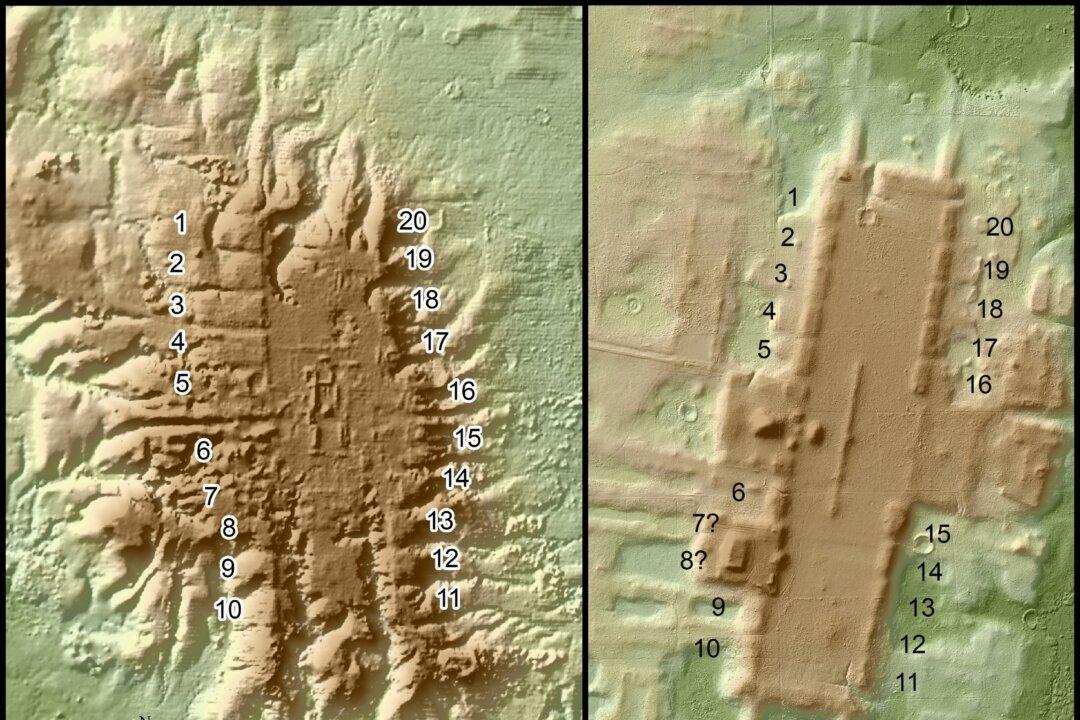

Aerial remote-sensing of a large region of Mexico has revealed hundreds of ancient Mesoamerican ceremonial centers, including a large one at an important site for the ancient Olmec culture that is known for its colossal stone heads.

The remote-sensing method, called lidar, pinpointed 478 ceremonial centers in areas that were home to the ancient Olmec and Maya cultures dating to roughly 1100–400 BC, researchers said on Monday. The study was the largest such survey involving ancient Mesoamerica, covering all of the state of Tabasco, southern Veracruz, and bits of Chiapas, Campeche, and Oaxaca.