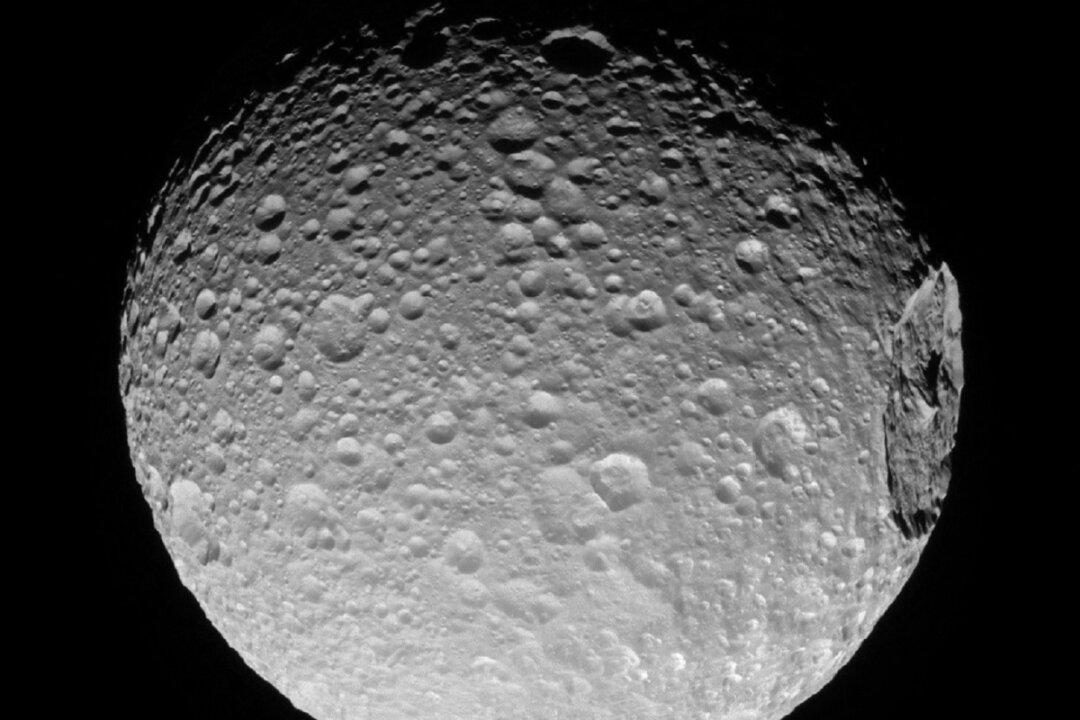

WASHINGTON—Saturn’s moon Mimas is known for its uncanny resemblance to the dreaded Death Star in the original “Star Wars” movie. But it has another intriguing distinction as well, according to researchers—a subsurface ocean hidden under its icy and crater-scarred outer shell.

Astronomers said on Wednesday that data obtained by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on the rotational motion and orbit of Mimas confirm the presence of an ocean of liquid water beneath an ice layer 12–19 miles (20–30 km) thick. This ocean, they said, appears to have formed recently, in cosmic terms—less than 25 million years ago and likely between 5 and 15 million years ago.