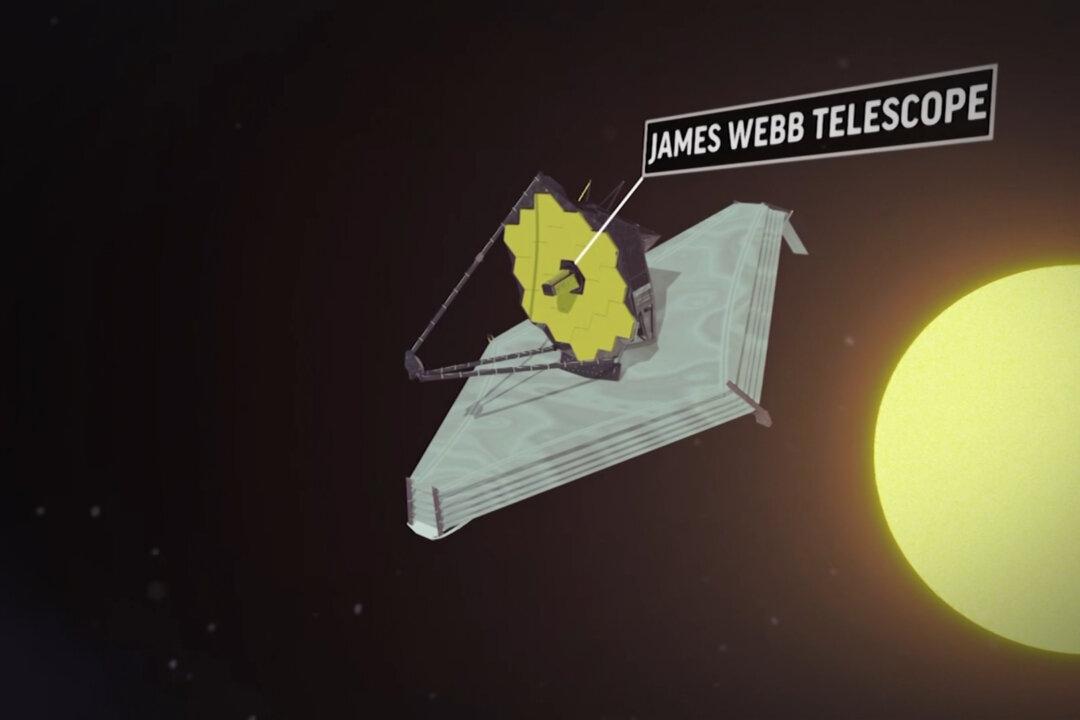

The Hubble Space Telescope’s heir is finally on the brink of flight.

It will be the biggest and most powerful astronomical observatory ever to leave the planet, elaborate in its design and ambitious in its scope.

The Hubble Space Telescope’s heir is finally on the brink of flight.

It will be the biggest and most powerful astronomical observatory ever to leave the planet, elaborate in its design and ambitious in its scope.