Commentary

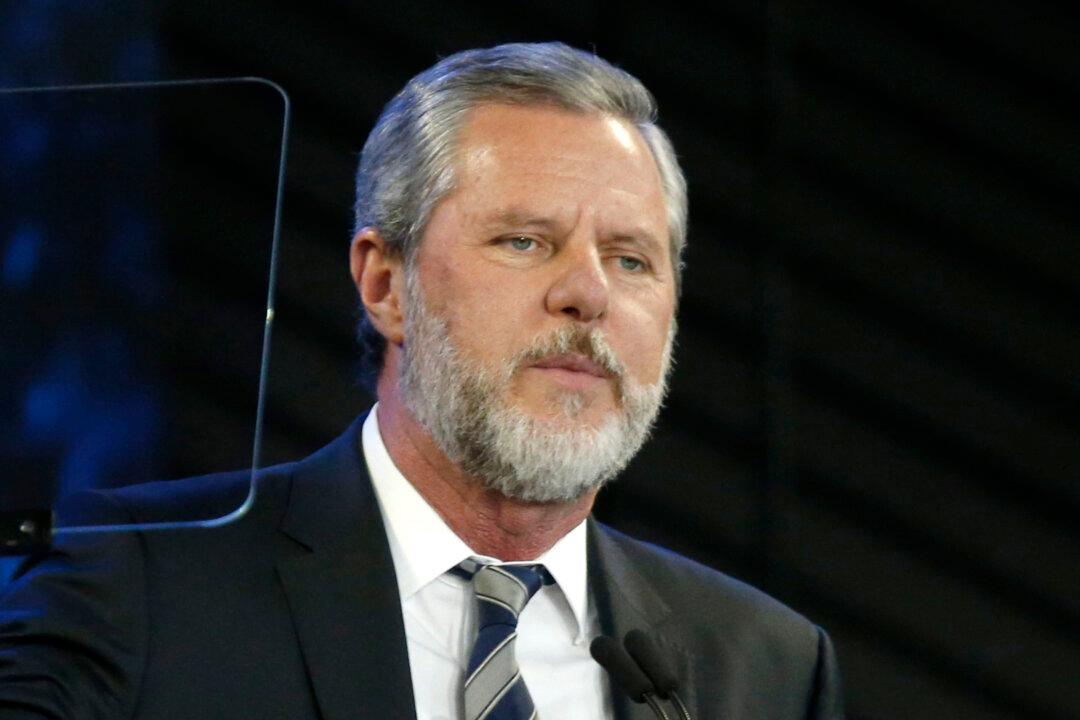

On Aug. 24, Jerry Falwell Jr. resigned as president of Liberty University, the Baptist school founded by his father, a major Evangelical figure.

On Aug. 24, Jerry Falwell Jr. resigned as president of Liberty University, the Baptist school founded by his father, a major Evangelical figure.