Commentary

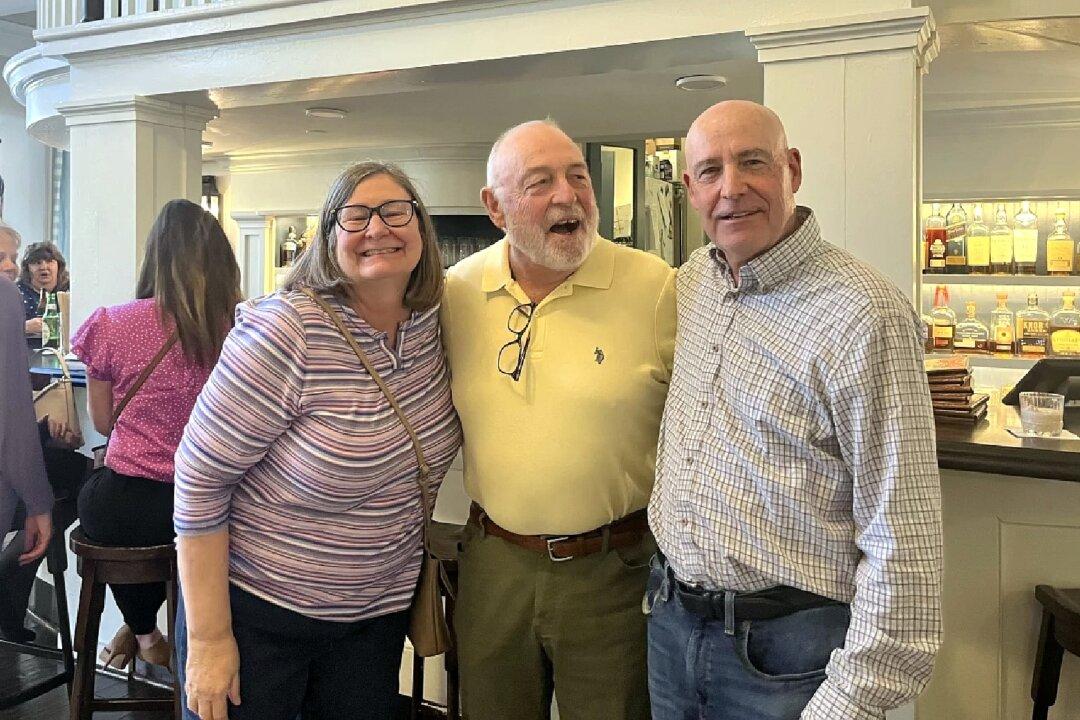

BEDFORD, Pennsylvania—From across the curved chestnut bar in the sprawling lobby of the Bedford Springs Hotel in this central Pennsylvania town, it was hard not to be drawn into the conversation between Christopher Ege, JoAnn Harrison and her husband, Dan. Given their animation and laughter, one might have assumed all three had known each other for years and clearly shared a lot in common.