California researchers have predicted that by the end of the century, there will be an increase of up to 20 percent in tropical phytoplankton populations in low-latitude waters.

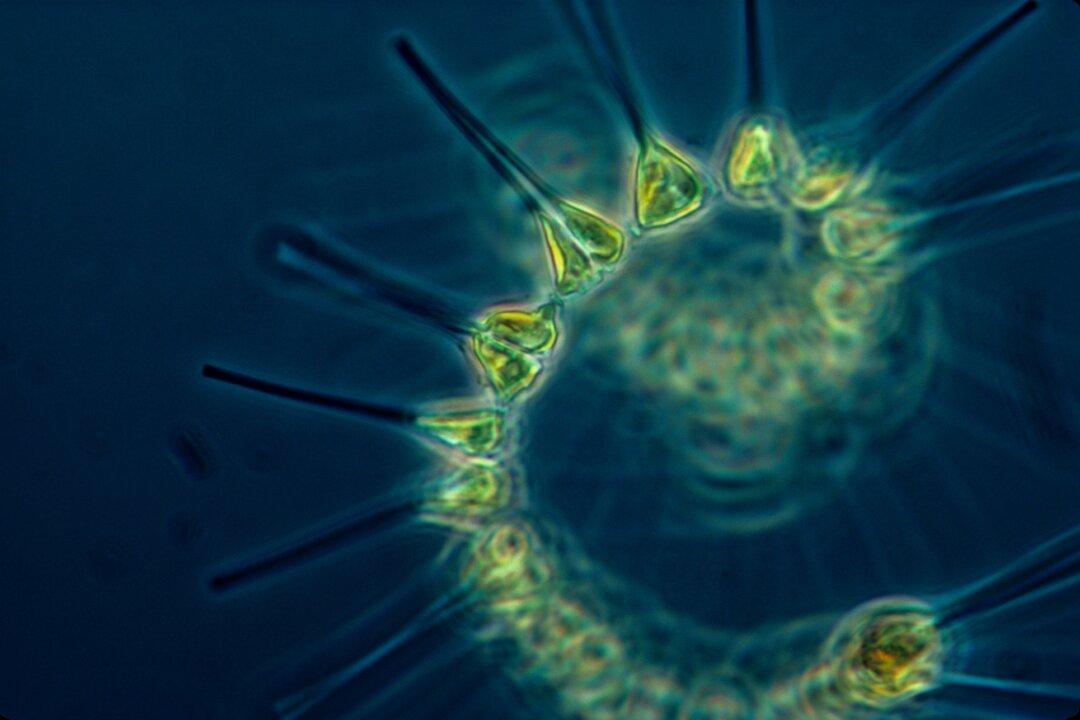

Using real-world data collected from a massive census of marine phytoplankton, or microscopic floating plants, to inform a neural network-driven Earth system model, oceanographers from the University of California–Irvine (UCI) made a surprising find that was published in the journal Nature Geoscience on Jan. 27.