Commentary

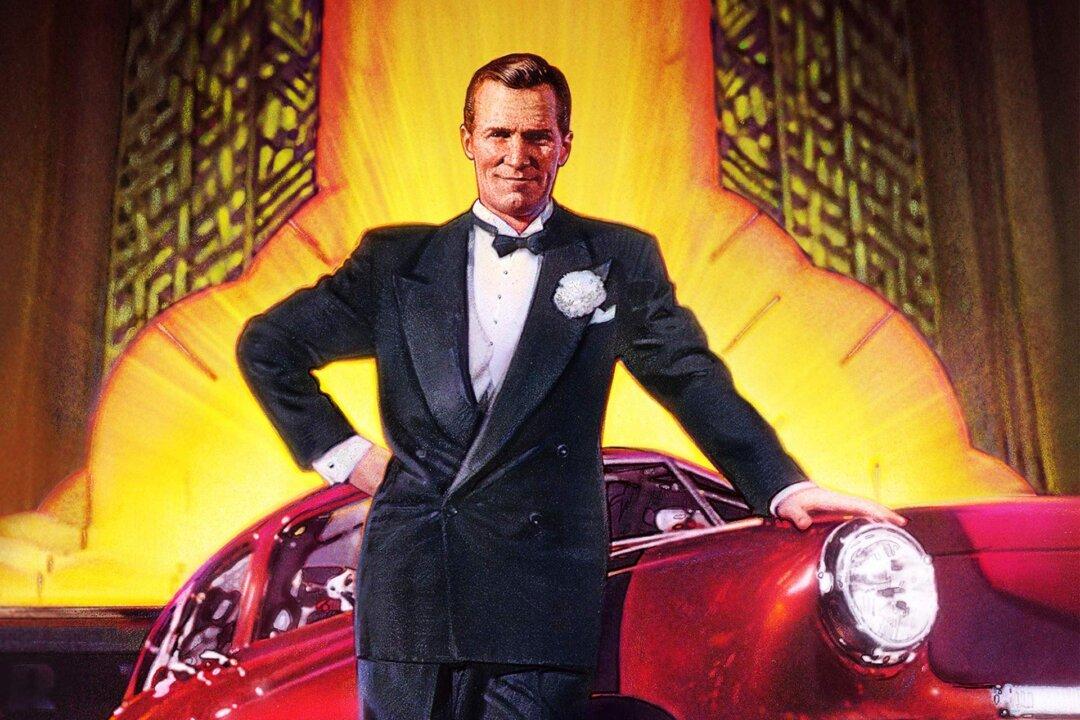

Imagine a situation in which a single industry, dominated by a coalition of producers, captures the regulatory apparatus and the politicians who fund it. They rig the system against would-be competitors, pushing buttons and pulling levers.