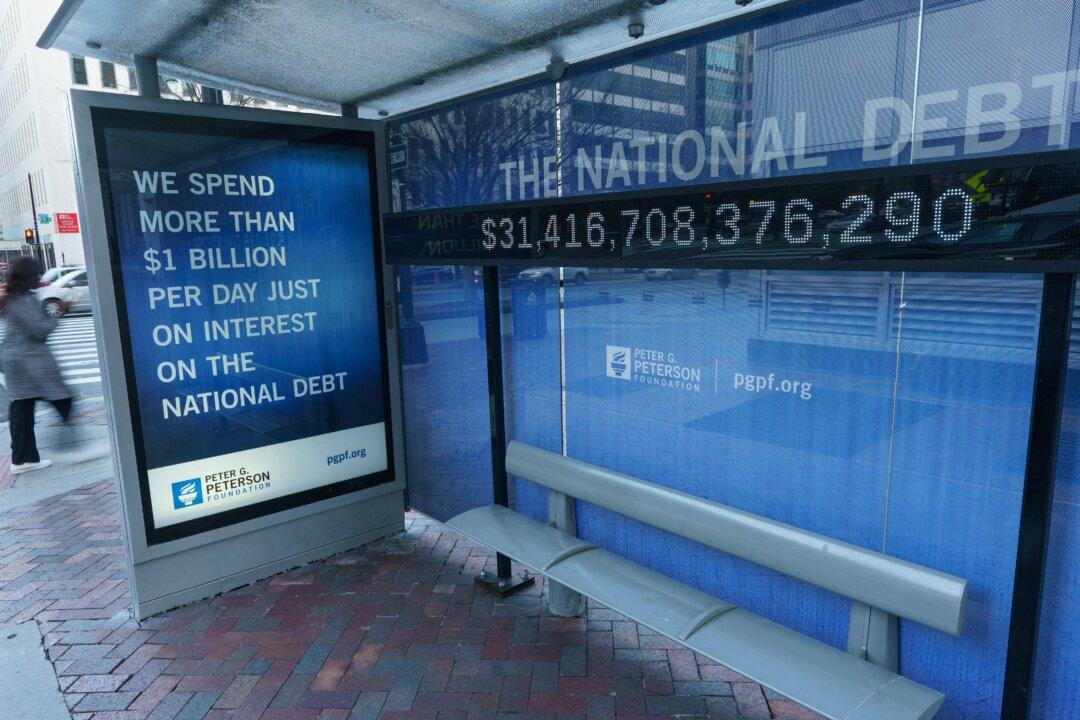

Stubbornly high inflation has kept the Federal Reserve on an aggressive rate-hiking path, driving up Treasury yields and borrowing costs, while reviving concerns about the sustainability of America’s nearly $32 trillion in national debt as interest payments rise.

Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell’s remarks on Tuesday and Wednesday before Congress—that the central bank might hike rates higher than previously expected due to persistent inflation—rattled markets and sent Treasury yields higher.