The traditional Chinese dance and music company, based in New York, is well known for the precision of its dancers.

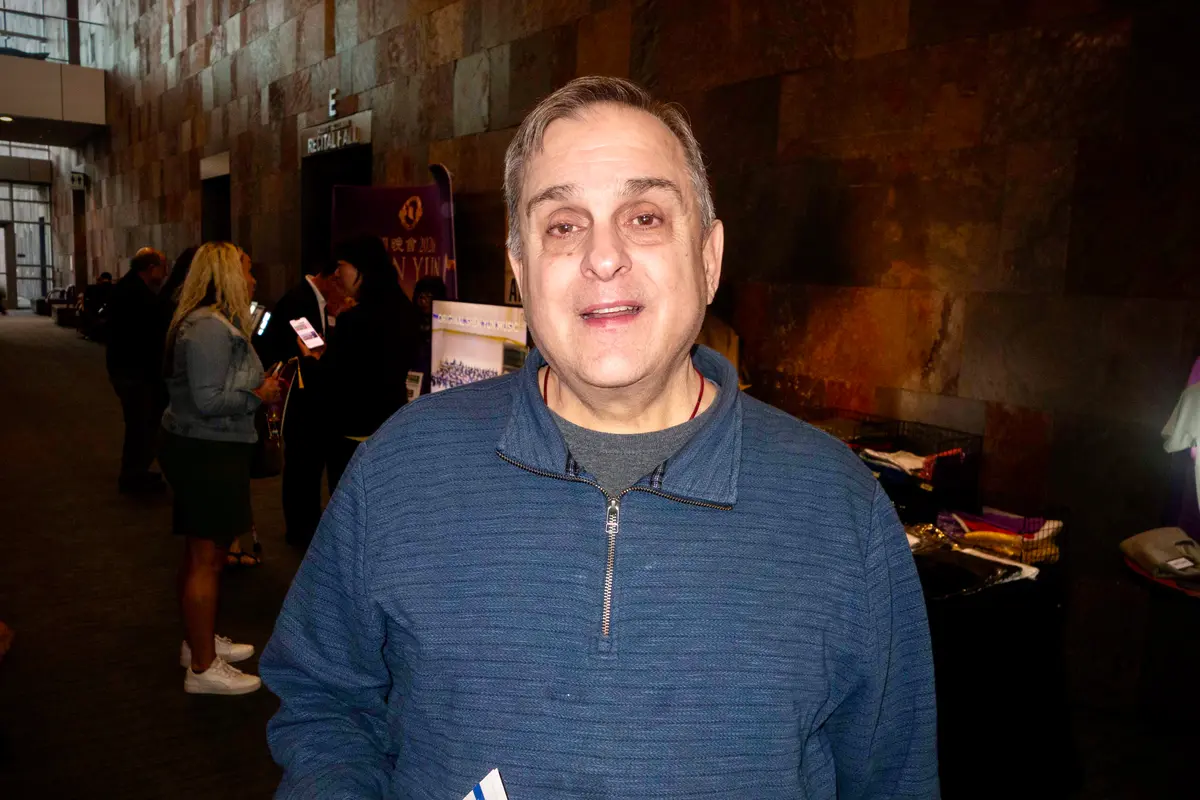

“We were talking about how impressed we are with the precision, with particularly the hands. I mean, it’s really quite breathtaking,” said Leckrone, who retired from his position as the director of the marching band at the University of Wisconsin-Madison just last year.

“He’s used to watching the marching ... like a halftime show,” said Sarah Marty, who accompanied Leckrone.

