During his all-star career as a pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Steve Blass was a World Series hero, but the disease that ended his career is something many still want to ask about.

During a recent conversation with Mr. Blass during spring training at LECOM Park, the southern home of the Pirates, without intention, the conversation drifted to an all-too-common lane change.

Originally, Mr. Blass was providing a one-of-a-kind unique insight on some of the greatest players he shared a Pittsburgh clubhouse with for a decade. With former MLB skipper Jim Leyland heading to Cooperstown this summer as a member of the hall of fame’s Class of 2024, and with 11 of his 22 seasons piloting the Buccos in western Pennsylvania, this was as good as any starting point for comments from Mr. Blass.

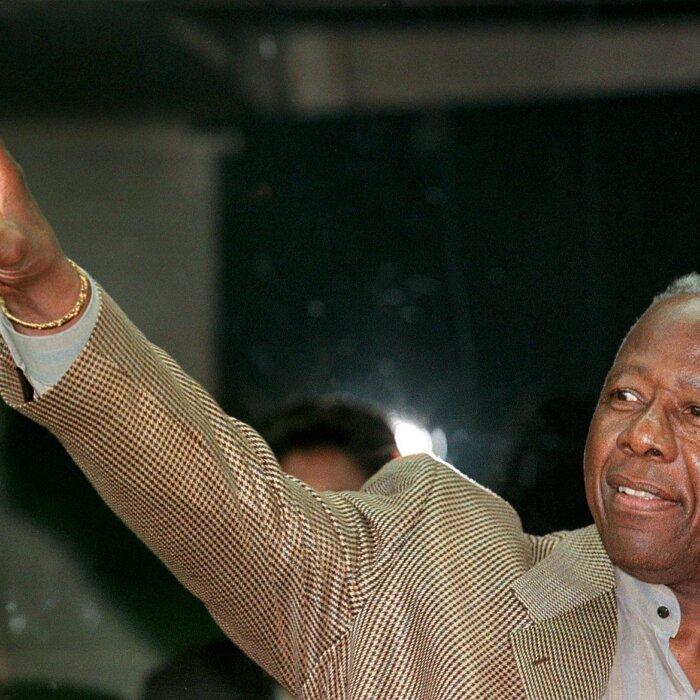

Employed by the Pirates now for 65 years, a business relationship that was planted in 1960 as a teenager signing with the club, then as a minor league pitcher, to being among the “best of the best” National League hurlers, to working in the club’s broadcast booth for 34 years. Today, Mr. Blass, 81, serves the Pirates’ universe as an ambassador; shaking hands at banquets, and waving to fans at minor league affiliates’ Opening Day festivities.

A reporter once said of Mr. Blass, he makes new friends feel like old friends. Any code concerning the former big leaguer rewrites as—they don’t come any nicer or genuine as the Canaan, Connecticut native.

After representing the Pirates’ alumni at an appearance prior to Pittsburgh hosting Tampa Bay for a Grapefruit League game, Mr. Blass seemed to have difficulty holding back the shear excitement he would share about the heights of a select few teammates that rose to the level of baseball eternity in Cooperstown.

Mr. Blass told The Epoch Times of having the highest respect for Mr. Leyland, both as a manager, and as a man.

A quick mention of the late Roberto Clemente really brought the happiest of times between the hall of famer outfielder and starting right-handed pitcher.

