In an era where certain segments of the population have settled on the phrase “systemic racism” to describe all kinds of individuals, organizations, and even entire countries (some have called Canada itself systemically racist), it is hard to get any neutral, fact-based words in edgewise. That racism is an unfortunate part of our species, inherent in many people from many backgrounds (including different “racial” ones), is beyond dispute.

The process through which judges in Canada grant intercept warrants is a long one and involves several steps, writes Phil Gurski.

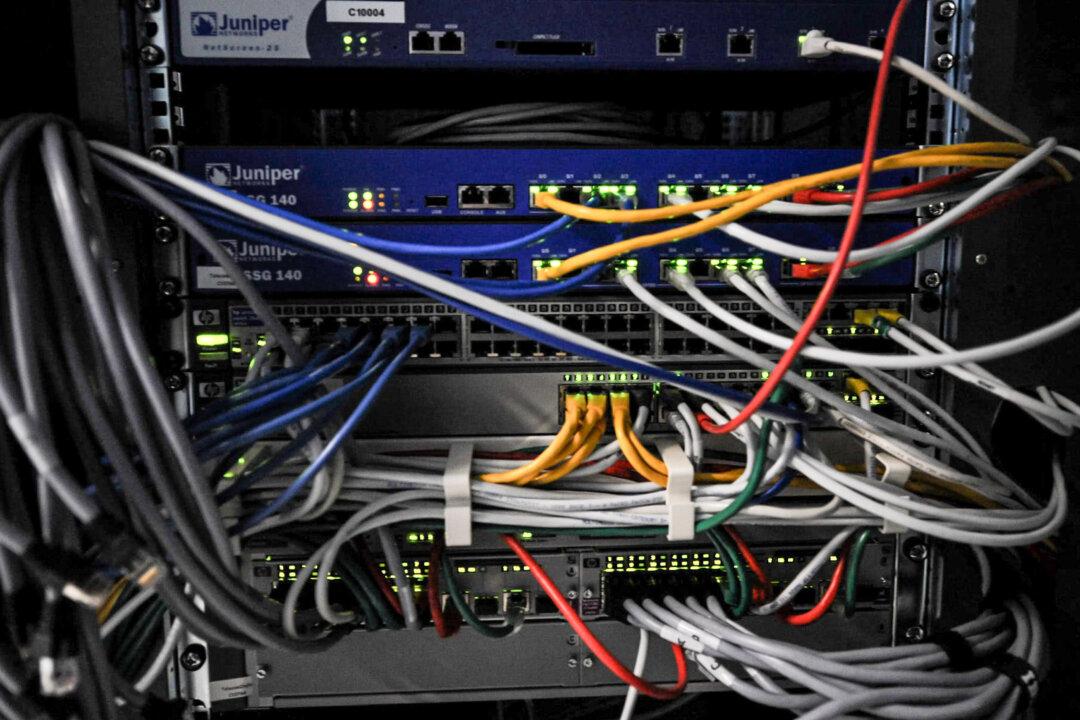

Patrick Hertzog/AFP via Getty Images