more armament. The sunken bomber was a B-17G.Equipped with 13 .50 caliber machine guns, the Flying Fortress was well able to defend itself. Machine guns were set in rotating turrets in the chin near the nose, at the top in the back of the pilot’s compartment, and in a ball turret in the tail of the plane. Machine guns were also set along the fuselage in the radio room hatch and in the waist.

The B-17, which wasn’t a fast plane, was powered by four Wright 1,200-horsepower radial engines. While the operational speed was rated at 300 mph, those used in the European theatre of the war rarely exceeded 250 mph. Flying in formation toward attack targets, the squadron was limited by the speed of the slowest plane in the group.

The B-17G, an enormous plane for its time, was 75 feet long, with a wingspan of 104 feet, and weighed 54,000 pounds. The bomber, with its usual crew of nine to 11 men. could operate at a maximum ceiling of 35,600 feet, and had a cruising radius of 700 miles. Its bomb load was 9,600 pounds.

The Flying Fortress cost about $250,000 to build during World War II.

Military designations for aircraft were B for bombardment, P for pursuit airplanes (fighters), C for cargo, A for attack, and O for observation. Numbers usually stood for the order and sequence that the Army Air Forces (AAF) accepted the designs.

During World War II, 12,761 B-17 bombers were made; 4,750 of them were shot down or lost in combat missions.

The Mission and the Men

Sedgeley’s B-17 took off on Feb. 14, 1944, from Amendola Air Base in Italy. The allies had begun the liberation of Europe and held southern Italy. The squadron of B-17s was to bomb railroad installations at Verona in the north of Italy.The pilot was debriefed after the crash landing in Calvi and reported, “As I was on the extreme outside of the turn undertaken by the formation [while the B-17s approached Verona], I was isolated. At that same time, enemy planes came after me, damaging one engine as well as the compressors of two other engines … several attacks later damaged the plane itself.”

The pilot continued his narrative, “The bombardier released the bombs just before the B-17 took a 20 mm shell through the bomb compartment.

Sedgeley, who was the bombardier, described the attack by one German fighter plane.

A Messerschmitt 109 came around the right wing, parallel with us. As the Hun got even with the nose, he made a left turn and started in toward the nose. I started firing … he turned and kept firing until he exploded. After shooting down the Me 109, I noticed two P47s [U.S. fighter planes] approaching from ahead and the Me 109s left us immediately.”

He described what happened next: “We were still at high altitude when the fighters left … the navigator’s oxygen was gone (knocked out by enemy shells) but I still had mine. I gave the navigator my oxygen mask and went to the cockpit and got morphine from the pilot.

“I left the cockpit and went back to the radio room immediately. I found the radio operator lying face down on the floor. I turned the radio operator over and saw a bullet wound in his left eye. He was badly shot up in the legs.”

Sedgeley then checked on the rest of the crew.

“Went to the waist where I saw the left waist gunner lying face up on the floor, and the right waist gunner sitting down in pain. … I had the ball turret gunner help me carry this man to the radio room where it was warmer. I took off his flak suit and unfastened his electric suit. I discovered a bullet wound in his chest, and another larger hole in his belly. I left him as dead,” he reported.

While the stricken B-17 continued its flight, Sedgeley tended to the wounded.

“The next thing came over the interphone was the tail gunner’s voice saying that he was dying. … I knew we were hit from the rear because the nose was full of smoke and dust.”

When Sedgeley got to the tail section, he reported: “I found the gunner lying on the floor, bleeding so much that the floor was covered. I gave him a shot of morphine. His legs had been directly hit by 20 mm [bullets] and they were badly severed. I tried to move him out of the tail but could not, even with help. I tried to stop the flow of blood but could not. He went unconscious and I believe he died.”

The pilot diverted the shot-up B-17 to Corsica, which had already been liberated by resistance fighters and allies.

The pilot, 2nd Lt. Chaplick, described what happened: “As we came in sight of Calvi airport, which was a very short runway and mountains on each side, a lot of smoke was coming out of the engines. I tried to land on the runway without success and opted for a sea landing. The plane did not break during landing and remained afloat for about two minutes.

“The crew managed to leave … but did not have time to remove the bodies of the dead. The survival floats worked and we were rescued by a British Air-Sea Rescue Team.”

My research led to records of the Army Casualty and Memorial Affairs Department. French divers had discovered the sunken B-17 and found human remains inside the sunken aircraft. They contacted American authorities, and June 1965, French divers, under the supervision of a U.S. mortuary representative, recovered the remains from the sunken B-17.

The Army mortuary report read “Unknown X-9386 was determined to be the remains of a person approximately 25 years of age, five feet seven inches tall, who weighed 145 to 165 pounds, and wore a size 8 D shoe.”

The remains belonged to Tech Sgt. Robert H. Householder, the B-17’s radio operator; his service number matched the one on the dog tag I discovered.

While seven crew members survived the crash landing, three men died. The tail section, containing the remains of the gunner, sheared off on impact and while I searched for it in deep water behind the sunken bomber, I never found it.

One survivor felt pain in his belly during dinner the night of the rescue, leading the crew to think he had peritonitis. It turned out that the man had been shot directly through the rectum, and the bullet was lodged in his intestines. Sedgeley said the man was taken to a hospital in Calvi, then was evacuated to a larger hospital in Bastia in the north of Corsica.

The crew never heard anything more about the wounded man. Until I made contact with the survivors, none had kept in contact after the war.

“We were all young men, most just 20 years old. When we returned to the states, we got on with our lives and never got back in contact,” Sedgeley said.

The memorial to young men’s courage in the face of wartime adversity has finally emerged from the sunken wreckage of Calvi’s B-17 bomber.

Postlude

Lt. Sedgeley, the hero of this doomed combat mission, is now 99 years old and lives in home hospice care just outside Denver. His mind, memory, spirit, and voice are perfect; his heart is failing.Despite efforts to see him awarded a Silver Star—the United States’ third-highest military decoration for valor in combat—the lumbering bureaucracy of the Army has refused to act. Like his fellow bombardier in World War II, Joseph Heller, who wrote the prize-winning book “CATCH 22,” Army officials ask impossible questions:

Got witnesses?: Lt. Sedgeley is the last survivor.

Got his personnel files so we can see why he didn’t get the medal at the time?: The Army well knows all personnel files were burned in a fire in their warehouse in 1972.

Catch 22.

Many have been trying, in vain, to get President Joe Biden as commander in chief to issue the medal to this valiant combat hero. Will any desk-bound politicians honor this last survivor before he dies? They’d rather talk a good game about veterans, then play golf.

A nation that does not honor its combat heroes has no honor.