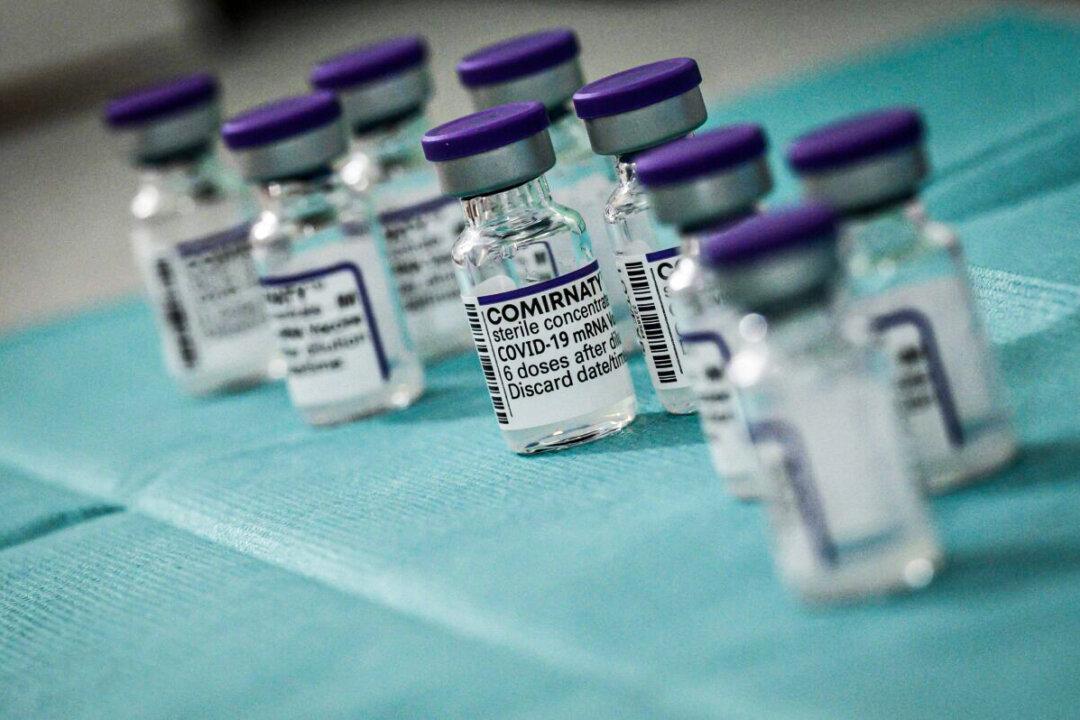

The protection provided by a second COVID-19 vaccine booster was worse than that bestowed by an initial booster, with the shielding trending negative after a period of time, according to a new study.

Protection against symptomatic infection was boosted to 64 percent for seven to 30 days after an initial Pfizer or Moderna booster when compared with the protection the person had from a primary series, researchers in France estimated. The measure is known as relative effectiveness.