Commentary

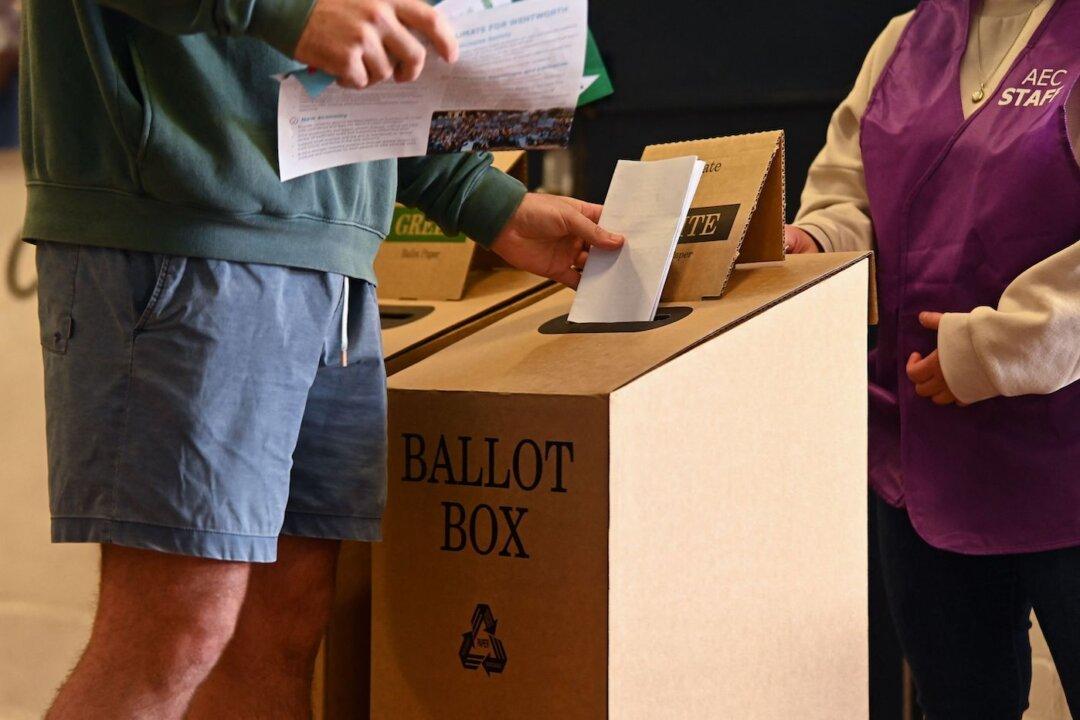

Australians can breathe a sigh of relief now that the federal election is behind us for another three years. Choosing who is going to be the next prime minister is one of the most important decisions a citizen of our country can make. And like any other decision, choosing one option invariably excludes choosing others. So it’s “either ... or.”