Commentary

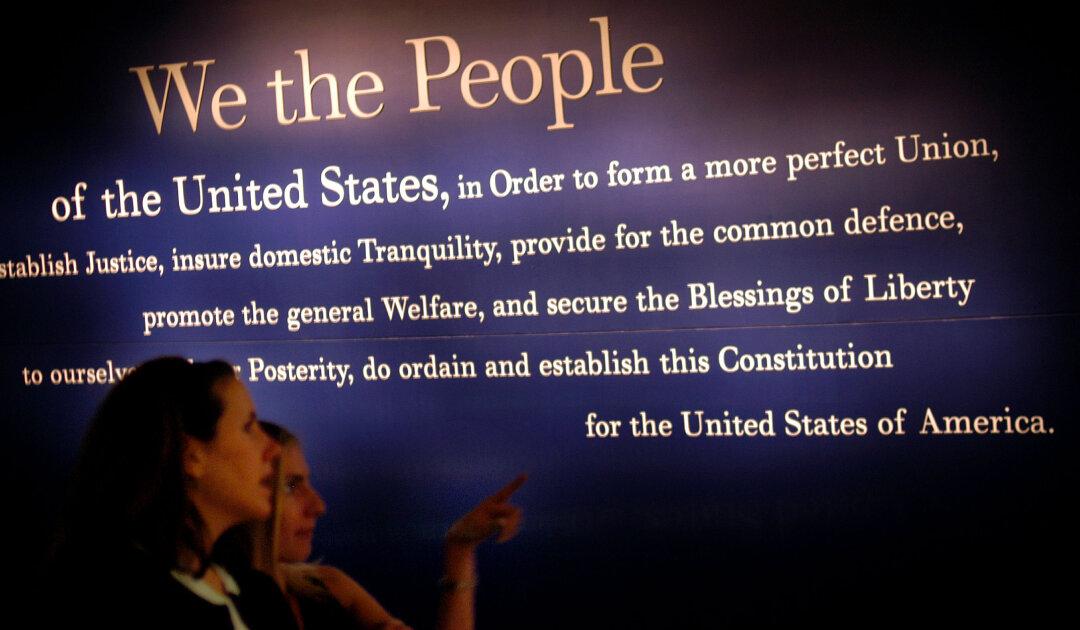

Americans traditionally have revered their Constitution—as they should, if only because of the astounding success the United States has enjoyed under its governance.

Americans traditionally have revered their Constitution—as they should, if only because of the astounding success the United States has enjoyed under its governance.