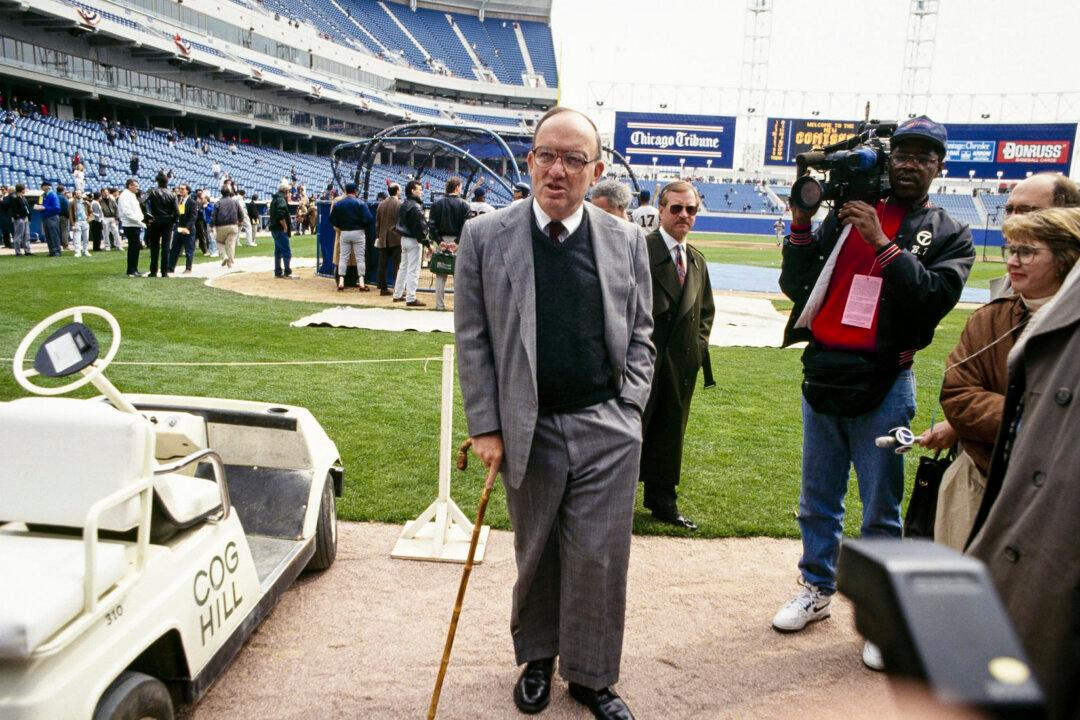

Fay Vincent has experienced his share of the ups and downs of Major League Baseball as a fan and commissioner.

There are those uniquely brilliant, wonderfully skilled storytellers whose conversations you hope have no time limits. You listen and learn. Respect, admiration, and, if for nothing else, inquiring minds can’t get enough of their life’s experience. Vincent is at the front of the velvet rope when it comes to baseball brilliance.