Within days of the announcement of a major Chinese Communist Party political meeting, the punishment of half a dozen high-level officials associated with the rival political faction was publicly announced.

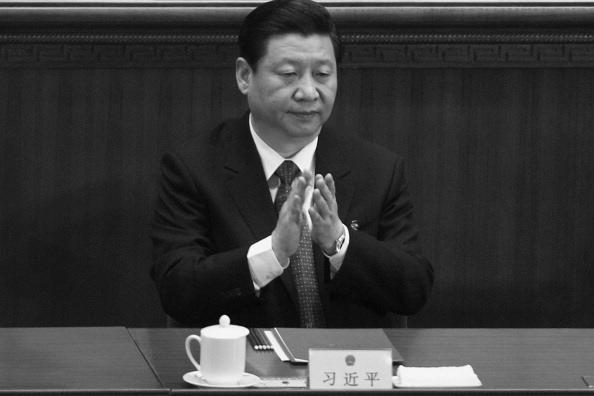

The “Fifth Plenary Session” of the 18th Congress of the CCP, as it’s called, looks to be a watershed for the regime leader, Xi Jinping, to further entrench his control over the Party apparatus.

Typically the fifth plenary session of a Party Congress are used to announce the next Five Year Plan, a relic of the communist planned economy. This year’s plenary session is also expected to include this—though much of the focus in the lead-up to it has focused on politics, and in particular personnel issues.

Leader Xi Jinping is increasing his control in the Party in the context of the session in two ways: investigating and eliminating the loyalists of the political clan that ruled China for nearly two decades before he came to power, and bringing in his own men.

It is well known that the former process has been underway since late 2012, when Xi came to the helm of the Party. The military, the security apparatus, the state-run petroleum sector, the official media, and other sectors have all been purged of prominent officials known to be affiliated with either Jiang Zemin or Jiang’s closest cohorts.

Jiang assumed power in the Party in 1989. While he formally stepped down in 2002, he retained immense influence in the Party for the next decade, analysts say. This was primarily through the individuals he had promoted through the ranks and inserted into the Politburo Standing Committee.

With the biggest players who had dominated the military and security services already removed, the eliminations now seem a matter of “cleaning out the dregs,” as some Chinese-language reports in publications outside of China put it--removing high-ranking officials who were not the top leaders in Jiang’s group.

Officials targeted include: Li Dongsheng, the former head of the Party’s secret police force, the 610 Office, whose trial opened on Oct. 14; Jiang Jiemin, Su Shulin, and Wang Yongchun, all former top officials in the lucrative petroleum sector, close loyalists to felled security czar Zhou Yongkang, and recipients of hefty prison sentences ranging from 13 to 20 years; Li Chuncheng, a former security cadre and deputy Party secretary of Sichuan, where Zhou served as Party secretary in the early 2000s. Li was jailed for 16 years; Guo Yongxiang, Zhou’s political secretary in Sichuan, who was jailed for 20 years; and Ji Wenlin, another Zhou protege, whose trial also opened recently.

While little else is known about the personnel movements around the Fifth Plenary Session, the meeting has often been a forum for major personnel movements.

Speculation is consistent that General Liu Yuan may receive a promotion. Liu, like Xi Jinping, is a so-called “princeling,” i.e. the son of a revolutionary leader. Liu has also been a public supporter of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign in the military, and is believed to have provided some of the early intelligence used to remove Gu Junshan, a lieutenant general who headed the pork-barrel logistics department and was a protege of Xu Caihou, one of two deputy heads of the armed forces who was since purged.

Chinese media report that since Xi Jinping has come to power, around 100 high-ranking officials—most with posts at least equivalent to that of a state governor in the United States—have been eliminated.

Zhang Zanning, a professor of law at Southeast University in Nanjing, China, said in a telephone interview with Epoch Times that the heavy sentences of these officials “are actually a fierce blow” by Xi Jinping to the overall political edifice constructed by Jiang Zemin, the former leader, and his followers.

Zhang referred to a recent series of leaks and coded messages in the Chinese press that also seemed to ridicule Jiang Zemin, and suggested that Jiang could likely become the final target for Xi Jinping’s purge. “Jiang’s crimes against humanity make one’s hair stand on end,” he said. “And Jiang’s family clan is the most corrupt in China.”

With reporting by Rona Rui and research by Jenny Li.