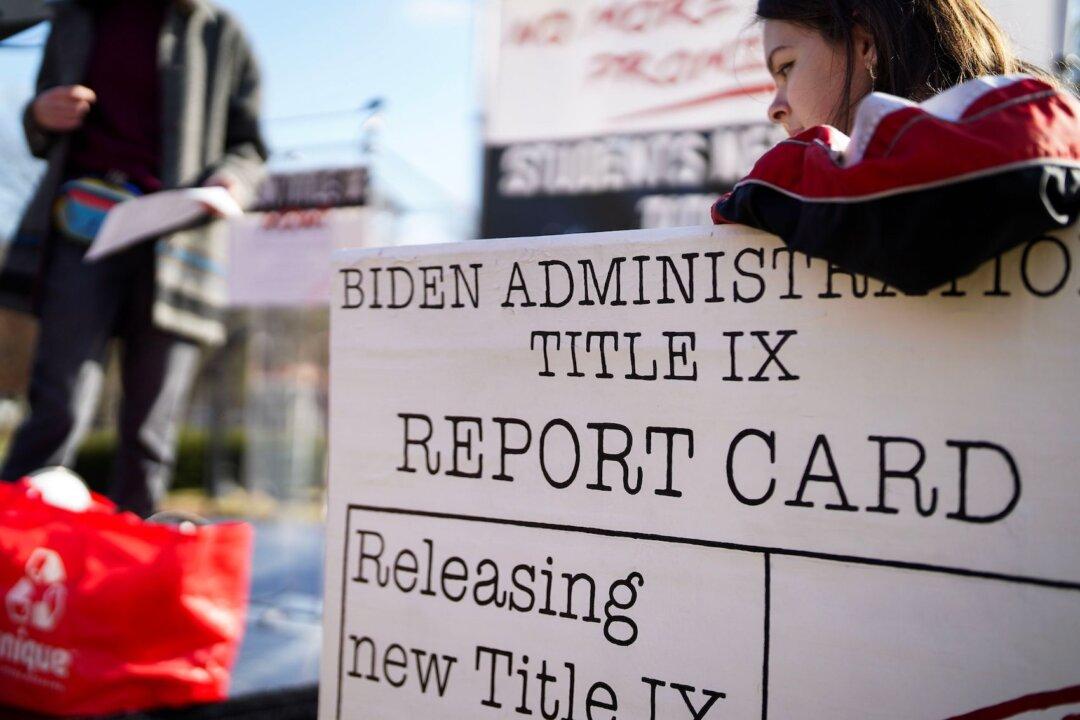

Commentary

What’s more democratic: the Supreme Court imposing a controversial abortion right on the entire country or the Supreme Court allowing that contentious issue to be debated and ultimately decided by the people through their elected representatives or voter referenda? Obviously, the people deciding for themselves is the more democratic option.