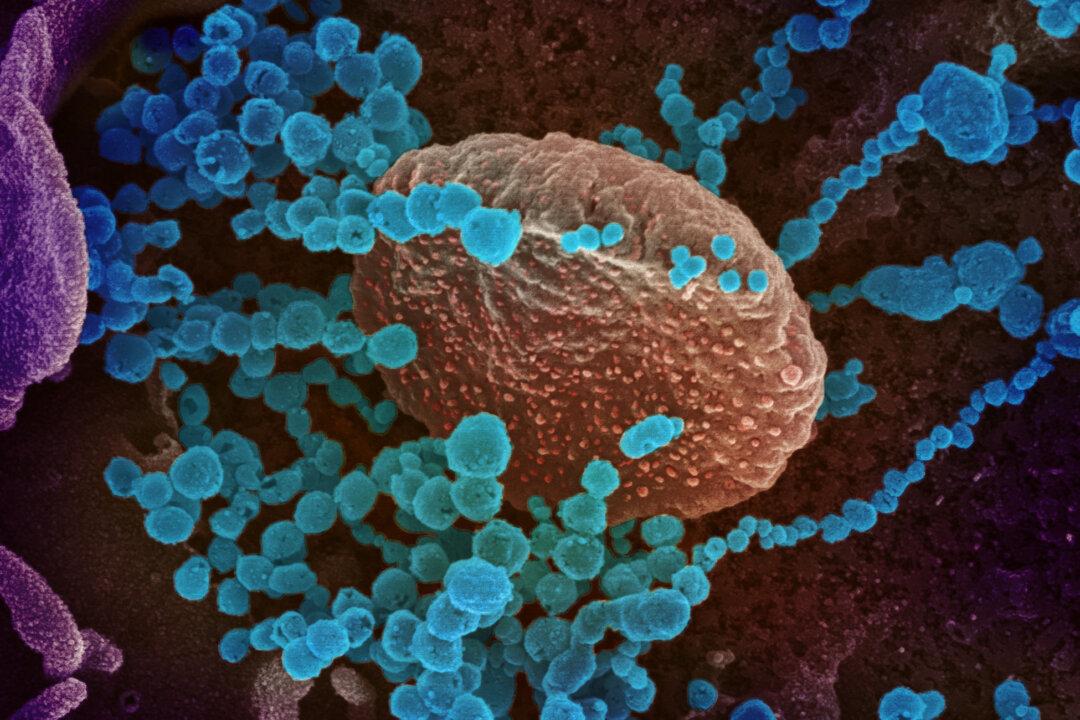

A new study (pdf) indicates that the CCP Virus could cause a patient’s immune system to attack the tissues in their own bodies.

The study, which was recently released as a preprint on Oct. 23, has yet to be peer-reviewed.

The study, which was recently released as a preprint on Oct. 23, has yet to be peer-reviewed.