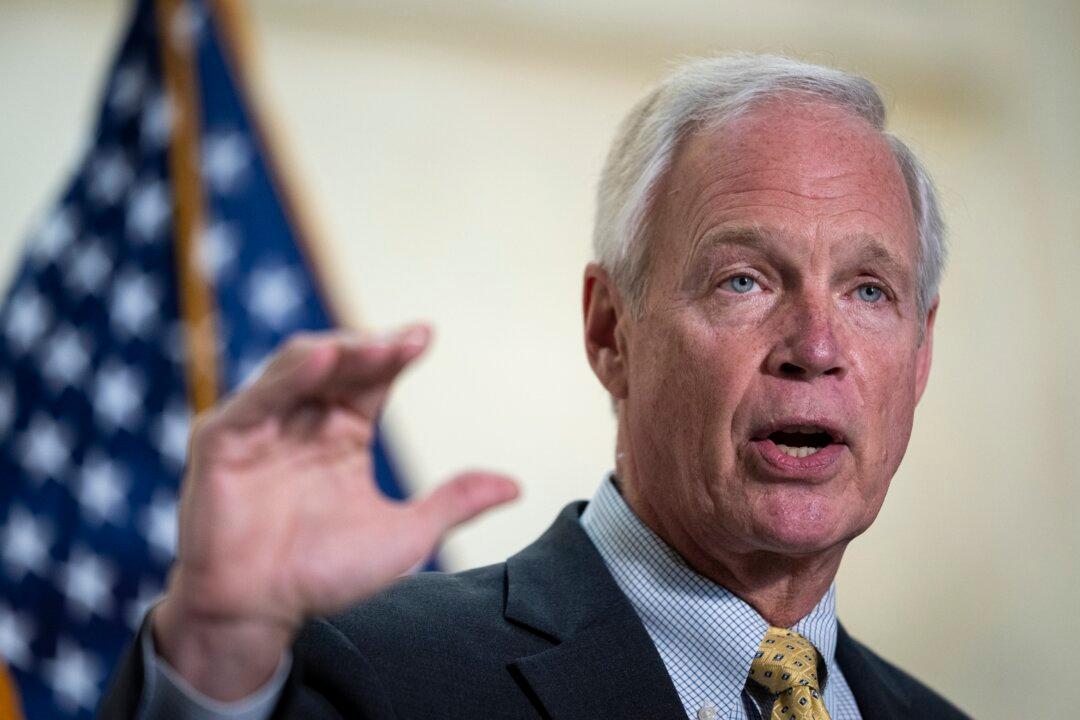

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) isn’t getting a COVID-19 vaccine for now because he still has high levels of antibodies against the disease.

Johnson and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) both contracted COVID-19, which is caused by the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) virus, last year.