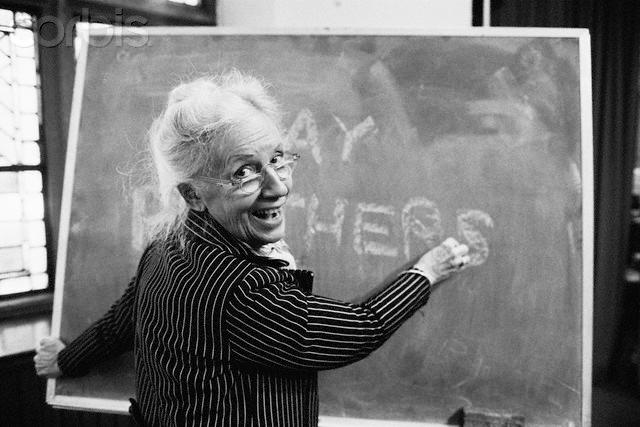

Hardly do clenched fists raised high in revolt invoke images of senior citizens. But in 1970, a recalcitrant Philadelphian named Margaret Kuhn started making waves in response to her forced retirement at the age of 65. Inspired by the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements, Ms. Kuhn set out to radicalize older Americans and fight the image of “old” as a dirty word that serves as a grim reminder of mortality.

Thus was born the Gray Panthers, a name she drafted from the Black Panthers, a radical movement in the 1970s.

Ms. Kuhn’s brand of activism fought ageism and a spectrum of topics relevant today latched onto by Millennials from universal health care to the elimination of nuclear weapons.

“The [aims of] Gray Panthers is not to be minimalized,” says Jack Kupferman, chairman of the New York Chapter of the Gray Panthers. “Our issues are central for the planet and for humanity.” To be sure, he stressed to the Epoch Times that the Gray Panthers is not just about education and awareness, but about creating change.

Ms. Kuhn, who died at the age of 89 in 1995, personified this vision, he says.

In the 1996 publication “Heroes of Conscience: A Biographical Dictionary,” co-authors Kathlyn and Martin Gay state that the Gray Panthers, which adopted the motto “Age and Youth in Action,” advocated that young people are as pertinent to the movement as seniors.

“There is the myth that stereotypes old age as a disastrous disease which nobody wants to admit to having,” Ms. Kuhn once asserted in an interview with Ken Dychtwald, a noted gerontologist and author. “Old age is not a disease—it is strength and survivorship, a triumph over all sorts of vicissitudes and disappointments, trials and illnesses.”