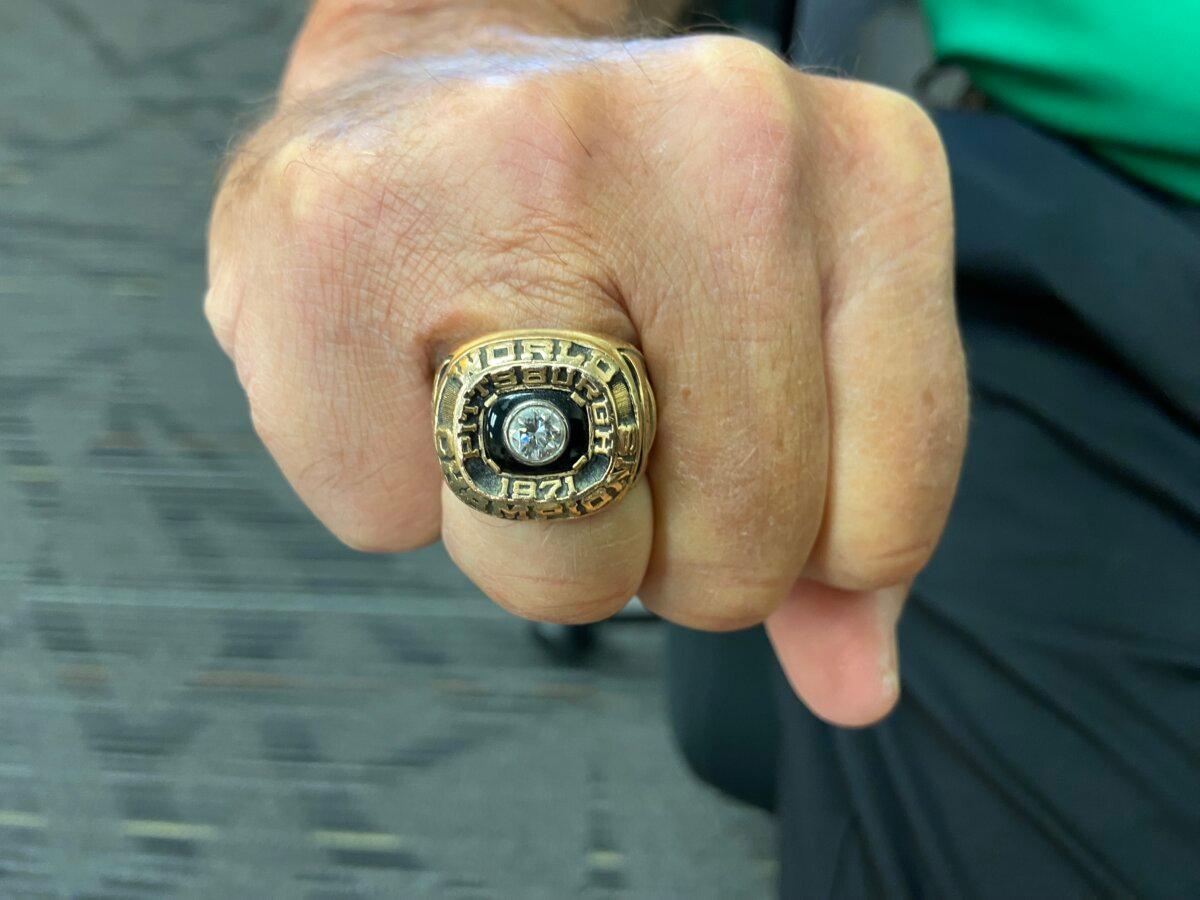

“In 1971, he [Clemente] was named the World Series MVP. I applauded him,” says Mr. Blass of the world championship that the Pirates won over the Baltimore Orioles. “When we were on the plane, ready to leave Baltimore, I was sitting with my wife Karen. Roberto walked down the aisle, and we embraced.”

To Mr. Blass, who shared Pirates’ clubhouses and dugouts with for eight MLB seasons with the popular Puerto Rican, Clemente will always be thought of as a teammate, friend, and his hero.

And when the subject of Mr. Clemente’s on-field greatness comes up for discussion, sadly, the day of his passing for many in the game remains burnt in their memories. While aboard a cargo plane filled with aid packages leaving his native Puerto Rico to an earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua on New Year’s Eve 1972, the plane carrying Mr. Clemente crashed. The “Great One’s” body was never found.

From the unexpected loss of his friend from Puerto Rico, when Mr. Blass is asked to give a memory of fellow Pirates’ World Series champion and who would one day join Mr. Clemente in Cooperstown, as expected, Mr. Blass isn’t short of smiles and stories.

“When I came up from the minors, I gained the greatest respect for Willie. He was more than a baseball friend.”

Then, there is hall of fame second baseman Bill Mazeroski whom Mr. Blass holds in the utmost respect.

Labeling the former Pirates’ infielder a “rock solid human” whom he learned a lot from as a ballplayer, Mr. Blass sincerely believes that Mr. Mazeroski should have been an automatic for Cooperstown. In 2001, nearly three decades since he last laced up his spikes in Pittsburgh, Mr. Mazeroski was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

‘Steve Blass Disease’

In 1975, when Mr. Blass walked away from the Pirates and the last thought of ever throwing a baseball again, just before the free-agency era was to take off, he knew there would be no changing his mind.“I walked off [McKechnie Field/now LECOM Park] holding each of my sons David and Chris’ hands, and I knew that I was done,” recalls Mr. Blass.

A pitching stud like Mr. Blass, who won two games in the 1971 World Series including throwing a complete Game 7 to silence the mighty Orioles’ bats of Frank Robinson and Boog Powell, suddenly, without warning, no longer could throw a strike.

“I couldn’t understand it. I was flying so high that it was as if I fell off a cliff. I still don’t know why it happened.”

The loss of physical and mental control of throwing a baseball with anything resembling accuracy was severe enough to coin the condition—“Steve Blass disease.”

For the Pittsburgh pitching ace, as he remembers, coming down with the disease, also known as the yips, was a gradual process. Winning 19 games in 1972, the following season, Mr. Blass looks back at starting with a 3–3 win-loss record.

“It wasn’t in a specific game that I can recall, but I figured down the road I’ll figure this out,” Mr. Blass explains of his loss of control on the mound. “The tough part was pitching at home, at Three Rivers Stadium. The fans were great to me. They never booed, but the silence in the ballpark was awful.”

Whereas sports, particularly in MLB circles, there is another medical condition, Tommy John surgery, that has become universally known and accepted. Back in 1974, Los Angeles Dodgers’ pitcher Tommy John enlisted surgeon Dr. Frank Jobe to perform what would be a career-saving operation of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction; stabilizing the elbow.

It’s a safe bet to say that more people, in and outside of sports, know the name Tommy John as a medical term, than the often-debated hall of fame left-handed pitcher’s statistics.

Nearly a century since baseball lost the great New York Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig to a progressive neurodegenerative disease known as ALS, for many, the mere mention of the hall of famer’s name, and a clearer understanding of the disease is understood.

Accepting the support of his then-manager Danny Murtaugh, Pirates’ ownership, his family, Mr. Blass left the game as a player he loved, but not on his terms.

Today, as a team ambassador, when giving tours of the Clemente Museum in Pittsburgh, or when representing the club at civic functions, it’s hard to believe that many of the conversations at the meet and greets don’t change lanes, then too, eventually taking the off-ramp to the “Steve Blass disease” exit.