Commentary

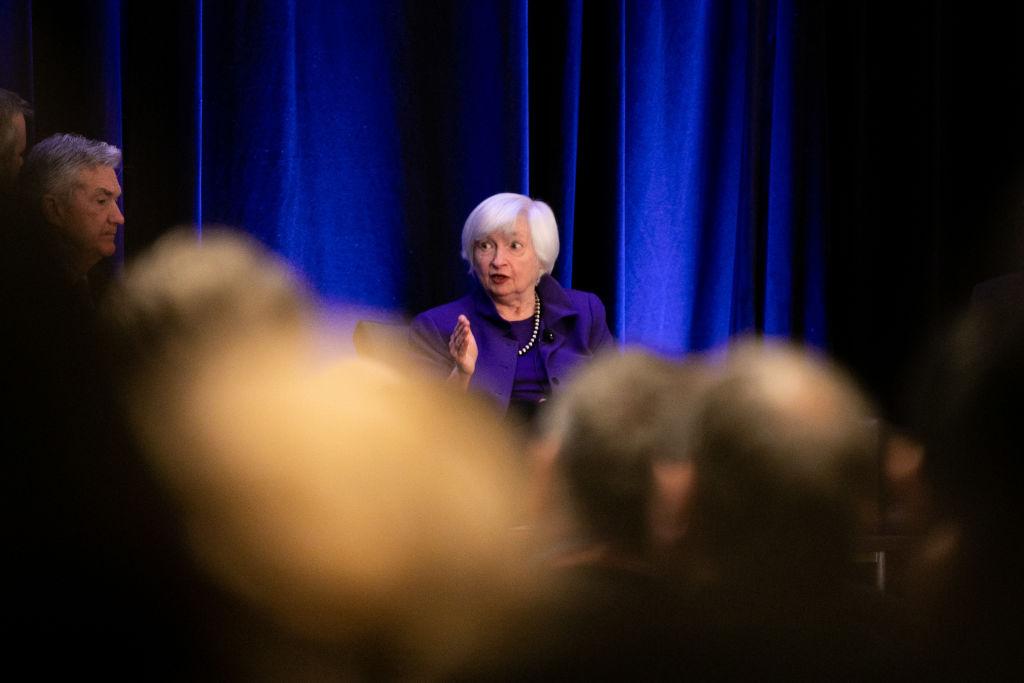

Something unusual and unexpected happened to me last week: I got an email from Janet Yellen, the previous chair of the Federal Reserve. At first I thought it might have been spam, but it was legitimate.

Something unusual and unexpected happened to me last week: I got an email from Janet Yellen, the previous chair of the Federal Reserve. At first I thought it might have been spam, but it was legitimate.