The RCMP is currently investigating reports of unauthorized Chinese police stations in Toronto, the national police force has confirmed to The Epoch Times.

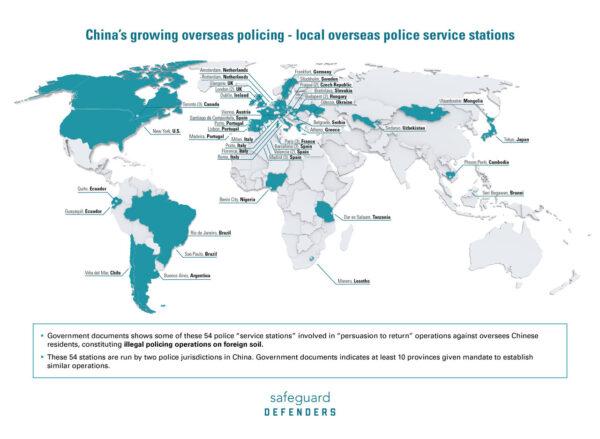

The report said that the stations, also known as “110 Overseas”—named after the emergency police phone number in China, “110”—have been used to support another campaign by the Chinese regime aimed at fighting telecommunications fraud allegedly conducted by Chinese living abroad, with Beijing touting the campaign’s success in “persuading” about 230,000 Chinese to “voluntarily” return to China to face criminal proceedings between April 2021 and July 2022.

Safeguard Defenders, however, said the campaign also targets non-suspects, and that the methods used by the police stations include intimidation, harassment, and threats against the target’s family members in China.

In an email statement to The Epoch Times, the RCMP said it is “investigating reports of criminal activity in relation to the so-called ‘police’ stations” in Canada, but declined to provide additional details of its ongoing investigations.

“The RCMP takes threats to the security of individuals living in Canada very seriously and is aware that foreign states may seek to intimidate or harm communities or individuals within Canada. It is important for all individuals and groups living in Canada, regardless of their nationality, to know that there are support mechanisms in place to assist them when experiencing potential foreign interference or state-backed harassment and intimidation,” said an RCMP spokesperson.

Any individual who felt threatened “online or in person” is encouraged to report the incident to local police or contact the RCMP National Security Information Network by phone at 1-800-420-5805, the email said.

The specific addresses of the three police stations in Toronto are provided in a Fuzhou government news release: one is in a convenience store in Scarborough, one is at a residential home in Markham, and the third is on a property that also serves as the headquarters of the Canada Toronto FuQing Business Association (CTFQBA), a federally incorporated non-profit.

The Epoch Times made multiple attempts to contact the CTFQBA for comment. Someone from the organization who answered a phone call didn’t respond to questions. Subsequent calls were unanswered.

“In most countries, we believe it’s a network of individuals, rather than ... a physical police station where people will be dragged into,” Harth said.

‘Sinister Goal’

In response to questions about the stations, the Chinese embassy said in a statement to CBC that local authorities in Fujian, China, had set up an online service platform to provide assistance to Chinese nationals living abroad, such as for renewing driver’s licences.“Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, many overseas Chinese citizens are not able to return to China in time for their Chinese driver’s licence renewal and other services,” the statement said. “For services such as driver’s licence renewal, it is necessary to have eyesight, hearing, and physical examination. The main purpose of the service station abroad is to provide free assistance to overseas Chinese citizens in this regard.”

The embassy noted that the overseas service stations are staffed by volunteers who are “not Chinese police officers” and are “not involved in any criminal investigation or relevant activity,” CBC reported.

But Safeguard Defenders said the overseas stations “both in their online and physical overseas form, also serve a more sinister goal as they contribute to ’resolutely cracking down on all kinds of illegal and criminal activities involving overseas Chinese,'” citing one incident, provided by the Chinese authorities, showing that the police stations have a role in the so-called “persuade to return” method.

On April 11, 2022, a police station within the jurisdiction of the Fuzhou Public Security Bureau received a notice from the overseas station in Mozambique saying that a Chinese businessman reported that one of his employees, a Chinese man with the surname Yang, had stolen a large amount of cash from his company before fleeing back to China in 2020.

“Upon receiving the notice, the police station immediately took to investigate and arrested the suspect on 18 May,” said Safeguard Defenders, citing a Chinese-language news release on the incident from the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission—an organization under the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) responsible for political and legal affairs.

Methods

Peter Dahlin, founder and director of Safeguard Defenders and co-author of the report, said in a previous interview with The Epoch Times that the report is part of its continued monitoring of China’s growing global transnational repression.Those operations target what Dahlin described as “high-value targets.” Officially, Sky Net says it only targets economic criminals and officials accused of crimes like corruption or bribery, according to the Safeguard Defenders report, but Dahlin said Sky Net has been found to also target human rights defenders.

Operations against high-value targets are run by the Chinese central police, whereas those involved in lower-level crimes like fraud—who are considered low-value targets—are tracked by the local Chinese police, he said.

“The most common method to do this is to persuade them to return ‘voluntarily,’“ he said. ”We’ve also had a number of cases where [Beijing] sent agents—Chinese police officers, undercover—to the target countries; we have a number of people in the U.S. being indicted for this.”

“Persuasion to return” is a method of the Chinese regime’s “involuntary returns” operations, which the report said entails either the “tracking down of the target’s family in China in order to pressure them through means of intimidation, harassment, detention, or imprisonment into persuading their family members to return ‘voluntarily,’” or directly approaching the target “through online means or the deployment of—often undercover—agents and/or proxies abroad to threaten and harass the target into returning ‘voluntarily.’”

A third way is to use kidnappings. Dahlin noted that his organization has identified 22 cases of kidnapping, though this method is rarely applied in North American or European countries, where the CCP does “a lot more [of] sending secret agents to intimidate people and that type of operations.”

He told The Epoch Times that in addition to the three known stations in Toronto, there are likely other unofficial Chinese police stations either existing or being established in Canada, though they have yet to be discovered.