Ottawa sees a massive economic opportunity in creating a battery value chain for green energy and electric vehicles (EVs). Canada has a lot of what’s needed to gain a competitive advantage in this supply chain—the natural resources as well as research and industry expertise. Still, it has a long way to go to overcome challenges including domestic development of the required critical minerals, which are mainly controlled by China, two mining CEOs say.

Among the 31 critical minerals identified by Natural Resources Canada are key raw materials for batteries like lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and the rare earth elements (REEs), the latter best known for use in making magnets for electronics.

But in developing these minerals to build a battery supply chain, “It’s pretty hard to get an operation started until you can actually get a firm commitment on buying it, because these [critical minerals] are not bulk exchange-traded commodities, which is basically all the Canadian mining industry has ever been historically,” said Donald Bubar, president and CEO of Avalon Advanced Materials Inc.

He told The Epoch Times that in the two years since the announcement of the Canada-U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration, dependence on China has not been reduced significantly, mainly because domestic demand has not been created.

This is despite the feds recognizing that significant new investments in mineral production are required and that “China is the dominant controlling force for cell and battery manufacturing globally,” according to Canada’s 2020 Mines to Mobility report. The report is to serve as a reference for François-Philippe Champagne, minister of innovation, science and industry, as spelled out in his Dec. 16 mandate letter.

Bubar says mining for critical minerals should be looked at as a growth business starting at a modest scale.

“You don’t know how big your market is until you actually start to produce and get accepted in the market,” he said. “And then be prepared to scale up as you see more demand growth for the products that you’re able to recover.”

Bubar had previously suggested creating a stockpile of critical minerals with the government playing a key role in being the initial buyer. But he says the government, despite its ambitions, has never proposed such a solution.

Tracy Moore, president and CEO of Canada Rare Earth Corp., told The Epoch Times that a successful supply chain needs four basic pillars to work together—a good supply of concentrate, a refinery facility, customers to buy the majority of the output, and financing. He asked what Canada would even do right now if it were to produce REEs.

“You need all four basically, in my view, to come together simultaneously,” Moore said. “Only having two of the four cornerstones leaves a lot of work still to be done.”

His company sources and sells rare earth products but is currently focusing its mineral resource development, trading activities, and value-add facilities outside of Canada.

The powerful magnets made from REEs, for example, are not produced in North America. Businesses and consumers in North America are buying end products that already contain those magnets, typically made in China.

And Moore says his company prefers working with tailings since building a mine takes much longer than creating an operation to process tailings.

In 2021, Canada Rare Earth bought a massive stockpile of tailings in South America, which Moore says will take at least 12 years to process for REEs.

He says it is “low-hanging fruit,” whereas most of the projects in Canada that he’s aware of are hard rock and not close to large communities, which creates added logistical and cost issues.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) pointed out in a Dec. 8 blog post that a typical EV battery pack needs around 8 kilograms of lithium, 35 kilograms of nickel, 20 kilograms of manganese, and 14 kilograms of cobalt.

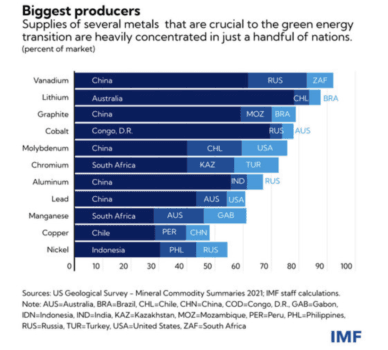

The IMF shows that supplies of some 11 minerals critical to green energy transition are concentrated in just a handful of nations and that Canada is not one of them. Canada is only the 6th largest producer of nickel and cobalt and the 11th largest copper producer.

Supply Lags Demand

The IMF reported that under a net-zero scenario, with the increased metals consumption, “current production rates of graphite, cobalt, vanadium, and nickel appear inadequate, showing a more than two-thirds gap versus the demand.”

Moore noted that the prices of REEs neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium have all increased significantly in 2021. Returns are reportedly anywhere from 50 to upwards of 100 percent. But given that these elements trade mostly in private transactions, price transparency is lacking.