Petitioners have to take their issues to the relevant office.

However, this petition system has evolved to become a part of the persecution machinery under the communist autocratic and corrupt bureaucratic system.

When the rights and interests of local residents are infringed on, they complain to the lower-level petition office following the regulations, but the issues are often negated there. The same situation happens at the higher level offices. Consequently, petitioners often resort to petitioning to the State Bureau for Letters and Calls in Beijing.

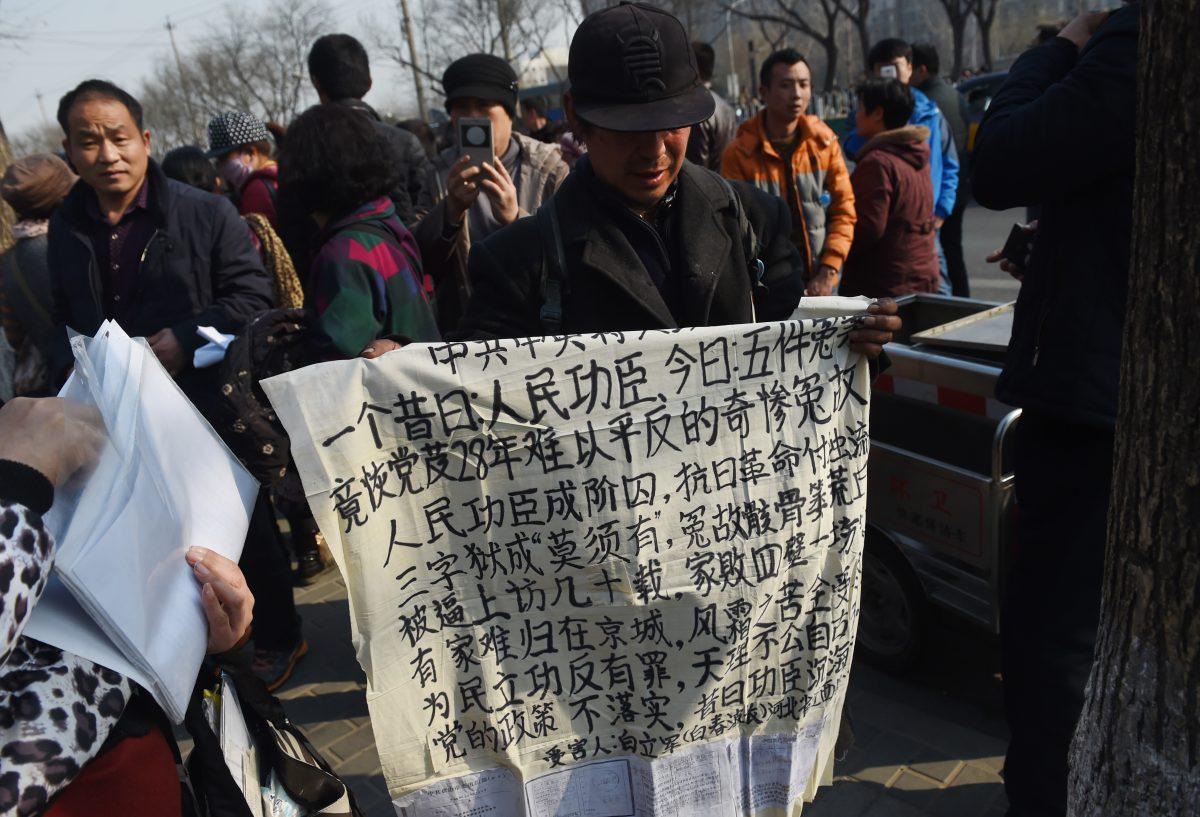

Mass Tragedy of Petitioning

Chen Jiangang was a Beijing human rights lawyer who is currently in exile in the United States. He told the Chinese edition of The Epoch Times, “There have been a large number of petitioners arrested, tortured, and abused. I have seen tragic cases where people were beaten to death because of petitioning. Stories like these are very many.”Local governments do everything to stop petitioners from going to Beijing, including having local police and thugs stationed in Beijing just to abduct the petitioners and take them back to their hometowns.

“Those thugs and hooligans from all over the country, provinces and cities, remove petitioners without any legal procedures,” Chen added.

He said, “People believe that someone in Beijing will listen, but this is [not] what they face in Beijing.”

Chinese dissident Dong Guangping explained that each petition is counted against the promotion of an official. Thus, local authorities strive to intervene in any type of petitioning to Beijing.

Unyielding Petitioners

Wu Yuxi, a villager from Hubei, an inland province of China, started petitioning when the local government deprived her of the right to receive financial relief after occupying her farm and home.On the evening of Aug. 29, Wu Yuxi was abducted from Beijing and taken back to Hubei. Local authorities kept her isolated in a quarantine site saying they did so because of the pandemic. That was the third time she has been detained since June.

