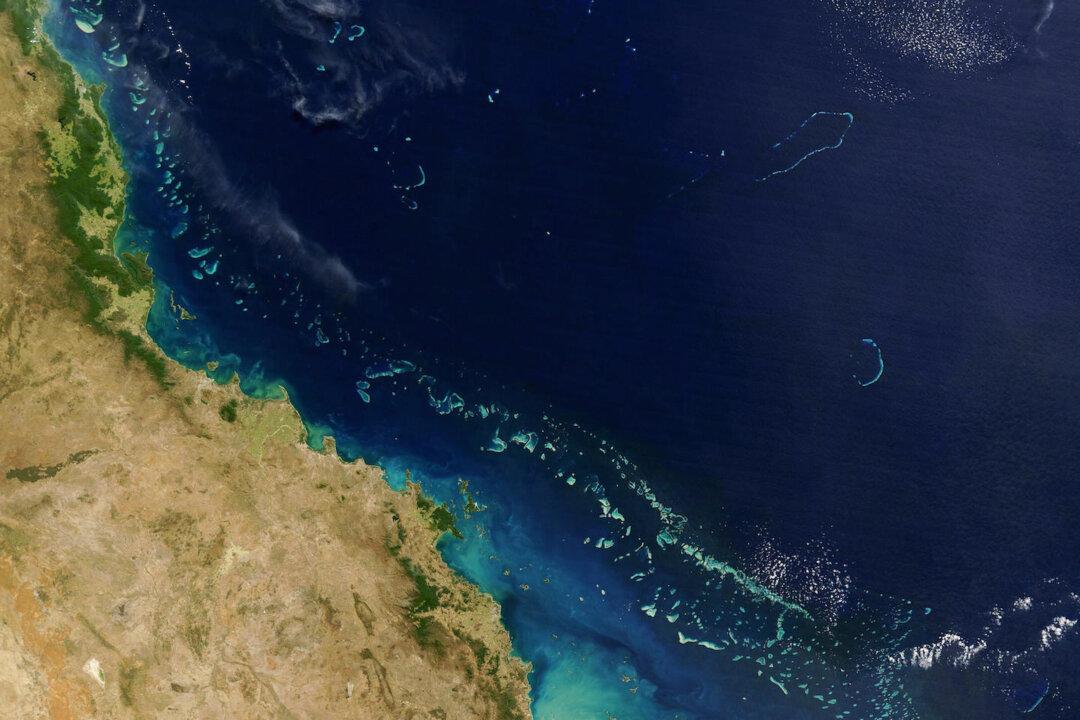

Satellite imagery is being used to help save Australia’s greatest natural wonder.

Researchers at James Cook University have developed a new technique employing NASA satellite images to analyse the impact of flood plumes in the Great Barrier Reef.

According to UNESCO, the Great Barrier Reef is one of the richest and most complex natural ecosystems in the world. It is home to 3000 coral reefs, 1050 islands and a multitude of different species of fish, mollusk and birds, according to government figures.

It is also one of the most extensive World Heritage listed ecosystems in the world, spread over 348,000 km2 - an area the size of Italy or Japan.

The Australian Government Reef Program aims to improve the quality of water entering the reef by enhancing land management practices, according to the university’s news release.

The researchers from the university’s TropWATER programme say flood plumes are the main way polluted water travels to the reef. They also say the main causes of flood plumes are heavy rains and cyclones, which scour mud and pollutants such as fertilisers and pesticides from land.

According to the university’s researchers, the traditional methods of monitoring flood plumes require scientists to gather water samples using boats or submerged data loggers. They say these methods are expensive, labour intensive and cannot be collected everywhere.

However, Dr Michelle Devlin, the project’s leader, says using satellite images can replace the need for costly traditional methods.

“These new monitoring techniques, with other ongoing risk assessments, will help prioritise how money can be spent to get maximum outcomes for the reef,” Dr Devlin said in a press release.

Dr Caroline Petus, a lead author of two studies that use the new technique, says the satellite images provide a long-term window necessary for understanding water quality inside the reef.

“These maps will help our understanding of the resilience of these ecosystems to water quality changes. In the near future they should help us predict ecosystems’ health changes associated with human activities or climate change,” Dr Petus said.