Commentary

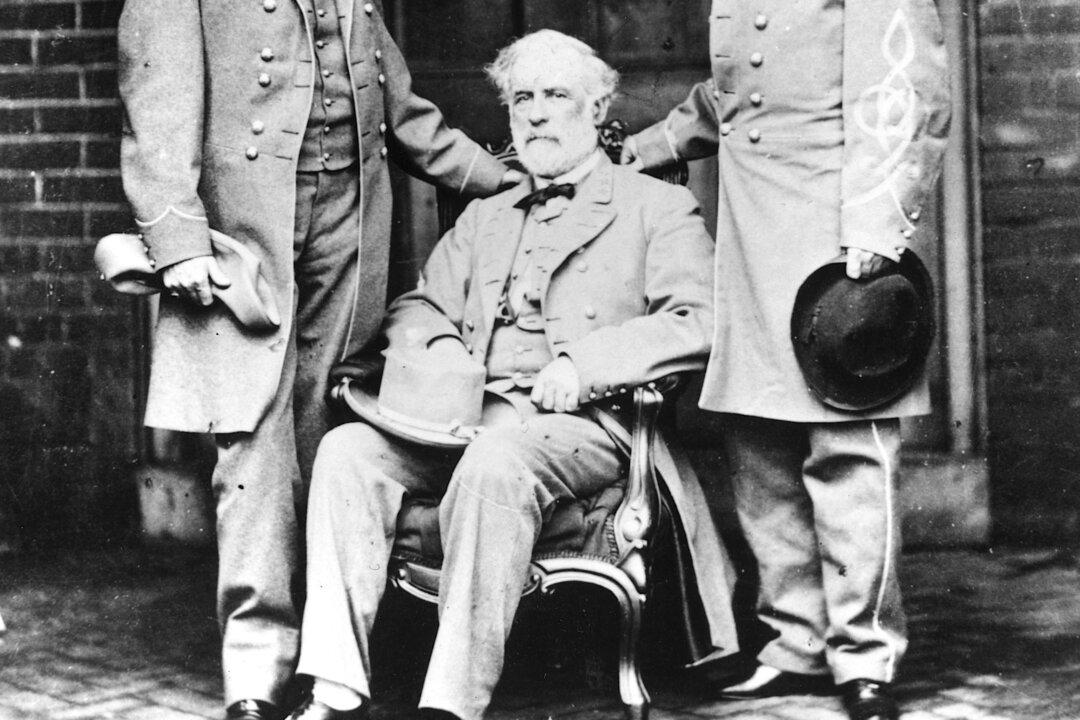

President Donald Trump committed another in his long list of supposed sins that progressive America deems unpardonable last week, when he publicly declared that Robert E. Lee was a great general. Use of the word “great” to describe any American even remotely associated with the Confederacy is absolute proof of racism among many Americans today.