On Aug. 31, Wu told the Chinese language edition of The Epoch Times, “We don’t like Beijing. Those tall buildings do not belong to us. The petitioners have lived in a slum and led a life of beggars. It’s worse than the beggars. We get packed into a vehicle by those thugs at any time. It’s becoming a part of our lives.”

She explained the hardships, “Our life is ruined, no job, and no income. My petitioning has lasted for 10 years. Others have even petitioned for 40 years. But none was resolved and no official explanation was ever given.”

She added, “I was told that only China has the Letters and Calls Bureau. We have the public security, procuratorates, and courts, from the local to the central level. If any of them abided by the law and constitution, and upheld justice for the people, no one would travel thousands of miles to Beijing to petition.”

She said that people were forced to start petitioning because they hit a dead end, “We endure great risks, we suffer the pain, but we are determined with unyielding strength against corrupt power; we still have hope.”

Wu Lijuan, another Hubei native, has been petitioning for 18 years after being unjustly laid off by a bank in Hubei. She has experienced numerous abductions, house arrests, detentions, reeducation through labor, and releases on bail.

On Sept. 28, she just escaped a local official’s attempt to abduct her while boarding a local train going to Beijing.

On Sept. 29, Wu Lijuan told the Chinese edition of The Epoch Times, “I have been illegally detained an average of three or four times a year. They put me under house arrest, in black jails, in legal classes, and motels. They booked the whole floor of the motel, more than a dozen rooms. They ate and drank, but I was isolated and beaten, … my wrist was dislocated from the beating, I’m already disabled for life because I didn’t receive prompt treatment.”

According to Lijuan, a window of her house was smashed, the door was sealed, and the internet cable line was cut multiple times. “This is what they will do to a woman. Rather than help to resolve my issue, they simply oppress my voice.”

Wen Jiabao Accepted Petitioner Complaints

It’s common to see petitioners from around the nation in a long queue outside the Letters and Calls Bureau in Beijing.

Jiujingzhuang and Majialou are two areas on the outskirts of Beijing notorious for the black jails established there. They are called “relief service centers,” and are entitled to deal with petitioners whom the authorities identify as irregular.

According to the regime’s definition, irregular petitioners mainly refers to people who appeal at non-designated places such as, Tiananmen Square, Zhongnanhai area, embassies and consulates, the residences of central leaders, and venues related to the Olympics.

As rumor has it, Jiujingzhuang for instance, could detain from thousands to tens of thousands of petitioners.

Black jails such as these are peppered throughout the nation.

In 2007, Yu Jianrong, a researcher for the Rural Development Institute, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, surveyed 560 petitioners in Beijing. The results showed 63.9 percent of them had been imprisoned or detained for petitioning, and 18.8 percent had been subjected to re-education through labor or sentenced to jail for petitioning.

Former Party leader Wen Jiabao is the only high-level official to personally meet petitioners at the State Bureau of Letters and Calls since the communists have ruled China.

On Jan. 24, 2011, Wen met eight petitioners at the State Bureau and demanded that the relevant officials investigate and resolve the issues. Chinese media Southern Weekly wrote, “This is the first time in 61 years.”

Letters and Calls Are a ‘Systemic Trap’

Speaking about the petition system, Wu Shaoping, a Shanghai human rights lawyer currently residing in the United States, told the Chinese ledition of The Epoch Times, “This is a systemic trap for petitioners and society.”He said, “To solve the problems created by the regime itself, to maintain so-called social stability, the regime created this internal petition system to resolve issues tht the judicial system failed to address.

“But the results have shown this system is nearly non-existent. It’s not intended to solve any problems, it’s just a tactic to exhaust both the time and money of the people.”

He used the demolition of residents’ houses as an example: when the corrupt local officials infringe on people’s rights and interests, how can one expect the officials at the same administrative level to supervise and solve the problems? The petitioners seek help from a higher-level authority, which often pushed it to the lower-level government. But, the number of petition cases affects annual performance assessments at all levels, which means the matters end up in a vicious cycle of no resolution. The petitioners only get drained from the long process of petitioning.

Wu also indicated that the petition mechanism actually gave rise to a profit chain to intervene in petitions.

“Usually, the higher level authorities notify local officials, who send people to intercept the petitioner’s visit,” he said, and there’s an allowance to cover the cost of each petitioner brought back to the local area.

Wu gave an example: if a petitioner is brought back from Beijing, the trip may cost $10,000 to $12,000. This expenditure is covered by the budget for maintenance of stability.

“They even book an entire motel, one whole floor or several rooms, just to detain petitioners. It’s become a chain of profit with some motel owners colluding with the interceptors.”

Wu said that after the chain of profit is formed, the local authorities deliberately create incidents requiring petition, and opportunities for petitioning and interception, “consequently, a group of people relying on the profit is formed.”

He said, “Those petitioners who hoped to change society could end up being put in a brainwashing center, detained, or sentenced on trumped-up charges such as disturbance of social public order, or picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

Wu believes that the regime’s petition system only serves to divert social conflict, and is in fact, a true dead end for petitioners.