Commentary

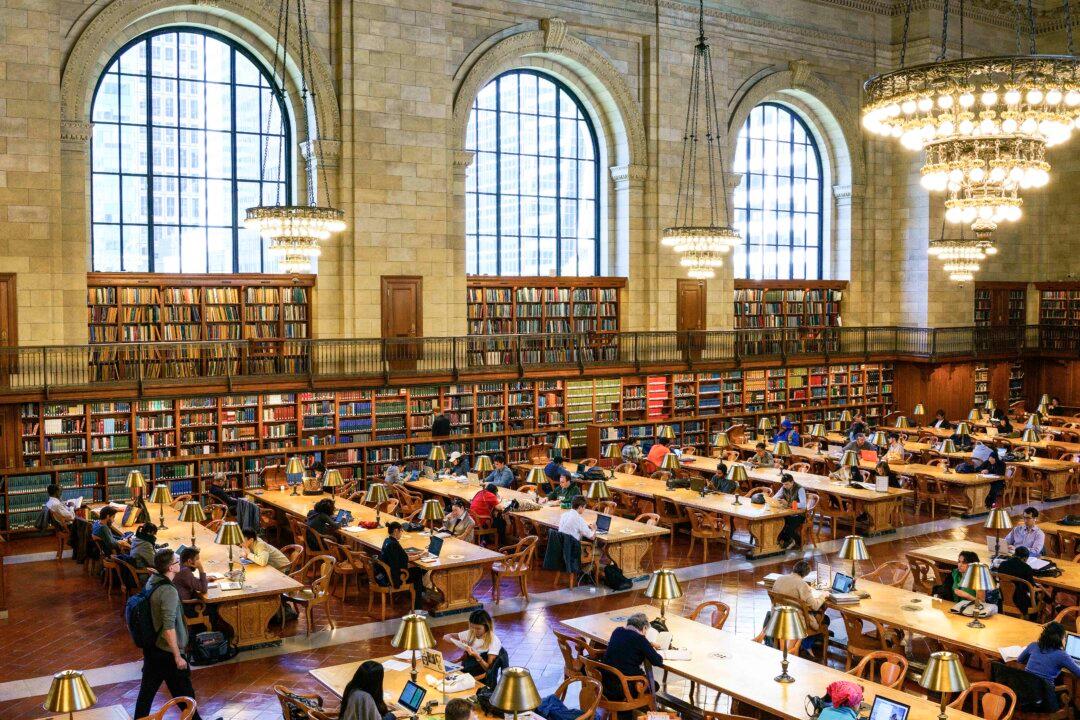

When I was a kid in New York City, the 96th Street library was a focal point of my life. Even though I was perpetually losing my library card and amassing fines for overdue books I didn’t want my parents to know about, it (as were the movie theaters on 86th) was my home away from home.