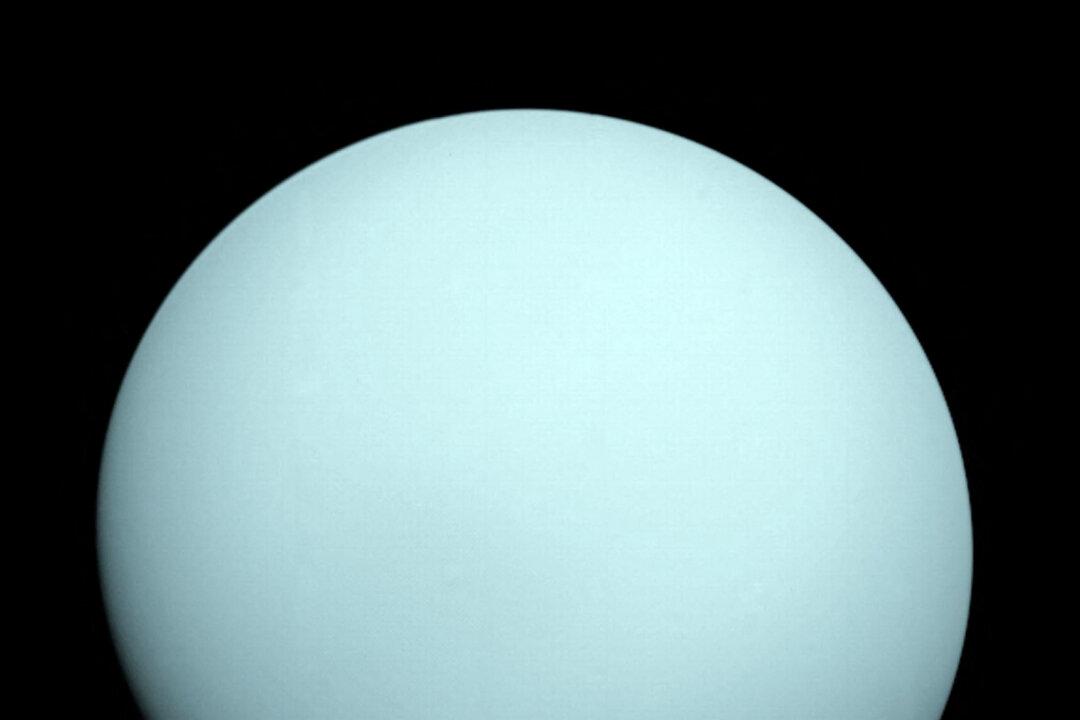

Scientists revisiting data from NASA’s Voyager 2 flyby of Uranus believe they’ve uncovered insights into a longstanding mystery, according to a Nov. 11 paper published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature Portfolio.

Voyager 2 space probe flew by Uranus in 1986, sending back crucial data that has shaped what scientists know about the planet. It’s still the only probe to visit Uranus and Neptune.