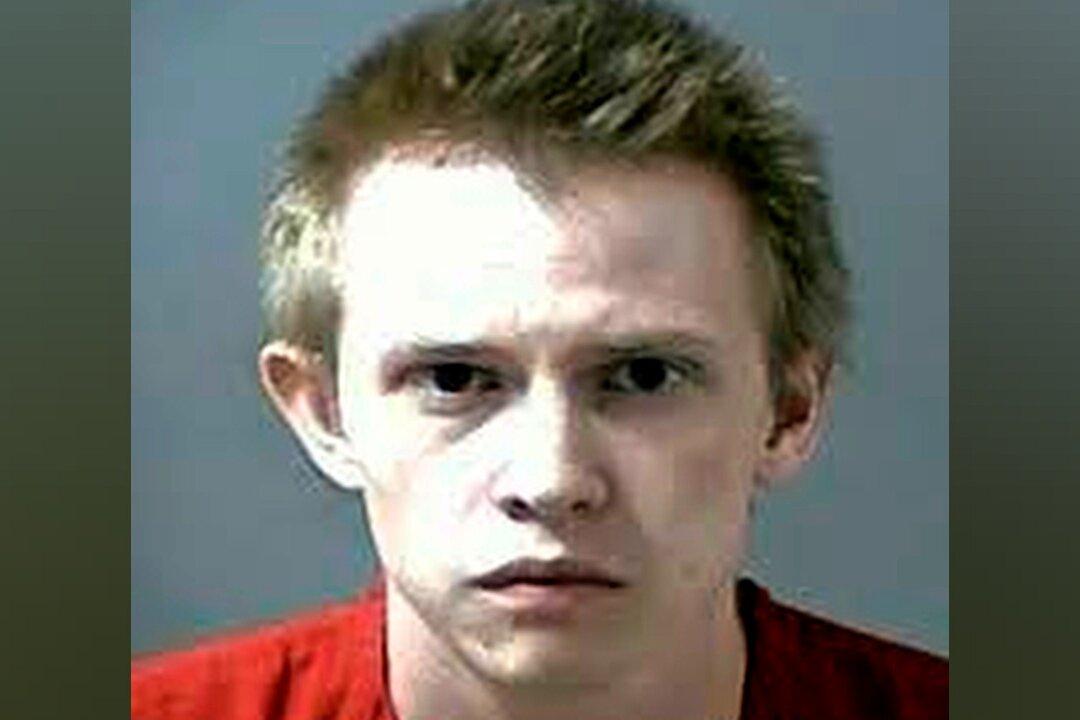

DENVER—Jeremy Webster got angry when a driver getting out of the way of an emergency vehicle almost hit his car, his outrage intensified by worry about getting into an accident since he wasn’t paying his car insurance bill. Webster followed the SUV, feeling like he was being directed by something outside of himself, a court-appointed psychologist testified Thursday at Webster’s murder trial.

Webster has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity to shooting the driver of the SUV and two of her sons, killing one of them, a 13-year-old, with a point-blank shot to the head after they pulled into the parking lot of a suburban Denver dental office in June 2018.