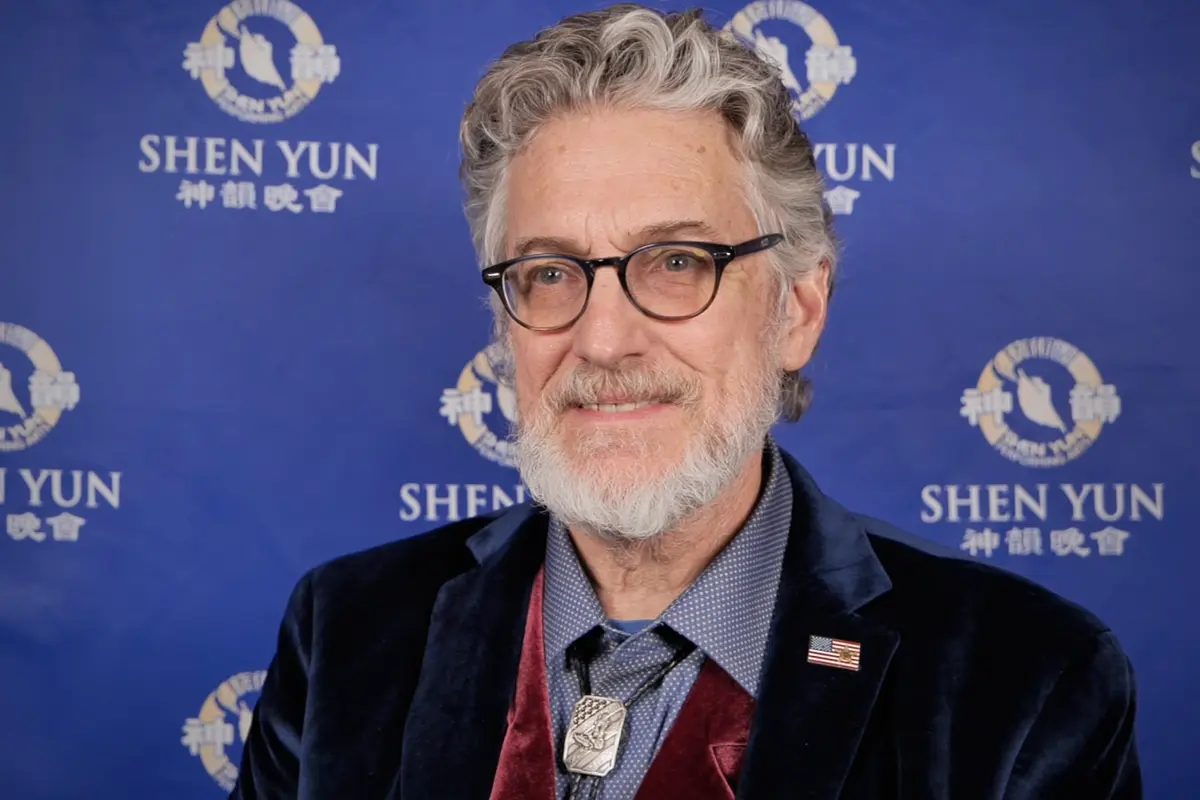

“With 250 [band members] and everyone has to be exactly perfectly together,” she explained. Marty is the director of the Madison Early Music Festival, a theater producer, and a professor, also at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“We didn’t know there'd be a live orchestra which was such a lovely surprise,” Marty said.

She’s seen what’s it’s like for dancers to have a live orchestra rather than a recording supporting them. “The music breathes with the dancer and breathes with the story in a way that’s really special. So that was a treat to get here [and think]: ‘Oh my gosh! There’s a real-life orchestra!’” she said.

“It’s a new sound: ‘I don’t know that sound. What is that? I wish I could see what that instrument was.’“ Marty said.

For while it’s mainly a Western symphony that brings Shen Yun’s newly composed yet ancient Chinese melodies to life, there is something that’s blended with the Western instruments: the distinctive sounds of Chinese ones, like the delicate-sounding pipa and the 4,000-year-old erhu.

“They really blend together beautifully,” Marty said, “and it’s fun when you hear it. … I really think that’s fascinating.”

Leckrone, who is not only a musician and conductor but also a composer, also spoke about the orchestra’s blend of East and West.

“You don’t get that juxtaposition of one culture on the other. … They’ve done a very good job of not making one thing jump out at you as being totally isolated. It is a very nice blend ... That’s the thing that I hear.

“It’s surprising how well this fits together.”

Leckrone was also thoroughly impressed with the quality of the playing: “What I’m listening to is how technically this is a very good orchestra. ... And I mean, I’m listening to some of the intricate technical things, particularly with the winds. I think it is really good, really remarkable.”

The music and the dancing combine in another remarkable way: They are the bedrock for showcasing traditional Chinese culture. Each of Shen Yun’s 20 or so separate dances either tells a story—from history, legends, or literature—or reveals the character of China’s many ethnicities or regions.

Underscoring the profundity of Chinese culture, said to be divinely inspired, is the tone of the stories the dances depict—some dramatic and some comic. They run the gamut of human emotions.

Marty enjoyed them all and then, as a theater producer, tried to imagine the difficulties of creating such a production from scratch.

“It’s challenging to compose music. You have an existing story. You know the dancers that you have; you know, what their skills are; you’re trying to communicate in [a short time]—and most of the pieces are five to 10 minutes long. So how do you communicate that whole story through music that will support the dance that needs to happen and the evolution of storytelling together?”