Commentary

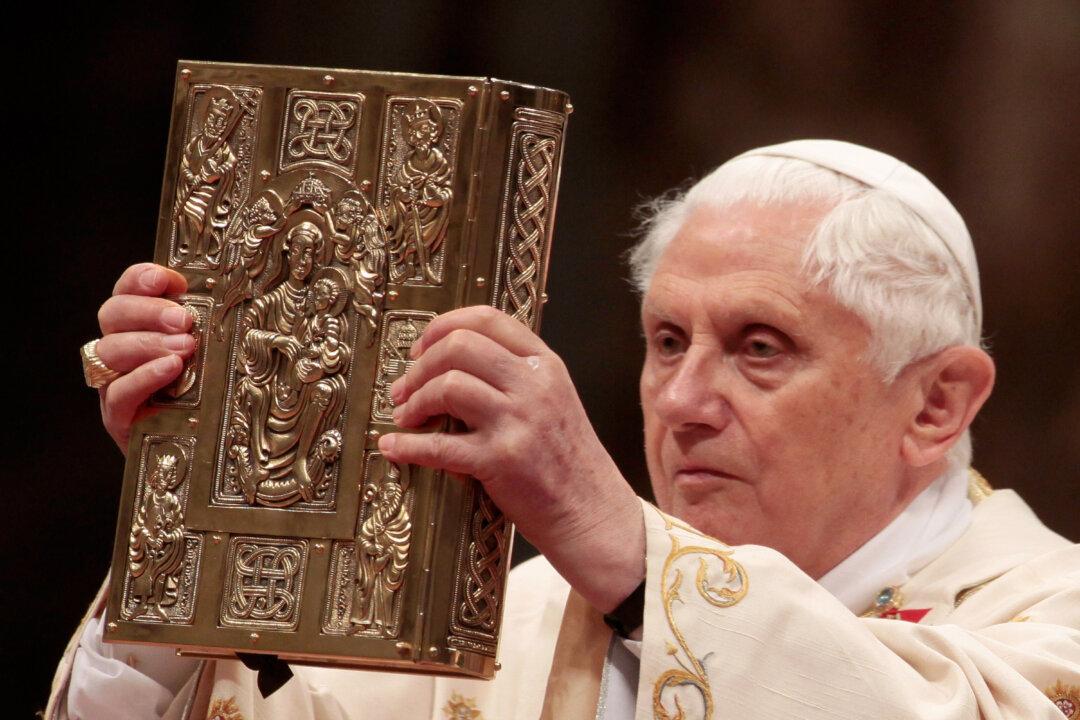

The resignation of the Pope in 2013 was a decision that completely shocked the world, partially because for a traditionalist like Benedict XVI, it seemed like a highly untraditional thing to do. But as head of the Holy Office in the last years of the previous pontificate, Cardinal Ratzinger watched with deep pain as the great pope declined in mental power and therefore managerial skill. The crowds grew as he traveled the world but there was a growing crisis developing within the church that only grew worse each year.