The impact of Russian disinformation on Canada was discussed during a House committee on April 5, with academics weighing in on the nature and scope of the phenomena. They didn’t all agree on its importance, but cautioned that government censorship could actually backfire by eroding trust in institutions.

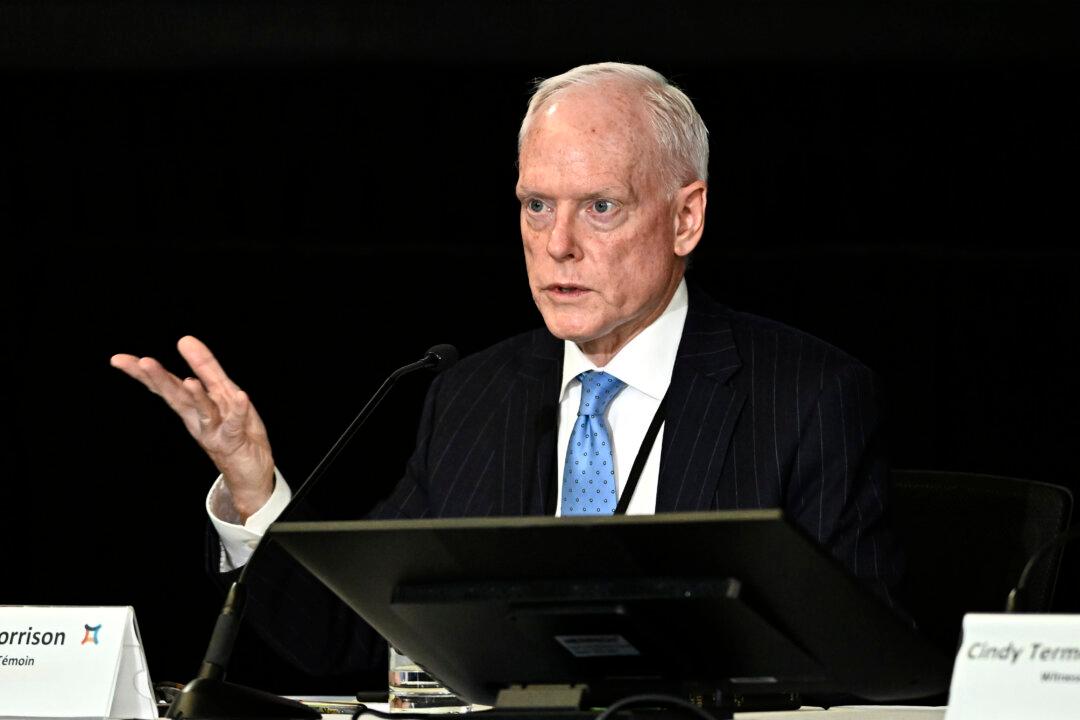

“In terms of disinformation, I’m not one who believes that Russian disinformation, or Chinese, or anyone’s disinformation campaigns really have much of an effect at all. I think that’s highly overblown and exaggerated,” said James Fergusson, deputy director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba.