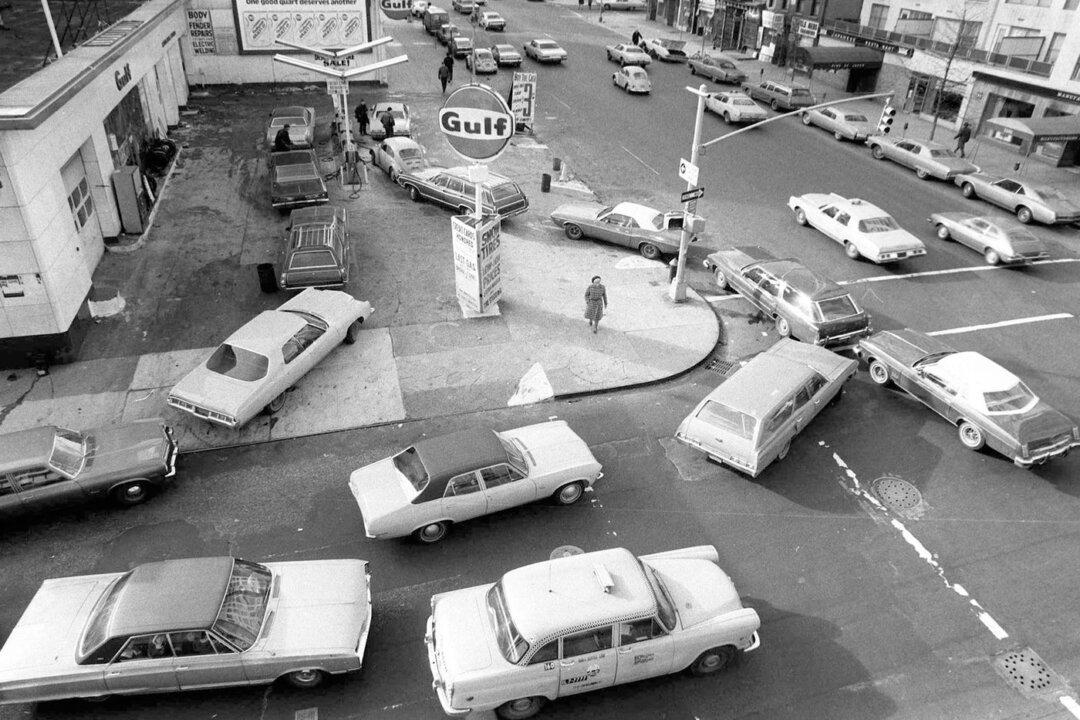

Canada is leaning toward a new era of 1970s-style stagflation as the pace of economic growth slows yet inflation remains stubbornly high, economists say.

The abnormal mix of rising prices and high joblessness gripped the country 40-odd years ago.

Canada is leaning toward a new era of 1970s-style stagflation as the pace of economic growth slows yet inflation remains stubbornly high, economists say.

The abnormal mix of rising prices and high joblessness gripped the country 40-odd years ago.