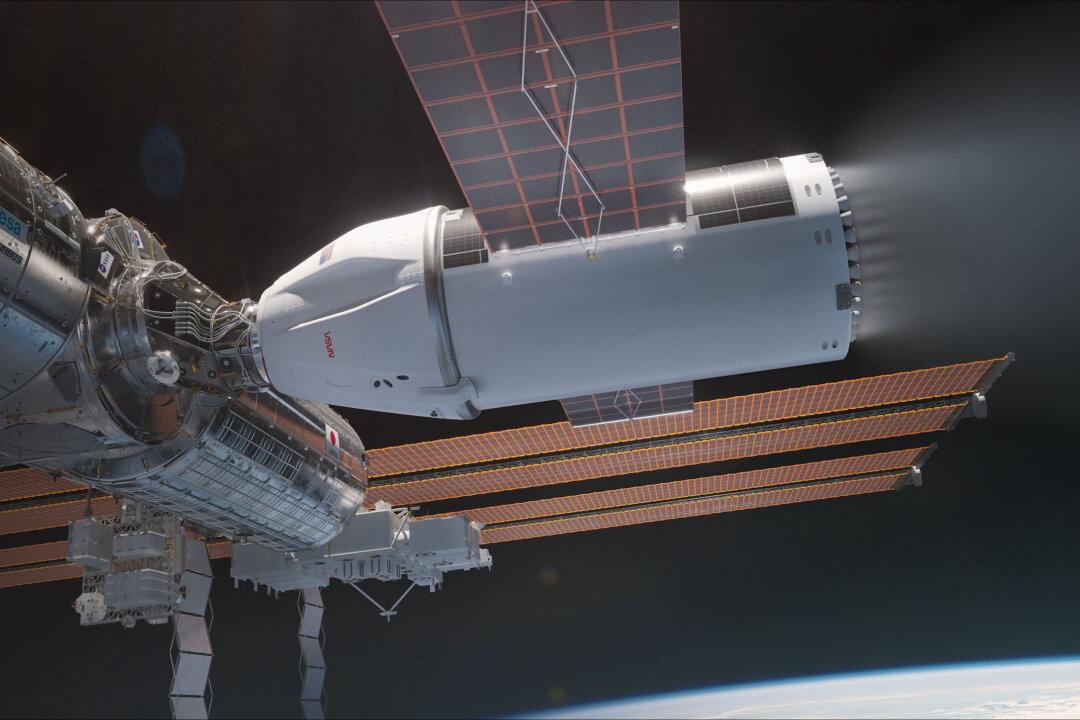

The International Space Station (ISS) is coming down.

NASA and SpaceX leaders announced their plan on July 17 to retire the ISS safely while maintaining an uninterrupted human presence in low Earth orbit.

The International Space Station (ISS) is coming down.

NASA and SpaceX leaders announced their plan on July 17 to retire the ISS safely while maintaining an uninterrupted human presence in low Earth orbit.