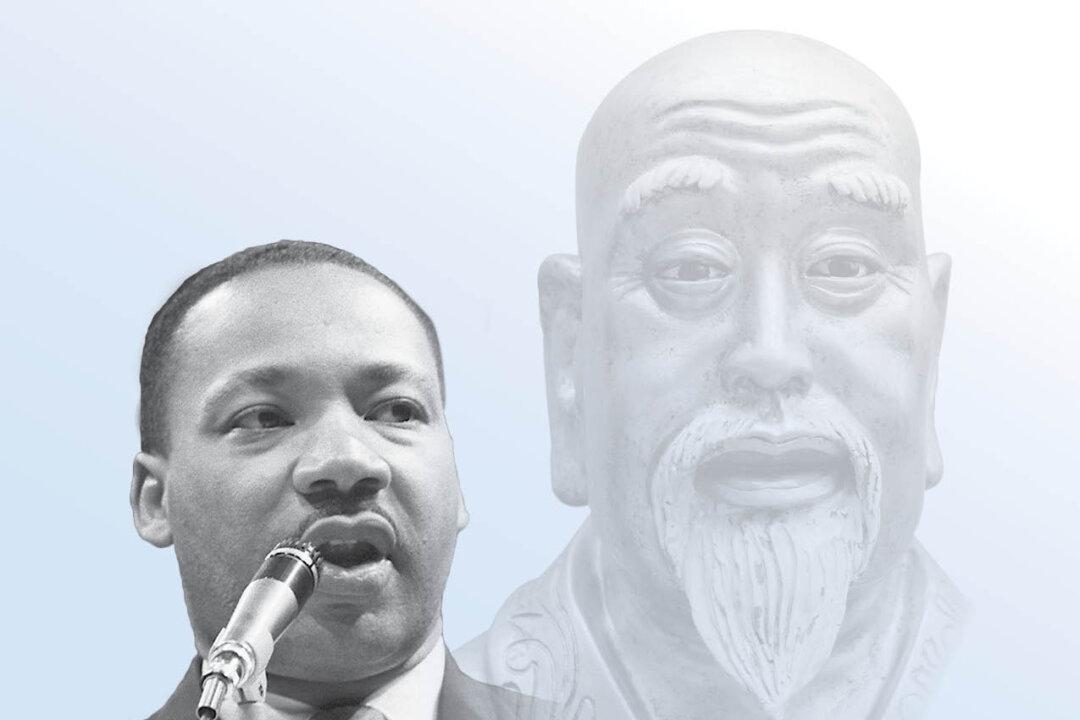

Since 1971, the third Monday of each January has been a U.S. federal holiday dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr., the great American civil rights leader. Today, he is remembered not just for his contribution to the civil rights movement half a century ago, but for the universal values reflected in his accomplishments and sacrifice.

“I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality,” King said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.”

For him, the path toward goodness and progress was a matter of conscious enlightenment.

Hundreds of years before Christ, in war-torn ancient China, the philosopher Mo Zi saw the same principles at work:

“Suppose we try to locate the cause of disorder, we shall find it lies in the want of mutual love,” Mo Zi said in his book of the same name “Mo Zi.”