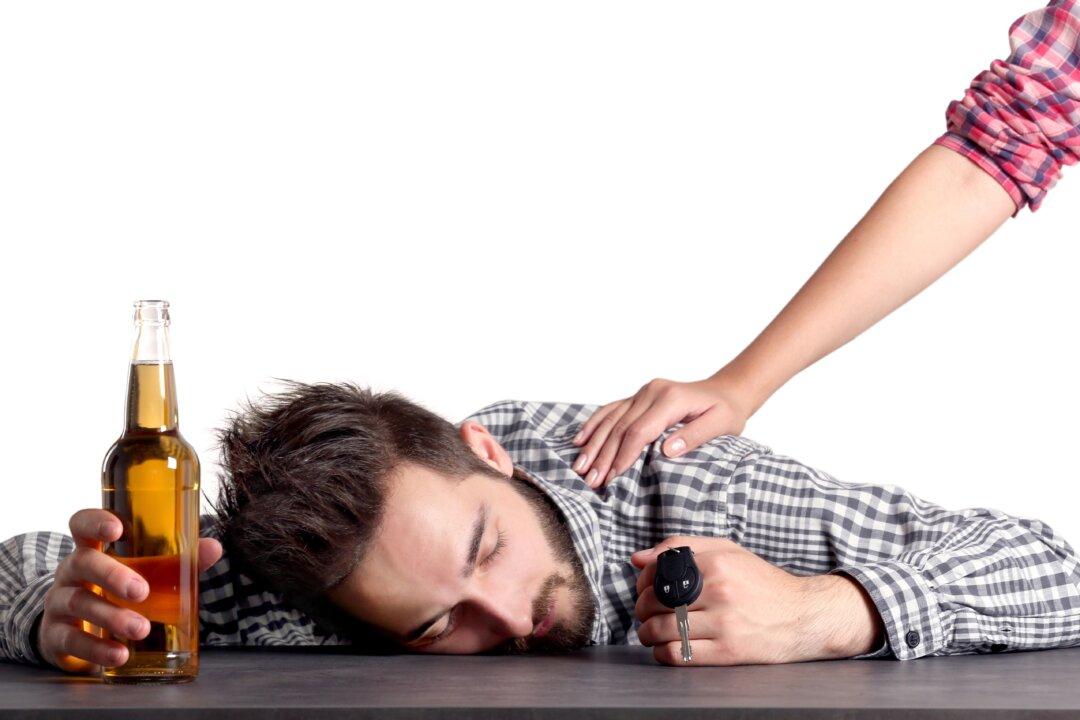

As the pandemic sends thousands of recovering alcoholics into relapse, hospitals across the country have reported dramatic increases in alcohol-related admissions for critical diseases such as alcoholic hepatitis and liver failure.

Alcoholism-related liver disease was a growing problem even before the pandemic, with 15 million people diagnosed with the condition around the country, and with hospitalizations doubling over the past decade.